In our assessment of social movements in U.S. and world history, the Kairos Center has concluded that movements begin with the telling of untold stories. These stories start to break through the false narratives and myths that hold up unjust social, political and economic systems; and in telling their stories, those most impacted by those systems break through their own isolation and emerge as leaders in their communities, who can connect with emerging leaders, as they, too, find their voice. These stories relay more than the crushing details of their struggles. They contain also the lessons of those struggles and insights on how to organize to win.

As we have studied poor people’s organizing including the Abolitionist Movement, Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union and labor movement, civil rights movement, welfare rights organizing, homeless organizing, the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign and more, we have seen the power of these stories to shift the social consciousness and prepare the way for a new society to be born. This is why identifying leaders and lifting up their stories is part of the Kairos Center’s methodology for social transformation. Through truth commissions, hearings, cultural expression, audio-visual media, and social media, we collect and compile these stories to develop an exact and positive knowledge of the conditions that 140 million poor and dispossessed people are facing in the U.S. today and how they are organizing and responding to those conditions.

These stories are the bedrock of our policy work. They are present throughout the Souls of Poor Folk: Auditing America report and the Poor People’s Moral Budget: Everybody Has a Right to Live. They have been offered into the Congressional record through special orders, a Hearing on Poverty in front of the House Budget Committee in June 2019, and several other hearings in front of other House Committees.

One key testimony is from Sharon Lavigne of St. James, Louisiana, who testified in front of the Environment and Climate Change Subcommittee of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce on November 20, 2019. Sharon is a founder and organizer of Rise St. James, a grassroots, faith-based organization fighting for the removal of harmful petrochemicals in the land, air, water and bodies, of the people of St. James Parish. She grew up in St. James and has seen it disintegrate from a thriving community to a nightmare of industrial pollution.

St. James sits in the middle of Cancer Alley, the area between New Orleans and Baton Rouge where there are more than 100 petrochemical plants and refineries that are polluting the air, water and land00 , that has cancer rates up to 700 times the national average. In St. James Parish alone, there are 32 petrochemical plants. For its population of 21,000, that means there is one plant per every 656 residents, half of whom are black. Every household in this community has someone who has died of cancer. Sharon knows at least 30 people who have died from cancer in the past five years. At a recent Poor People’s Campaign mass meeting, candles were lit in remembrance of those who had died. Saying their names out loud took more than ten somber minutes.

Last fall, Sharon and others learned that Formosa Petrochemical was planning to build a multi-billion dollar plant in her district. It would produce plastic products and become one of the state’s largest emitters of ethylene oxide and benzene, both of which are known carcinogens. This is what prompted the formation of Rise St. James, to rise up and protect their homes and lands. Indeed, their generations-long ties to the land reach back to the days of slavery.

Just months ago, independent archeologists alerted state authorities to slave burial sites on the property where the Formosa plant is slated to be built. One of those sites was confirmed as a burial ground; another suspected site may have already been destroyed under previous ownership. Formosa knew of this and perhaps other burial grounds as early as July 2018. According to public records, a company representative discussed removing one possible burial site, if confirmed, with the Louisiana Attorney General because leaving the remains undisturbed would be a “difficult option” for the company.

Rise St. James is now working with the Center for Constitutional Rights to protect this connection to their ancestral history and prevent the further destruction of this hallowed ground. Rise St. James is also part of the Louisiana Poor People’s Campaign.

Read below for Sharon’s testimony in front of the House Subcommittee and see the video here.

Building a 100 Percent Clean Economy: The Challenges Facing Frontline Communities

Written Testimony by Sharon Lavigne

My name is Sharon Lavigne. I am the daughter of a Civil Rights Movement leader and I live in St. James Parish, Louisiana. When I was growing up, St. James was a vibrant place and I lived the American Dream as a little girl. But today, we’re living through a nightmare of industrial pollution and disease. In the 1960s, the first industrial plant came to St. James Parish. Many more followed. By 2017, I joined a community organization called HELP — the Humanitarian Enterprise of Loving People, HELP — where I learned about industrial pollution and its harmful effect on our environment and the health of people who live in my community.

In spring 2018, our Governor John Bel Edwards announced a $9.4 billion industrial factory proposed by Formosa Plastics wanted to locate in St. James Parish, a mile from the local public school and two miles from my home. While researching the project’s history, we found out that in 2014, the Parish Council changed the land use plan for the 5th district where I live from ‘residential’ to ‘residential/future industrial.’ Our residential neighborhood was suddenly deemed “future industrial” without our knowledge or consent.

