I have been blessed these last few months. Blessed to feel inspired, curious, connected, and so grateful for — of all things — a course on the movement to end slavery. Offered by the University of the Poor, two classes of about 20 folks each read articles and book chapters, watched videos and listened to podcasts, then met online for 10 weeks, just an hour & a half a week, to dig into the history. In some ways it was just a survey course on a particular historical time period — roughly 1820–1865 — but our context, our teachers, our texts, our students, our focus, and our ambition made it entirely unique.

A few years ago, while we were still in the pre-stages of building a new Poor People’s Campaign (before we had the phrase A National Call for Moral Revival) I heard John Wessel-McCoy from the Kairos Center and University of the Poor teach a 2-hour version of this 10-week course. As part of the presentation, he passed around a cotton boll (a piece of cotton from the plant) so we could touch the pod and the seeds and the fibers. I think he wanted us to connect with the cotton so we could perhaps understand something more deeply — the centrality of the crop, the game-changing nature of the cotton gin, the world hunger for the beloved fibers — which all point to the economic underpinnings both of slavery and the movement to end it. As I held that little piece of cotton in my hand, I had a moment of being transported into a time I never lived, a history I barely knew; a period with great significance and mystery and power and torment which had, in my general education, largely been obscured.

I had tried to study the lead-up to the end of slavery once before around 1996 with the Kensington Welfare Rights Union. I was a student organizing with homeless folks, moms on public assistance (soon to be cast off — 1996 was the year Bill Clinton passed TANF welfare reform), and all manner of poor folks in North Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. We had attracted the attention and captured the imagination of many when the union moved itself — about 30 homeless families — into a closed Catholic Church, reclaiming a house of God for God’s people.

[aesop_image img=”https://kairoscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Underground-Railroad.png” panorama=”off” imgwidth=”300px” alt=”Underground Railroad” align=”right” lightbox=”on” caption=”The routes of the Underground Railroad during the Abolition Movement.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

The homeless families drew tremendous support during the church takeover — people came forward from all around offering to help. So we developed the idea of a new Underground Railroad, trying to organize and politicize the good will, the fierce intellect, the resources at hand, and the bravery of people from all walks of life — at the corner of totally illegal & deeply moral — that could somehow support those running for their freedom from poverty. It was an experiment with a lot of lessons and the beginning of my thing for the Underground Railroad. But the study part never really took off in part because our network hadn’t yet done the deep dive into that history. That has changed in the past 20 years.

So as I held that piece of cotton in my hand in Baltimore in 2016, I knew that two hours wasn’t enough and I wanted more. When the University of the Poor offered the class this fall and I was invited to join, I knew to seize it. I threw down and committed to actually doing the assignments and attending every Wednesday night class — even though most weeks I was finishing my reading in a noisy gym at my kid’s basketball practice and I would start the class by phone as I drove us home, throw a frozen pizza in the oven, and finally settle in at my computer on the video call. I craved the class. Not just for the history — but for the light it might shine on my work these days.

How did that go? What did I learn from this course on the movement to end slavery and what can I apply? Well, I am blessed to be part of the Kairos Center staff as a fundraiser (a donor-organizer) for this organization that seeks to build a revolutionary social movement to end poverty. We don’t always call it a revolutionary movement, but to in fact end poverty, we are talking about a fundamental shift in power structures — a broad and deep social and economic change — that’s what I mean by revolutionary.

[aesop_quote type=”block” background=”#31526f” text=”#ffffff” align=”left” size=”1″ quote=”To in fact end poverty, we are talking about a fundamental shift in power structures — a broad and deep social and economic change.” parallax=”off” direction=”left” revealfx=”off”]

We at Kairos are generalists, scholars, practitioners, faith leaders, artists, teachers — and our practice (like the way doctors and nurses practice medicine, we practice movement building) is largely with the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. But we are also about more than that one amazing campaign. We are about an approach to movement building that we think and hope and pray can build and help harness a social movement powerful enough to shift around some big things (some of the biggest things) so that we as a nation, as a globe, use our tremendous resources, technology, and intellect for human dignity, abundance for all, and the best of ourselves — rather than for infected luxury, devastating poverty, and the worst of ourselves.

