Fifty years ago, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. shared with the press that the SCLC would initiate what would come to be called the Poor People’s Campaign.

Across 1967 King and other leaders assessed the successes and limitations of the landmark victories of the past decade. King insisted that the triple evils of poverty, racism and militarism persisted because solving them would take a revolution of values and the transformation of society. He argued that the SCLC must shift their leadership from a civil rights movement to the building of a human rights movement, and from a reform movement to a revolutionary movement. In staff retreats, public speeches like Beyond Vietnam, and other writings, King put forward an increasingly clear assessment that, as he said at the announcement of the Campaign, “America is at a crossroads of history, and it is critically important for us, as a nation and a society, to choose a new path and move upon it with resolution and courage.”((Martin Luther King, Jr., “Press Conference on Washington Campaign” (Ebenezer Baptist Church, Atlanta, GA, December 4, 1967), King Speeches, Series 3, Box 13, King Center Archives., 2.))

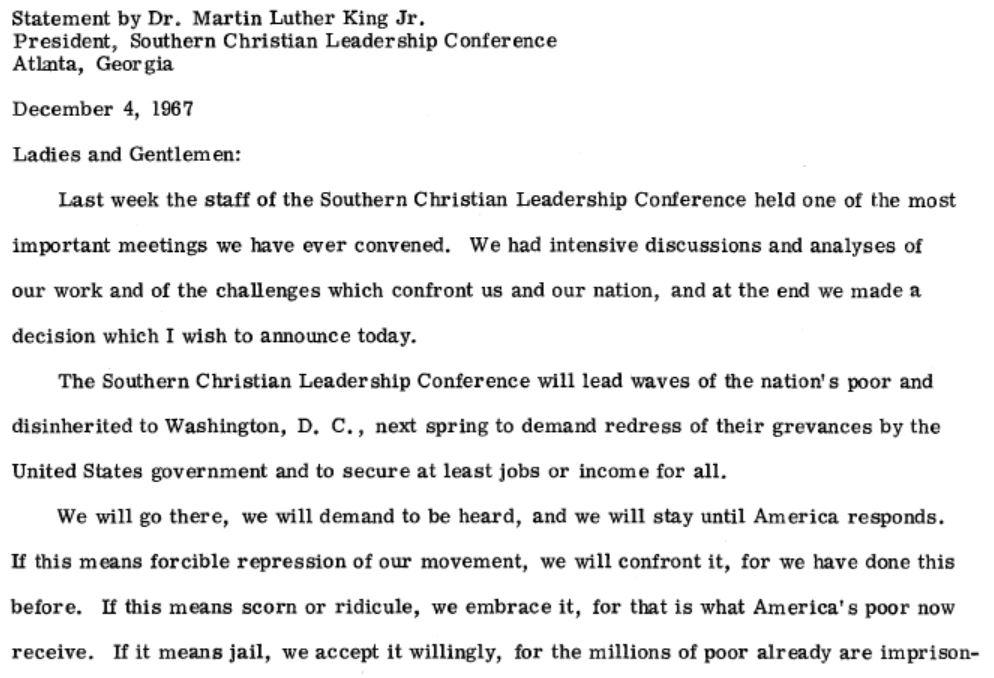

As the result of these discussions, on December 4, 1967, King and the SCLC announced,

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) will lead waves of the nation’s poor and disinherited to Washington, D. C., next spring to demand redress of their grievances by the United States government and to secure at least jobs or income for all.((Ibid., 1.))

This direction was controversial even among King’s closest lieutenants, who agreed to support the Campaign only after much debate. There was even less understanding from media, established civil rights institutions and elected officials. The SCLC anticipated and planned to confront “forcible repression”:

If [the Campaign] means scorn or ridicule, we embrace it, for that is what America’s poor now receive. If it means jail, we accept it willingly, for the millions of poor already are imprisoned by exploitation and discrimination. But we hope, with growing confidence, that our campaign in Washington will receive at first a sympathetic understanding across our nation, followed by dramatic expansion of nonviolent demonstrations in Washington and simultaneous protests elsewhere. In short, we will be petitioning our government for specific reforms, and we intend to build militant nonviolent actions until that government moves against poverty.((Ibid., 1.))

The “Washington Campaign” (as it was initially called) would be different from past campaigns not only in its focus on poverty, but in its inclusion of the poor across racial and ethnic lines. As planned from the start, the Campaign would include “representatives of the millions of non-Negro poor—Indians, Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Appalachians, and others.”((Ibid., 4.)) This broader inclusion of the poor was an important part of the shift from the assimilation of southern blacks in the existing economy—what King privately called “integration into a burning house”—to a transformation of the entire economy.((Harry Belafonte and Michael Shnayerson, My Song: A Memoir (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011).)) And this broader leadership would be particularly important, as many of the SCLC’s previous partners in the campaigns of the Civil Rights Movement would turn away from a campaign led by the poor and in opposition to the Vietnam War.

