We are currently confronting an inflationary crisis, a banking crisis and a deepening crisis of poverty. These are not separate events. Rather, they all trace back to the glaring contrast between wealth and poverty, which was unabashedly on full display (yet again) in the month of March. While government programs of vital necessity to the poor were being rolled back, banks were bailed out to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve is managing inflation by raising interest rates and inducing further risks to an already fragile economy. While this will hurt banks and corporations, those who will be most harmed are poor and low-income households. As Rev. Cedar Monroe from rural Washington state reminds us about the bank bailouts, “we didn’t avert a new depression… For the poor, we are in the middle of one.”

This policy briefing focuses on inflation, the Silicon Valley Bank failure and continuing cuts to anti-poverty and social welfare programs. Together, they reveal how our society is organized to favor the wealthy. The only way to change this orientation is to organize the poor and shake up our national priorities.

1. Inflation and Interest Rates

The most recent report on consumer inflation shows that price increases are cooling: while prices are still going up, they’re not going up as fast as they were last year. In response to inflation, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates 9 times over the past year, from 0.25% to between 4.75-5% this month. Every time it raises these rates, the costs of lending go up, making home loans, auto loans, credit card borrowing and business lending more expensive. While banks and businesses are immediately impacted by having less access to cheap money, workers and households feel these impacts through layoffs and higher interest rates on their credit cards, mortgages and other loans.

For months, economists have been sounding the alarm that raising interest rates further will only do more harm to a precarious labor market, workers, and poor and low-income households. While this action on the part of the federal reserve may force prices down by restricting demand, it is applying the wrong tool to address the root causes of inflation itself, which were pandemic supply chain issues, the war in Ukraine, constricted labor supply and corporate price gouging. And this action will have devastating consequences.

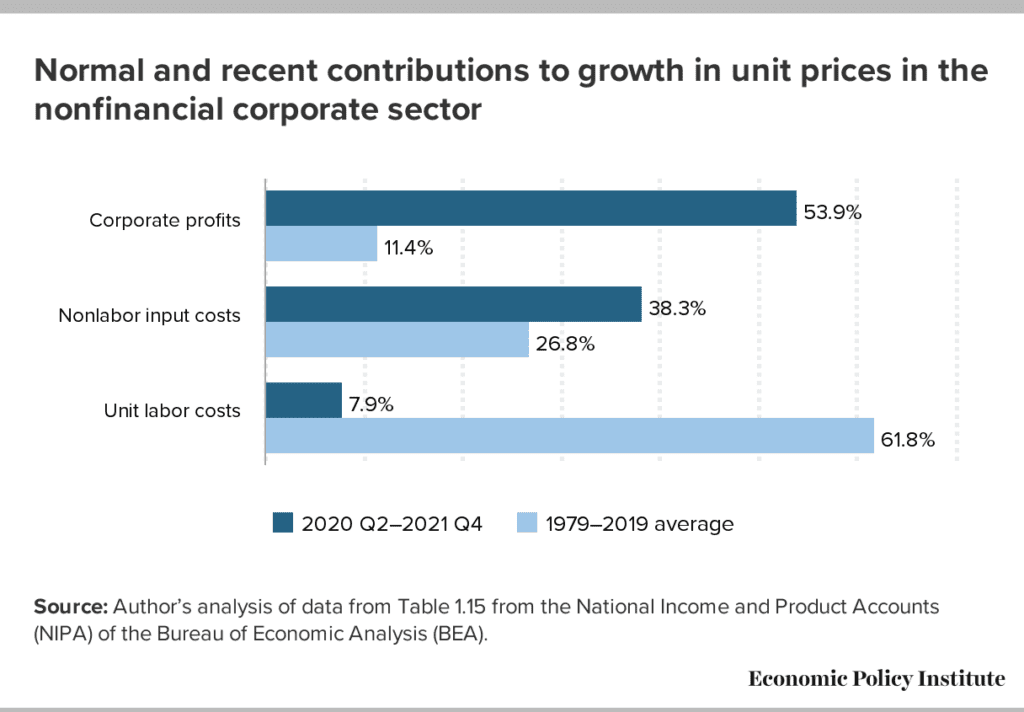

Instead, more attention should be paid to the influence of corporate profits on consumer prices. According to Josh Bivens, Director of Research at the Economic Policy Institute, In 2022, over half (53.9%) of the increases in prices was attributed to “fatter profit margins” enjoyed by corporations, while labor costs were only responsible for 8% of these increases. “This is not normal,” Bivens writes. “From 1979 to 2019, profits only contributed about 11% to price growth and labor costs over 60%.” More than higher wages or supply and demand asymmetries, it is corporations and banks that have increased consumer prices in the past year.

