A Response to Dr. Anantanand Rambachan’s Book, A Hindu Theology of Liberation – Not-Two is Not One

Below are remarks from Shailly Gupta Barnes at a recent panel on Dr. Anantanand Rambachan’s book, A Hindu Theology of Liberation – Not-Two is Not One. Also on the panel were Dr. Cornell West, Rev. Dr. Serene Jones, and Rev. Joshua Samuel, all of Union Theological Seminary. The panel was moderated by Union’s Dr. John J. Thatamanil.

Thank you

I’d like to thank Dr. Thatamanil for arranging this evening. As a Hindu and someone who has, for the past 10 years and more, been working with and for the poor and dispossessed, the question of a Hindu liberation theology is not just pressing; it is what grounds me in this long struggle towards dharma and justice in the world. So thank you for creating the space for this conversation here, at Union, where Pres. Jones, the faculty and staff and, above all, the student body continue to enrich a long history of liberative traditions by engaging in today’s radical times.

And, Dr. Rambachan, my profound thanks to you, for this contribution to a Hindu theology of liberation. Your work is a significant resource that will help shape our understanding of how we live and act in the world. This is especially true as the economic, political, social and spiritual crises that we are facing continue to deepen; and as the need for resources to draw from and know that we struggle not in vain, but out of a legitimate and moral imperative, increases.

Introduction

I work here at Union at the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights and Social Justice and the Poverty Initiative. Our mission is to draw on the power of religions and human rights to advance transformative social movements for human dignity. Our history goes back over two decades of movement building in the U.S. and world. We are working now to catalyze a new Poor People’s Campaign in this country, drawing on the legacy and vision of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, which brought together the poor and dispossessed across race, issue and geography, to struggle for their common economic rights and basic needs. This new Poor People’s Campaign is, and must be, grounded in today’s struggles for housing, health care, education, decent jobs, clean water, and peace; and against militarism, economic exploitation and inequality, police brutality, racism and other systemic oppressions.

Before the Kairos Center, I was part of the legal team that fought for – and won – waste pickers’ rights to livelihood in the Constitutional Court of Colombia, in a decision that basically translated the preferential option for the poor into waste management policy. Before that I spent 2 years living in a Sufi (Muslim) rural farming village in Niger as a Peace Corps Volunteer.

All of these experiences, but especially those of the past 7-8 years here at Union and as part of a broader effort to build a social movement to end poverty, led by the poor, have compelled me to revisit the religion and theology that I was raised with.

A Hindu Theology

I was raised in a Hindu-Jain family in Chicago, where the main lessons that informed my life were of dedication and detachment. This is a common interpretation of dharma and karma, that is, to work hard, to do your best at everything you do, and to remain detached from the results of those actions, because those are far beyond our control.

This way to live my life was fine for many years. As a student and lawyer, it helped to shape my work ethic and inspired me to act well in the world. Yet, once I became enmeshed in struggles for rights and dignity and realized what I – and the hundreds of community and religious leaders I’ve met over these years – are up against, this theology was profoundly inadequate. We are facing an array of forces that has deviously turned us against each other and against ourselves, forces that make us believe that we are the source of our problems, rather than the structures and systems that tell us: only half of you deserved to not be poor, the other half must wait until that first half is settled; if you’ve been forced to move or you’ve lost your job, you don’t deserve to have a house; if you can’t pay for water, you’ll not only have your water shut off, you will also lose your home and your children; and even if you have a job, you may need to pool your food stamps with your co-workers to pay for lunch.

There was no way that this theology of dedication and detachment could confront these forces! These forces are willing to shut down hospitals that aren’t making enough money and poison communities with incinerators, oil spills and toxins in our waters. This theology didn’t stand a chance in the face of such evil, in part because it did not take sides. Indeed, the notion of detachment, especially detachment from the results of your actions, facilitated a withdrawal from the world. This is true even though service and good works remain an important tenet of Hindu life and culture. And it had this effect because the focus of this theology was always the individual: it understood that transforming the individual was the key to transforming society. It therefore encouraged a relentless self-journey and addressed individual failures, rather than systemic ones, and stopped short of the capacity to take on adharma, or structural injustice, in the world.

This was not a failing of my parents, who gave me everything they had and more. They raised me to be a conscientious person, to think of others and act for the common good, as they themselves have. This was not even a failing of this theology per se. Dedication and detachment are not, of themselves, wrong, but they are also insufficient to confront the forces that we – and the poor and dispossessed of the world – face today.

A Hindu Theology of Liberation

The analysis that Dr. Rambachan develops in his book – and the careful exegesis of Hindu scripture – brings Hinduism (and specifically Advaita) back to the world, back to this world, and is an important contribution in confronting the prevailing Hindu theology of dedication and detachment.

Dr. Rambachan writes, “too much energy has been expended in Hinduism in establishing the so-called unreality of the world and too little on seeing the world as a celebrative expression of brahman’s fullness….” By contesting the dominant interpretation, he returns us to an examination of the reality of this world and encourages us to respond to it with our guiding principle of oneness and unity with the divine. This means denouncing any assumptions of the inevitability or permanence of inequality and exploitation as anathema to the inherent nature of brahman.