The 5th district of St. James is already surrounded by industry and it is making us sick. Maybe you’ve seen the press coverage of “Cancer Alley,” where I live, which we’re now calling “Death Alley” because the health threats we face take so many forms. I have auto-immune hepatitis and aluminum in my body. My grandchildren have breathing problems, and when they are outside playing for any period of time, they develop rashes.

During the HELP meetings, I would ask what we could do to stop this plant from coming in to St. James. People would tell me there was nothing we could do to stop it. Once the Planning Commission votes yes on the project, the Parish Council follows them and you can’t do anything about it. I was told “There’s nothing you can do about it, Sharon, it’s a done deal”.

So I would come home after those meetings and cry. One day, I sat on my porch and I prayed. I talked to God and I said, “Do you want me to give up the land that you gave me?” He said no. I said, “Do you want me to give up the home that you gave me?” He said no. I said, “What do you want me to do?” He said I want you to fight.

That was the beginning of my fight to stop Formosa Plastics. I felt like we were already bombarded by enough industry in the 5th District, why should another chemical plant get to come here? I found out the Formosa plant isn’t just one plant, there are 14 plants within the planned facility. Fourteen! I didn’t know how to fight, didn’t know what to do, and I had never stood up to industry in my life. My first meeting I held was at my house, on a Saturday in October 2018. I had 10 people come – two of them have died this year. After the meeting, I went to an NAACP meeting in Baton Rouge at Southern University where they were talking about pollution and industry. I had a poster that I made, and I brought it with me. I explained to people what was going on, and people started giving me their cards and telling me they were going to help me.

The next meeting was in my garage with 20 people. That was when we decided to come up with a name for our group. We decided on Rise St. James. After that, we planned our first march in November of 2018, a Saturday. It was a small march. We couldn’t march on the highway because the Sunshine Bridge was closed for construction, so the police told us to march on the sidewalk. That march brought a lot of attention to the people in the 5th District. That was one of my first times speaking in public. After that first Rise St. James march, people from other parishes who live near industry saw us speaking. They asked if they could join Rise. Communities on both sides of the Mississippi River joined together. We’ve been growing ever since.