And as discussed below, corporate profits and rising interest rates played a key role in the Silicon Valley Bank crisis and the ongoing economic fallout.

2. Silicon Valley Bank and Why Banks Keep Getting Bailed Out

On March 10, 2023, the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed. SVB was a primary lender to Silicon Valley startups and venture capitalist firms that were heavily invested in the tech sector. By January 2023, it held over $200 billion in assets and was the 16th largest bank in the country. This is the second largest bank failure in US history. It was soon rescued by the Federal Reserve and US Treasury to prevent any further contagion in the broader financial system.

Other mid-size and smaller banks have, however, been rattled and are losing value: within hours of SVB’s collapse, Signature Bank, which was heavily invested in crypto, also failed. It was rescued by another, larger bank. A few days later, 11 of the largest US banks announced that they were injecting $30 billion into First Republic Bank to prevent its collapse. According to new research, another 186 banks are at risk of bank runs, for similar reasons as SVB.

Also in March, the European Credit Suisse bank lost 30% of its shares. Its biggest shareholder, the Saudi National Bank, refused to cover the bank’s losses. This prompted UBS, the largest private bank in the world, to step in and take over. While not directly related to SVB, this failure indicates a deeper instability in the global financial system.

SVB’s History and Investments

SVB was founded in 1983. Most of its clientele were venture capitalists, tech companies and start-ups that grew dramatically with the Silicon Valley boom. In fact, SVB funded half of US venture-based start ups. In 2021, these entities were flush with cash that they deposited with SVB. The bank, in turn, invested the bulk of those deposits in long-term government bonds. When SVB purchased those bonds, interest rates were close to zero.

As the Fed began to raise interest rates and the economy started slowing down in 2022, these companies’ access to easy money began drying up. SVB’s depositors began to draw out their cash to pay expenses, requiring SVB to turn in its bonds.

Bonds work like an IOU from the US government. You purchase the bond with a promise that the US government will buy it back from you, with interest, when it is fully matured (which can be in a matter of months or years). A low-interest bond will return the cost of its original purchase and small amounts of interest over time. A higher-interest bond will return the cost of its original purchase with a higher interest payment. When the Federal Reserve increased interest rates, the interest rates on bonds also went up. A two-year treasury bond has a current interest rate of close to 4%, while SVB’s bonds’ rate was about 0.2%. The only way SVB could turn in its bonds was at a loss of $1.8 billion.

When SVB tried to cover these losses by issuing new stock, its investors reacted strongly and pulled their investments. SVB stock plummeted and the bank lost $160 billion in value in just 24 hours. As their stock fell, depositors went to withdraw their accounts, leading to a classic bank run.

When it became clear that SVB was crashing, it was taken over by regulators. Massive amounts of money were made available, very quickly, to make sure wealthy investors and executives did not lose any of their money.

Connecting SVB’s Failure to the Inflationary Crisis

In 2021, the tech sector was drawing in hundreds of billions of dollars from venture capitalists, whose wealth was coming, directly or indirectly, from the Federal Reserve: between March and June 2020, the Fed pumped $3 trillion into financial institutions and corporations, to rescue the economy from the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic.

Back in 2020, Chairman Powell said he was willing to do whatever it took, for however long it took, to ward off a Great Depression. The Fed implemented several programs to ensure that banks kept financial markets flowing by lending and investing to companies and households.

As a result, stock prices shot up. Not only were stockholders’ confident that the Fed would not allow the stock market to tank, corporations were giving back billions of dollars to their shareholders in the form of stock buybacks. Corporate profits soared.