Soon after the announcement of the Poor People’s Campaign, King began to convene leaders from among the poor across racial, ethnic and geographic lines. These new partners—including poor whites, leaders from the welfare rights movement, the migrant labor movement, Native rights and Mexican American land rights organizing—would assemble in March 1968 to create a Committee of 100 for the Poor People’s Campaign, and to begin organizing the 6,000 multi-racial poor people who would come from nearly every state in the U.S. to occupy Washington D.C. that spring.

The Campaign would focus on influencing decision-makers in Washington, but this was understood to be an initial action that would begin to develop the leadership and direction for a larger movement for human rights:

The true responsibility for the existence of these deplorable conditions lies ultimately with the larger society, and much of the immediate responsibility for removing the injustices can be laid directly at the door of the federal government.((Ibid., 3.))

And a Campaign led by the poor would reveal the inseparability of the triple evils of racism, poverty and war:

Poor people who are treated with derision and abuse by an economic system soon conclude with elementary logic that they have no rational interest in killing people 12,000 miles away in the name of defending that system.((Ibid., 4.))

Where the roots of social problems are shared they must be attacked as such, uprooting the entire tree rather than attacking individual leaves and branches.

In the Campaign announcement, King said,

In a sense, we are already at war with and among ourselves. Affluent Americans are locked into suburbs of physical comfort and mental insecurity; poor Americans are locked inside ghettoes of material privation and spiritual debilitation; and all of us can almost feel the presence of a kind of social insanity which could lead to national ruin. Consider, for example, the spectacle of cities burning while the national government speaks of repression instead of rehabilitation. Or think of children starving in Mississippi while prosperous farmers are rewarded for not producing food. Or Negro mothers leaving children in tenements to work in neighborhoods where people of color can not live. Or the awesome bombardment, already greater than the munitions we exploded in World War II, against a small Asian land, while political brokers de-escalate and very nearly disarm a timid action against poverty. Or a nation gorged on money while millions of its citizens are denied a good education, adequate health services, decent housing, meaningful employment, and even respect, and are then told to be responsible.((Ibid., 2.))

Just before his death, King was asked whether he was getting away from his Christian roots and moving into “radical class politics.” He replied that the Poor People’s Campaign was the “most moral movement” and exactly what the Gospel called us to do.((Jose Yglesias, “Dr. King’s March on Washington, Part II,” New York Times Magazine, March 31, 1968.)) And he believed that while the government would not take real action to end poverty until forced to do so by direct and dramatic confrontation, the majority of the nation—”all Americans of goodwill”—would be moved by the actions of the poor and join them in the demand for a society based on human rights, “to move our nation and our government on a new course of social, economic, and political reform.”((King, Jr., “Press Conference on Washington Campaign,” 4.))

[aesop_image img=”https://kairoscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/PPCDec4.jpg” alt=”We Are Here: A Poor People’s Call for Moral Revival” align=”left” lightbox=”on” caption=”Join us on December 4, 2017 in Washington, D.C. for the launch of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

This year, on December 4, 2017—the fiftieth anniversary of the announcement of the first Poor People’s Campaign—a growing and diverse leadership will come together in Washington, D.C. to announce the launch of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. The effort is co-chaired by Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II of Repairers of the Breach and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis of the Kairos Center and is being taken up by a broad leadership of organizations, denominations and individuals on the many front lines of poverty. Together, we are responding to these times of profound crisis by becoming a nationwide, multi-racial campaign to call the nation to take dramatic steps to address the evils of racism, poverty, the war economy and environmental destruction. Our leadership comes from those of us who are struggling for our rights and the rights of our families to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, alongside national religious and thought leaders.

We are emerging in the spirit of the fusion movements of U.S. history, including the Poor People’s Campaign. And like King’s December 4, 1967 call, the moral questions we face put us at the crossroads of history, with deadly poverty in the midst of unprecedented abundance, entrenched racism, an astronomical war budget and irreversible environmental devastation. Only together can we call forward a movement capable of the “revolution of values” and “radical transformation of economic and political power” King knew would be required to transform society and meet the imperatives of the Gospel to love and serve the children of God and all of God’s creation.((Martin Luther King, Jr., “‘A Time to Break Silence,’ Speech at Riverside Church, April 4, 1967,” in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James M. Washington (San Francisco: HarperOne, 1991); Martin Luther King, Jr., “To Charter Our Course for the Future” (Frogmore, SC, May 22, 1967), 9, King Speeches, Series 3, Box #13, King Center Archives.))