Just as important, he honors this call to be “more self-critical and less defensive, to hold our traditions accountable to their highest teachings,” as an act of devotion and love of this tradition. With the predominance of Hindu nationalism in India and its corrosive effects there and here, and also as people of faith, we Hindus must take seriously our cultural resources and question how they are used to maintain structures and systems of injustice.

This is not an issue just of India and Hindus only. Very close to home, we’ve seen this in recent ads with Donald Trump seated on a lotus leaf, as if he were a Hindu deity. These were sponsored by Indians, Hindus, here in the U.S. in support of a candidate who is publicly sowing racial division and inciting violence.

I have had to take this call to heart since becoming involved in this work of building a movement to end poverty. Over these past several years I have begun to see myself not in service of others, but in a community of struggle: fighting alongside others for their needs as well as mine and my family’s, and understanding that our security and dignity are deeply tied to the fate of the most vulnerable in our society. With this understanding, I’ve started to revisit some of the stories, myths, and scriptures that I was raised with, with new purpose and perspective. I have found that there are deep cultural resources within our Hindu tradition that offer insight and encouragement to social struggles happening today. These resources can, in fact, respond to the prevailing theology of dedication and detachment by offering a direction, strength, and moral legitimacy that we desperately need in the face of forces that will turn us against ourselves. They also indicate that, in its long history, there have been alternative interpretations of Hinduism and it is our responsibility to reveal that history and connect it to today’s context.

For example, the myth of the Samudra Manthan (the Churning of the Cosmic Ocean) denounces the hoarding of our most precious, life-giving resources, and provides a powerful source to draw on in this time of unprecedented wealth and resource inequality.

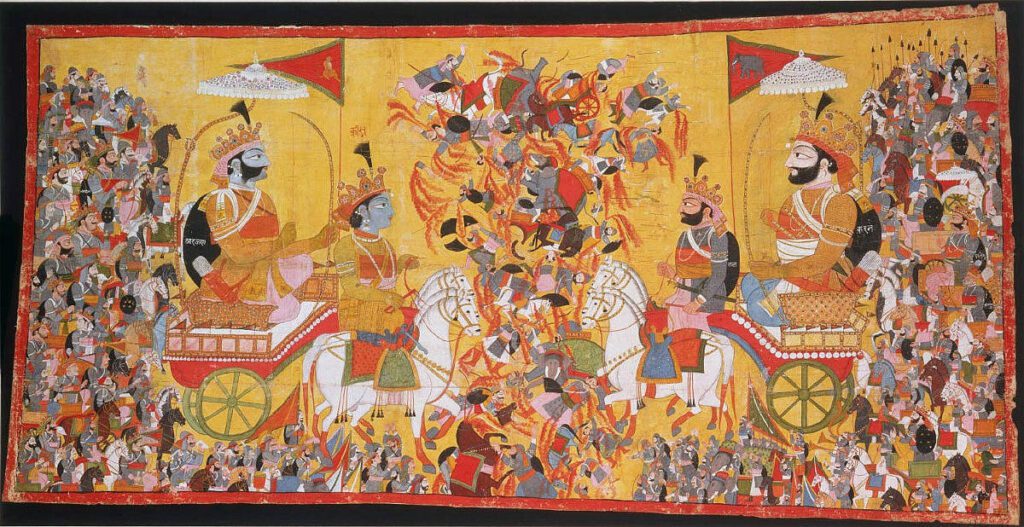

And, there is so much to draw from in the Gita, which is, above all, a call to action set in the context of an epic war. Many of the more common interpretations of the Gita turn this war into an internal and personal war of the ego, but the context of a legitimate war is important to revealing the liberative theology therein. Notably, in this war, Krishna, God, is not neutral: Krishna fights on the side of those who have lost everything, and against those who have perpetrated this injustice.

In fact, in Chapter 4, verses 7-8, Krishna tells Arjuna, an embattled warrior, that “whenever righteousness is on the decline, the unrighteousness [immoral] is in the ascendant, then I am reborn. For the protection of the virtuous, for the removal of the evil-doers, and for establishing Dharma (righteousness) on a firm footing, I am born from age to age.“

What he says is that God not only intervenes in this world, but that God intervenes for a specific purpose – to protect the virtuous, remove evil, and establish dharma and justice on firm footing. This is not a disinterested or detached Krishna. On the contrary, this God loves the world so much, that he is re-born from age to age to join those in struggles against injustice and to ensure that justice reigns, or until, as some of our friends and colleagues might say, God’s will is done and kingdom come, on earth as it is in heaven.

In this kernel of a Hindu theology of liberation, reincarnation is transformed into a social phenomenon: What is reborn is not the individual soul, but the continuation of a struggle for dharma started long ago and passed down from generation to generation – generations that have battled against unjust and oppressive regimes, systems, and structures. This is what connects us from past to present, this epic struggle for justice and truth. And this struggle is what Krishna calls us to, compelling us to join him on that battlefield, knowing we have the power and legitimacy of God on our side.

This, to me, is the task of a Hindu Liberation Theology: claiming our right, responsibility and agency as Hindus today – and with our relationship to struggles past – to engage deeply in the struggles for dharma breaking out in this country and elsewhere, as Krishna does. This theology is fighting for the world to be what it must be to honor the brahman, the divinity, which it is. Importantly, this theology is not only for Hindus or Indians or the Indian diaspora: It is for all those who struggle and fight against inequality, oppression and injustice, because we need all the resources we have to counter the forces we are up against.