In 2022, the Fed began increasing interest rates to curb rising prices. This time, Powell said that there was no “painless” way to curb inflation, fully aware of the risks of recession, unemployment and further economic woes for financially insecure households. As the economy began to slow down, tech investors lost $7.4 trillion and more than 120,000 tech workers were laid off, precipitating the downfall of SVB.

Banking Deregulation and High-Risk Banking

One of the reasons why SVB could not pay all of its depositors was because, like many banks, it was involved in both commercial lending and investment banking: it used its depositors’ cash to speculate on stocks and bonds to increase its holdings and profits. This means it simply did not have adequate reserves or liquidity to withstand financial shocks, let alone return all of its depositors’ money all at once.

This was relatively new activity for SVB, which it primarily took up after the Dodd-Frank Act was effectively repealed in 2018.

Dodd-Frank is part of a long regulatory history dating back nearly 100 years. Before the 1929 stock market crash, commercial banks had become heavily invested in the stock market. Like SVB, they were using their customers’ deposits to buy stocks and bonds, both driving up stock prices and depleting their own cash reserves. This merger of commercial and investment banking activity is often cited as one of the leading causes of the 1929 stock market crash and Great Depression that followed.

As part of the New Deal, Pres. Roosevelt enacted the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, essentially forcing banks to choose between commercial lending and investment banking as their primary activity. Under the terms of the Act, only 10% of commercial banking resources could stem from securities and investments. The Act also allowed the Fed to regulate retail banks, encouraging banks to lend rather than invest, so as to increase commercial activity and grow the economy back from the Depression years.

Although it was constantly under political pressure, Glass-Steagall remained more or less in place for decades, until 1999 when its hallmark restrictions on merged banking activity were repealed by the Gramm-Leach-Bailey Act. Pres. Clinton signed this Act into law after he had already enacted the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act or welfare reform (1996), Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act (1996), the Omnibus Crime Bill (1994) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994). The full effects of these bills are apparent today in consolidated corporate power and the influence of Wall Street, the proliferation of low-wage work and widespread poverty, a hollowed out social safety net, punitive immigration system and mass incarceration.