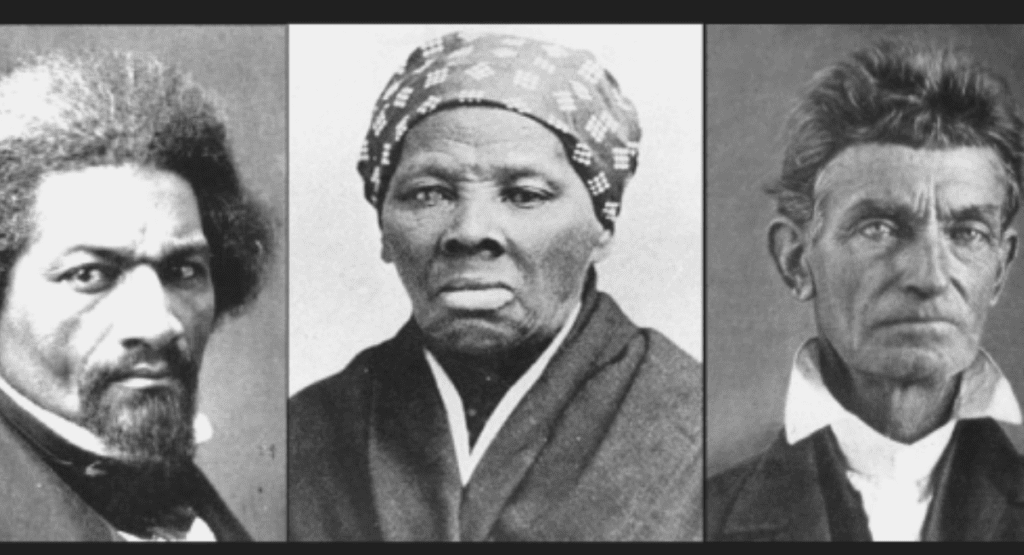

What do I know now of social movement building that I didn’t know 3 months ago? I have more evidence now that there are stages of a movement and some might last centuries, some decades, and some just a few short years. I know that Harriet Tubman was a fundraiser for the Underground Railroad and that the American Anti-Slavery Society offered membership to people who both agreed with their principles and gave funds to their organization — they had to deal with resources just like we have to deal with resources. I know that Frederick Douglass took shit from other leaders in the movement to end slavery because he made a strategic compromise — he believed in immediate and full emancipation of enslaved people, but he went with and pushed forward a program that slavery not be expanded because he saw in that compromise the possibility to gather enough forces to take down the economic and social system of slavery. In the end he was right, but before anyone got to that end, some of his fellow movement-builders gave him shit for it.

I know that conditions and demographics matter. Haiti was different than the American South, and both would have been foolish just to grab the other’s approach and run with it. I know that it is not just any few years when we can accomplish certain things — but a particular few years; a kairos moment indeed. I know that the overlay of stationmasters and certain routes on the Underground Railroad is just that, an overlay gifted by the clarity of hindsight. In the moment it was all about trying what you could think to try, assessing and reassessing the moment, your objectives, your lessons from the past, your relationships, your resources, the moves of your enemy, and the opportunities and obstacles you foresaw and encountered. They had to pick their way through the actual world. And so must we.

[aesop_quote type=”block” background=”#31526f” text=”#ffffff” align=”left” size=”1″ quote=”In the moment it was all about trying what you could think to try, assessing and reassessing the moment … They had to pick their way through the actual world. And so must we.” parallax=”off” direction=”left” revealfx=”off”]

I know that people do not always act just in their self-interest or in pursuit of what is most comfortable or best for themselves and their families. Some folks step up and out to impact a world larger than themselves. I know that different times require different weapons and different forms of struggle. I rarely entertain the role of revolutionary violence, but the role of Nat Turner and others fascinates me. I see that technology like the printing press changed the way that the movement operated. I know that to prioritize running over writing or Douglass’ eloquence over Tubman’s illiteracy is to miss the entire point of a social movement. We must do it all, each according to our gifts and passions.

And this course helped me see that it may be difficult to know whether you are winning or losing. If I can recommend one piece we read that you should read, it’s Frederick Douglass’ gorgeous, light-in-the-darkness speech to his movement beloved after the crushing defeat of the Dred Scott decision. That was a moment when it certainly seemed like they were losing. Like it seems most days that we are losing. But they were just a few years from the beginning of the Civil War, which was just a few years from the win. I remain uncertain — I have more study and learning and assessing to do — but I wonder when we will suspect, as Douglass suspected in that speech, that we are actually closer to winning in all this losing that we’re doing?

Really, that was the primary gift of this study. The winning. The concrete achievement that we cannot tell ourselves never happened — the end of slavery. A small but powerful slaveholding enemy, getting rich off the suffering of millions, was defeated by a unique combination of social forces — and enslaved black people themselves led the way and closed the deal, all without the power to own or vote or many other things we might think necessary. The law of the land changed. Objectively. That social movement won something big and real. It wasn’t everything — a far cry from full justice for all — but a significant, fundamental change in our society and the economy. They did their job, together. And I am grateful for them, our ancestors in struggle, named and un-named in the pages we read. Grateful, humbled, and a little bit in love.

[aesop_quote type=”block” background=”#31526f” text=”#ffffff” align=”left” size=”1″ quote=”I am grateful for them, our ancestors in struggle, named and un-named in the pages we read. Grateful, humbled, and a little bit in love.” parallax=”off” direction=”left” revealfx=”off”]

Today, the Kairos Center and the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival and the University of the Poor and many others are taking on poverty, racism, militarism, and ecological devastation — more evils that are big, ubiquitous, legal and entrenched. Sometimes I think we might be crazy — but if so, we are in good historical company. And while we are not at the end stage of our movement, neither are we at the very beginning. Intentionally and with great faith, we must continue. It is in that spirit and with the humility and energy of an eager new student that I offer for your consideration the movement to end slavery.

Now tell me again. Why would we think we cannot win?

Please consider donating to the Kairos Center today. Harriet Tubman had to fund her journeys and so must we. —Amy