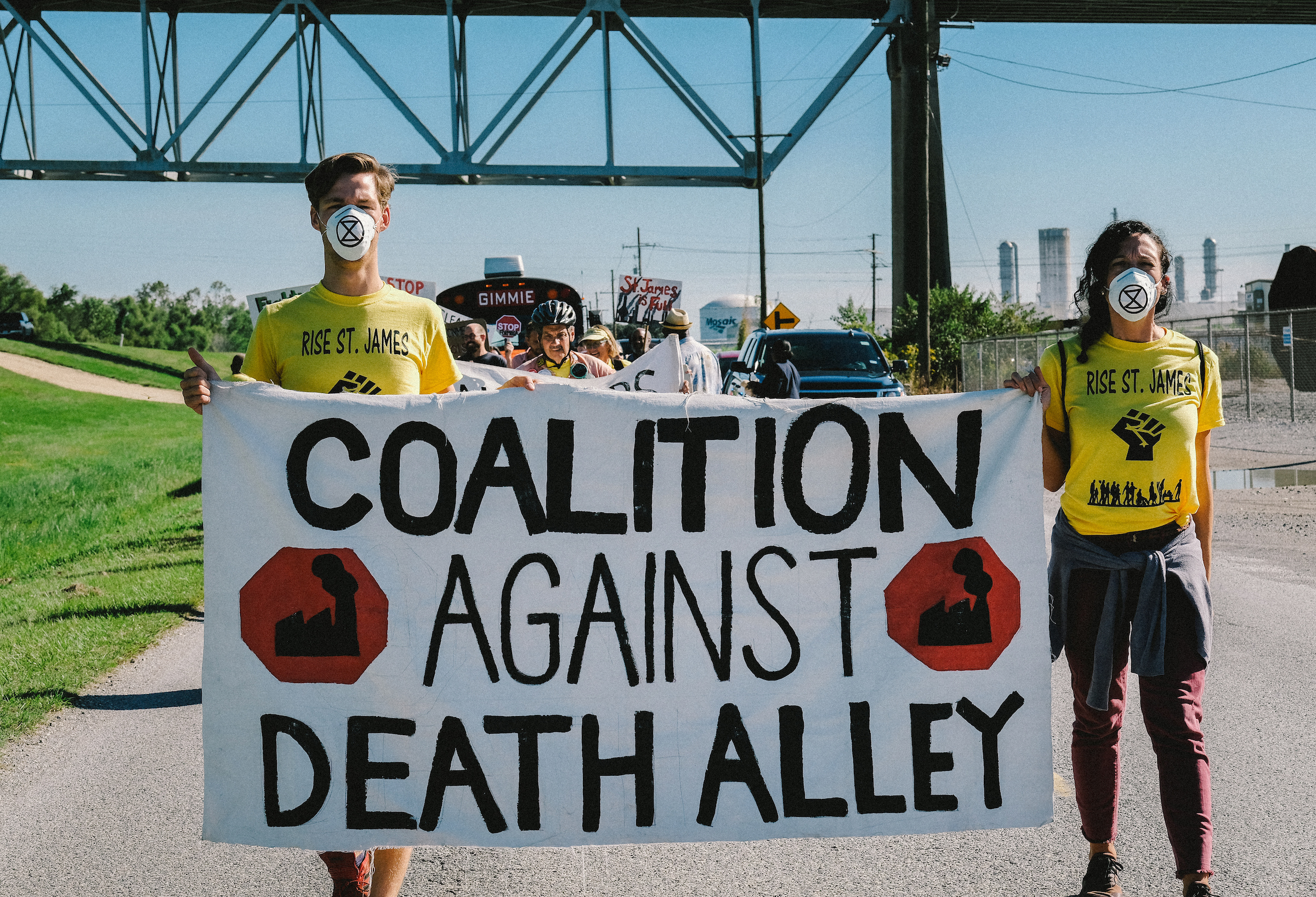

We formed a coalition called the Coalition Against Death Alley. As I said, we live in Cancer Alley but we changed our coalition name to the Coalition Against Death Alley because this exposure to more and more industrial pollution is a death sentence. We meet twice a month and we planned a successful five-day march to the Capitol, but the governor would not come out to speak with us.

We just had our second march with the CADA Coalition on October 16-30. This time it was a 13-day march and Reverend William Barber, a civil rights leader and founder of the Poor People’s Campaign, joined us. He said that what is happening in Cancer Alley is genocide, and the fossil fuel industry is poisoning us. They don’t want to drink the water that we are drinking and breathe the air that we’re breathing. They don’t live here.

Rev. Barber spoke on our behalf. This march brought national recognition and media attention, and it made a lot of people aware of what’s going on here. We plan to have another march in the spring of 2020 and we’ll keep marching until our community is protected.

We’ve already had one victory. We worked to block a $1.5 billion petrochemical plant called Wanhua from moving to St. James Parish and being built within a mile of our homes. We appealed the St. James Parish Planning Commission’s approval of Wanhua’s land use permit and we won. Wanhua withdrew its proposal and ended up pulling out.

But we need your help. Rise St. James is asking for a moratorium on the oil, gas, and petrochemical industry in our Parish. Every piece of plastic is made of fossil fuels and the fracking boom is driving a massive expansion of plastic. These new plastic plants poison our communities and deepen the plastic crisis. We want them to stop expanding. We’re working on that now. We want to protect our health, our homes, our land, and our future.

People in St. James need help from our elected officials. Our people are sick and they are dying. We had two residents from our community die recently. Last month, we had another member from Rise St. James pass. The memory of Geraldine will live on, she was a warrior, and the chemicals in our air kept her sick. Now we’re going to fight Formosa and we intend to win. Right now, they’re trying to get their air permit; we’re going to stop them. They’re coming in here to finish killing us. We’re already sick. If they come into St. James, they will be doubling the pollution in the air we breathe. Their emissions will double what local factories are already emitting.

These emissions include ethylene oxide, a toxic chemical that causes cancer like non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia, and breast cancer. Formosa’s plant would be the third largest emitter of ethylene oxide in the country. It would increase levels of this toxic substance in St. James many, many times over. I retired early from teaching on October 3, 2019. I wanted to work a year or two more, but God put this fight in me to Stop Formosa and any other chemical plant that comes to St. James. I am here because of the calling of God. I want to stop any and every industry that is coming to harm the health of the people in my community. God wouldn’t have put this fight on me if he didn’t have a plan. I invite all of you to come to St. James and see it for yourself. The civil rights struggle that my parents fought for continues today and we fight for our survival against industrial polluters.