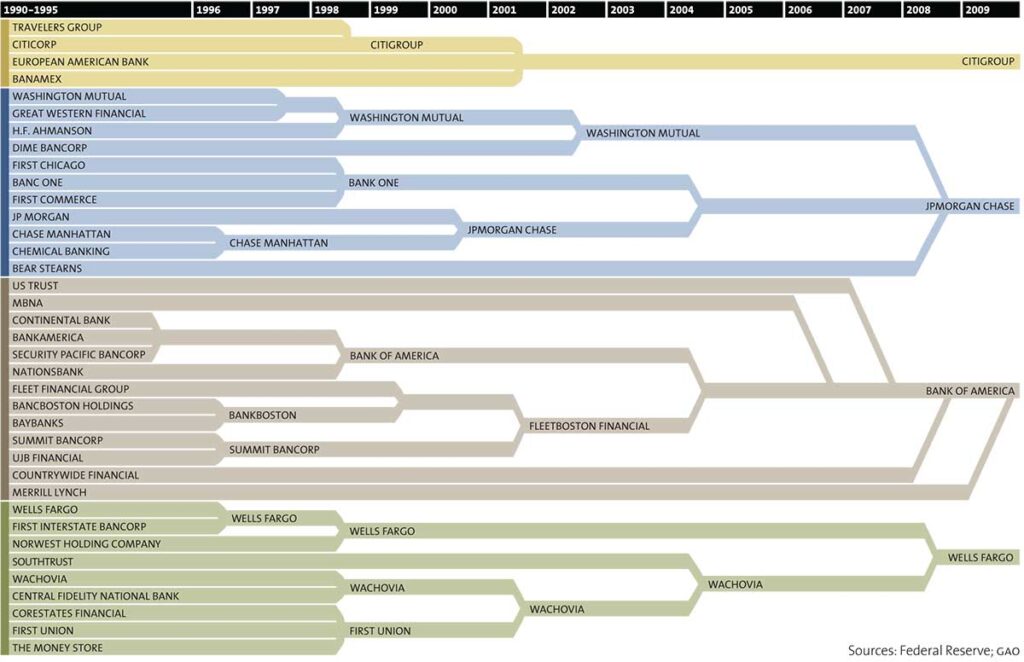

Once Glass-Steagall was effectively repealed, commercial banks began taking on risky investments to boost their profits, including speculative activity and high-risk lending that many believe led to the 2008 financial crisis. In doing so, some banks became “too big to fail,” as they acquired vast amounts of wealth through investments that were intricately woven through national and global financial systems.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Pres. Obama enacted Dodd-Frank to protect against this scale of systemic harm. Similar to Glass-Steagall, Dodd-Frank restricted how commercial banks could invest: it limited speculative and proprietary trading by banks and required them to have a certain amount of cash reserves on hand. In 2018, Pres. Trump rolled back these protections,in particular, as they applied to small and mid-size regional banks like SVB. In fact, SVB’s CEO lobbied to repeal these restrictions back in 2015.

3. The continuing assault on the poor: SNAP, Medicaid and More

It is important to contrast the response to SVB and the crisis facing the banks with the response to economic insecurity and the crisis facing the poor. Recall that before the pandemic, nearly 140 million people were poor or one emergency away from being poor, 87 million people were uninsured or underinsured, 8-11 million people were homeless or on the verge of becoming unhoused, millions of households could not afford their water and three people owned more wealth than half of the country. Health care was one of the most popular political issues, cutting across party lines.

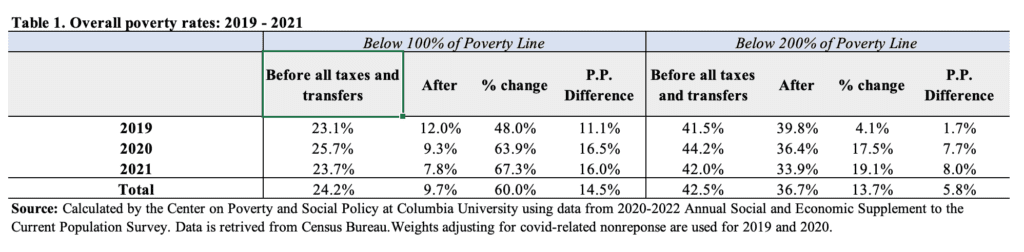

During the first two years of the pandemic, stimulus checks, expanded unemployment insurance, expansions to the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit, expansions to SNAP and Medicaid and moratoriums on evictions prevented pre-pandemic economic conditions from further deteriorating for millions of households. In fact, these programs kept more than 20 million people above the poverty line and the number of poor and low-income individuals fell from 140 million to 111 million in 2021.

According to experts at the Columbia Center for Poverty and Social Policy, this was almost entirely due to pandemic expansions to existing anti-poverty programs. When these programs were expanded in 2020 and 2021, the post-tax and transfer poverty and low-income rates were markedly lower.

Towards the end of 2021, while resources were still flowing to banks, financiers, corporations and big businesses, these anti-poverty policies and programs began to be clawed back:

Eviction protections: On August 26, 2021, the Supreme Court rejected the Biden Administration’s latest moratorium on evictions, putting 6-17 million people at risk of losing their housing. In its 8-page majority opinion, the Court ruled that the CDC exceeded its authority when it issued its public health-advised moratorium. Instead, it decided that Congress needed to take action to implement a moratorium, not the CDC. The moratoriums were subsequently lifted, even research showed they had been effective at decreasing both COVID-19 infections and deaths. The country’s largest real estate industry group spent tens of millions of dollars lobbying to end the moratorium.

Unemployment Insurance: While some Republican-led states had rolled back unemployment programs a few months before, the largest federal expansions to unemployment insurance ended on Labor Day, September 6, 2021. Again, these expansions – including higher benefit levels, expanded access for independent workers and people who could not work due to COVID-related reasons and increasing the number of weeks people could receive these benefits – were both long-overdue and effective, especially for low-income workers and households. They kept millions of people above the poverty line and boosted consumption, which was good for the economy as a whole. One of the strongest lobbies to end these expansions came from the US Chamber of Commerce, in a coordinated effort to push people back into precarious employment.

