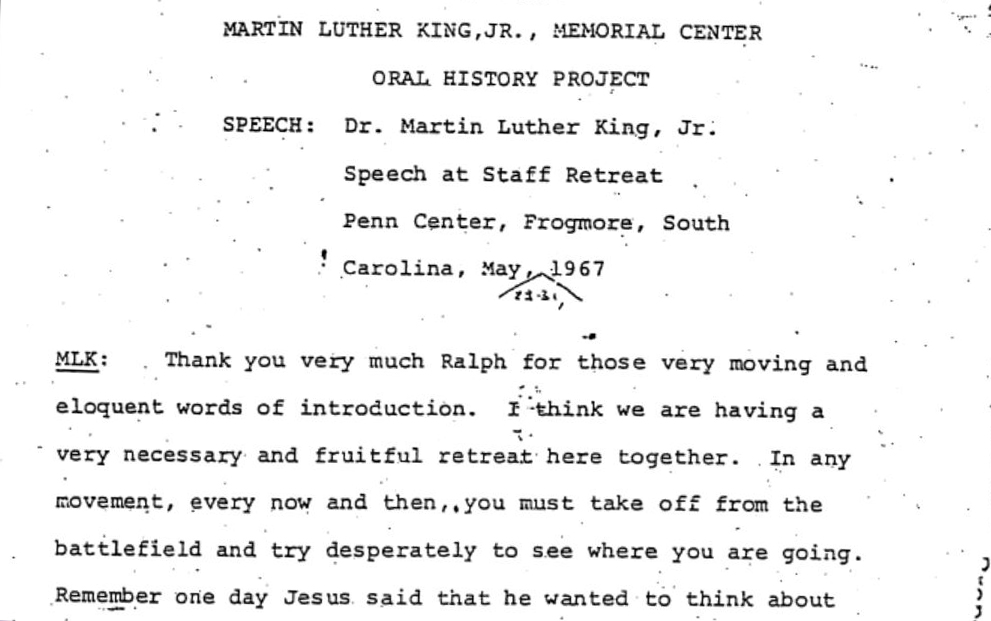

During the last few days of May 1967, fifty years ago this week, the staff of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) gathered for a planning retreat at the Penn Center in Frogmore, South Carolina. They were at a turning point. In just over a decade they had helped lead a movement to overturn racial laws and customs assumed to be immoveable. Those legislative victories came at a high price. Activists and conscientious citizens had been murdered. Jobs had been lost. Organizers worked to the point of exhaustion, sacrificing time with family. But for many black Americans the gains of civil rights had not changed their economic wellbeing. In some sectors, such as cotton farming, where mechanization had rapidly displaced most jobs, poverty actually increased in the 1960s. And the ending of legalized segregation had not dampened racism. There was much more work to be done. The staff came together in Frogmore to consider the past period and plan for the next.

Two months earlier, on April 4, 1967, Dr. King had made public his call to end the war in Vietnam. He linked the war to the violence of racism and poverty, saying that a national “revolution of values” would be necessary to move from a “thing-oriented society” to a “person-oriented society.” The response to his call was swift and decidedly negative. Media, elected officials and established civil rights leaders accused King of overstepping his realm of authority and betraying the interests of African Americans. This experience yielded an important lesson for King. Those who had been persuaded to join the struggle for civil rights quickly became sharp opponents when King addressed poverty and war.

And so when the SCLC staff was together at the Penn Center, King, as president of the SCLC, shared his reflections on where they had been, where they were going, and what would be required of the leadership of the movement in this new period. He began by saying, “We have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights.” Their past work had been part of a reform movement and the demands of the coming era must be met with a revolutionary movement that would require “a radical redistribution of economic and political power.” King goes on to explain that as difficult as the past period was, the coming period would be filled with greater challenges and fiercer opponents. It would require stronger, broader and more sophisticated movement leadership. They would need clearer, more revolutionary strategy. He describes this challenge politically and theologically, calling the SCLC staff to be willing to take up this challenge as Jesus took up the cross, bearing its costs — popularity, economic security and physical safety.

While King scholars sometimes cite the speech’s political and theological content, the text as a whole is unpublished. Below are five excerpts that give insight into King’s assessment of how the SCLC’s work would need to develop a new political strategy. Each passage demonstrates that he understood this transformation and their role as movement leaders in biblical and theological terms. And each is as relevant today as it was fifty years ago.

Now, when we see that there must be a radical redistribution of economic and political power, then we see that for the last twelve years we have been in a reform movement. We were seeking to reform certain conditions in the house of our nation because the nation wasn’t living up to the very rules of the house that it has prescribed in the Constitution. Then after Selma and the Voting Rights Bill, we moved into a new era, which must be an era of revolution. I think we must see the great distinction between a reform movement and a revolutionary movement. Now we are called upon to raise some questions about the house itself. Now we are in a situation where we must ask the house to change its rules, because the rules themselves don’t go far enough. In short, we have moved into an era where we are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society. We are still called upon to give aid to the beggar who finds himself in misery and agony on life’s highway. But one day, we must ask the question of whether an edifice which produces beggars must not be restructured and refurbished. That is where we are now. Now this means a revolution of values and other things. (p.8-9)

We must see now that the evils of racism, economic exploitation and militarism are all tied together. And you can’t get rid of one without getting rid of the other. Jesus confronted this problem of the inter-relatedness of evil one day, or rather it was one night. A big-shot came to him and he asked Jesus a question, what shall I do to be saved? Jesus didn’t get bogged down in a specific evil. He looked at Nicodemus, and he didn’t say now Nicodemus you must not drink liquor. He didn’t say Nicodemus you must not commit adultery. He didn’t say Nicodemus you must not lie. He didn’t say Nicodemus you must not steal. He said, Nicodemus you must be born again. In other words Nicodemus, the whole structure of your life must be changed…Now this is what we are dealing with in America. Somebody must say to America, America if you have contempt for life, if you exploit human beings by seeing them as less than human, if you will treat human beings as a means to an end, you thingafy those human beings. And if you will thingafy persons, you will exploit them economically. And if you will exploit persons economically, you will abuse your military power to protect your economic investments and your economic exploitations. So what America must be told today is that she must be born again. The whole structure of American life must be changed. (p. 9-10. There is a version of this section in the SCLC Convention speech King would give in August, 1967.)

So Jesus says love. When he says it he means it. Love is not meekness without muscle. Love is not sentimentality without spine. Love is not a tender heart without a tough mind. While it is none of that, it does mean caring. Love means going to any length to restore the broken community. Love means going the second mile to restore the broken community. Love means turning the other cheek to restore the broken community. And this is all the cross means to me…The cross is the revelation of the extent to which God was willing to go in order to restore broken humanity. And the Holy Spirit is nothing but a symbol of the continuing community creation reality (sic) moving through history. This is what we are called to do. (p. 27-8)

The cross is something that you bear and ultimately that you die on. The cross may mean the death of your popularity. It may mean the death of your bridge to the White House. It may mean the death of a foundation grant. It may cut your budget down a little, but take up your cross and bear it. And that is the way I have decided to go. (p. 31-2)