Expanded Child Tax Credit: In December 2021, over 35 million households with more than 60 million children received their last monthly payment under the expanded CTC. These payments had both reduced child poverty rates and racial inequities among poor children. As subsequent research showed, these payments were used to pay for rent, food, childcare and other necessities for the children in these households. They improved household mental health and emotional well-being and were a necessary addition to other critical public assistance. When the program was prematurely ended, gains were swiftly undone. By January 2022, child poverty rates went up five percentage points, to their highest levels since 2020. In just a few weeks, 3.7 million children fell below the poverty line, with the greatest losses experienced among Black and Latino children. These numbers and rates remained elevated throughout 2022.

Minimum Wage, Inflation and Interest Rates: Although consumer prices began increasing in the first few months of 2021, the Federal Reserve waited one full year to raise interest rates. Within this time, 25 states had also increased their minimum wage, but those increases were neutralized by inflation, job losses and the termination of pandemic assistance programs. By the end of 2022, monthly poverty rates were back to pre-pandemic levels.

SNAP and Medicaid: In March 2023, pandemic expansion to SNAP (food stamps) came to an end. For nearly two years, 42 million poor and low-income people had been receiving expanded benefits, on average $257 per month. Again, these pandemic expansions were overdue. Before the pandemic, SNAP benefits did not cover the average cost of a modestly priced meal in 96% of US counties. As of 2023, however, households across 32 states, Washington DC, Guam and the US Virgin Islands will lose anywhere from $90 to over $250 per month in food stamps. These cuts will inevitably lead to rise in hunger and food insecurity, especially as grocery prices have increased 10% over the past year.

Also in March, continuous Medicaid coverage established in 2020 will come to an end. An estimated 15 million people will lose their access to free and affordable health care.

Now, Republican members of Congress are pushing to make the Trump tax cuts from 2017 permanent, while insisting that government spending be reduced to 2022 levels. This could mean that in addition to these existing cuts, funding for food security programs, health care, public education, HeadStart, child care, housing assistance, climate research and other programs funded by non-discretionary spending could be cut back dramatically, anywhere from 9% to 100%. While this assault may be mediated to some extent by the Biden Administration – or the slim Democratic majority in the Senate – it also demands massive pressure from a united front of poor and low-income people pushing back against compromises that will harm anyone, any further.

Indeed, for decades, our politics and policies have been organized around the basic assumption that the rich will save the rest of us. When those policies fail, the poor are wrongly scapegoated and punished, but the assumption still stands. This is why there are 140 million poor and dispossessed people in this country, facing crisis after crisis, with fewer resources and institutions to rely on to meet their needs. If, however, these tens of millions of people were organized to take action together around their common needs – across race, issue, faith and geography – they could move our country in a fundamentally new direction, where all of our needs are met, our communities provided for and our climate restored.

This is the way forward, with and through the leadership of the poor.

Resources for further study and reading

- An Update on Inflation

- Fed hikes likely to cause a recession

- Economists on Fed’s interest rate hikes and impact

- Economic Policy Institute’s Director of Research Josh Bivens: On inflation and corporate profits

- SVB and Why Banks Keep Getting Bailed Out

- In These Times: Breakdown of SVB crisis

- Economist Adam Tooze: On the banking crisis and SVB

- SSRN research paper: Monetary Tightening and US Bank Fragility in 2023

- Wealth inequality in America visualized (2012)

- Mary Poppins Bank Run, Video Clip: Give me back my money!

- The Continuing Assault on the Poor

- US Census Bureau: Poverty in the United States, 2021 report

- Brookings Institute: Lessons from Expanded Unemployment Insurance

- National Employment Law Project: Expanded Unemployment Insurance reduced Poverty

- NYTimes: Reporting on Unemployment Benefits

- US Chamber of Commerce: Statement on Pandemic Unemployment Benefits

- Duke University Research on Impacts of Moratoria on Evictions and Utility Shut-offs during Pandemic

- US Supreme Court: Ruling on CDC Eviction Moratorium

- Center on Poverty and Social Policy: Research Roundup on CTC and Monthly Poverty Data

- Report on impacts of CTC: I Didn’t Have to Worry

- Coalition on Human Needs: Tracking Hardshop, SNAP Edition

- Urban Institute: SNAP Food Cost Gap

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Cuts to SNAP, 2023 and Medicaid Cliff