Nathanael said to him, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” Philip said to him, “Come and see.”

John 1:46

Can anything good come out of Nazareth? I want to jump to the end of the sermon and proclaim: Yes! Jesus the Christ! Our savior! The ground of hope! My rock and foundation. The word made flesh and God incarnate.

But, wait, why does Nathanael ask? What does he mean, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” My whole life I’ve known that not only can good come from Nazareth, but the very source of all that is good came from Nazareth.

What is this question?

We know from the gospels of Luke and Matthew that Jesus was born in a dirty stall, laid in a trough. He was born to poor, unwed parents who had been forced to travel, very late in the pregnancy, to a town that was not their own. They either had no family there or their family was too poor to take them in. And now, on top of that, the Gospel of John tells us people would be really surprised if anything good came from Jesus’s hometown. No good can come from Nazareth, is the answer to Nathanael’s rhetorical question.

We can’t always hear it today, because we know the end of the sermon. We know indeed that Jesus our Christ is from Nazareth. And we know that our lives are transformed by this. But we too often read the Gospel through the lens of the conclusion. And when we read too quickly for the conclusion, we miss something important that the Gospel writers want us to understand. Jesus comes from the least of these. Jesus doesn’t come from the centers of religious, political or economic power. Jesus came from the poor, from those who are not expected to bring forward what is good. We know today that the best news comes from Nazareth, but we know that because we read knowing the end.

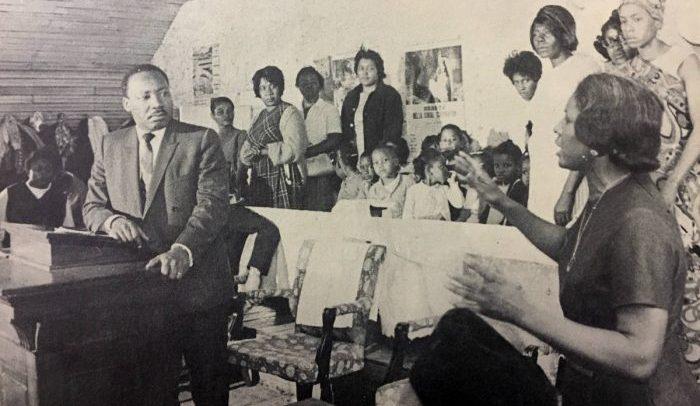

We do the same with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We become accustomed to the national holiday. But the day to celebrate him was not easy or automatic. People fought against it. We forget that the Montgomery Bus Boycott began with the demand that black people in the South can keep their seat only if the back of the bus is full; and that at the time meaningful desegregation was a vision only a few believed could be immanent. We know the conclusion and so take for granted that good came out of Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, and Memphis. Good came from a people who were oppressed, pushed to the margins, terrorized with violence and humiliated with second-class citizenship.

What good can come from places of marginalization and oppression? A people who are willing to fight for the dignity with which God has endowed them. Leaders who see the liberation in the Bible and know God wants it to be real for them. Organizers who go out from places that are seen as nowhere and change not only those places but the whole nation. The end of segregation, the insurance of voting rights, non-discrimination in employment and housing — these were not coming from Washington, D.C. They only became a reality when people from the margins insisted that they be so.

We hear Nathanael’s question about the poor and outcast today. If anything good was to come from the poor, they wouldn’t be poor to begin with. We think that good news comes from those with power, from the center. We think good news comes from those who knew how to bring good news to themselves first. We tend to think that only bad news comes from the poor, the outcast, the dispossessed. But we didn’t get that idea from God.

Fifty years ago, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said good news was coming from the poor. He and other leaders began planning a Poor People’s Campaign where the poor from across the nation and across racial and ethnic lines would come together in Washington, D.C. to proclaim to the nation that our lives were not in order. Our economy is not God’s economy. Racism persisted despite the civil rights legislation. And the war in Vietnam was ravaging poor people at home and abroad.

King had come to see that it was the poor themselves who would be called to be the leadership of this movement, and he began pulling together leaders from poor communities across the country — poor whites, poor blacks, poor Native Americans and poor Mexican Americans and poor Puerto Rican Americans. They were already working to change the conditions of their lives — housing rights, living wage rights, land rights, treaty rights, welfare rights, voting rights and education rights — but they were all doing so in their own silos. They were just beginning to see that if they could come together they could be more than the sum of their parts. They would be good news not only for themselves but for the whole nation and world. In a sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Rev. Dr. King preached,

I must be a neighbor to my neighbor because I can never be what I ought to be until my neighbor is what he ought to be. And you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be … So long as people are poverty stricken, nobody can be totally secure … we are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a single garment of destiny … America will never be totally secure so long as she has forty or fifty million people poverty stricken, even though she has a national gross product of eight hundred billion dollars. No, we are tied together. We are neighbors whether we want to be or not … Jesus is telling us … to be good neighbors. And if we will do that, we will build, right here, a nation which hath foundation, whose builder and maker is God.((Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “Who is My Neighbor?,” Ebenezer Baptist Church (February 18, 1968), p. 13-14.))

We don’t often hear about this Poor People’s Campaign. Rev. Dr. King was killed in the middle of planning it. The poor did come to Washington in the spring of 1968, fifty years ago this spring, but they were reeling from the loss of their leader, demoralized by poor planning and set back by resistance to their attempt to do something totally new.

But perhaps we also don’t hear about the Poor People’s Campaign because it’s too hard to imagine that good would come from the poor when we are told day in and day out that it can’t. But King knew God. And King knew that in God’s time, in God’s kingdom, good news comes from the margins. Describing who would come together for the Poor People’s Campaign, King said,

By the thousands we will move. Many will wonder where we are coming from. Our only answer will be that we are coming up out of great trials and tribulation. Some of us will come from Mississippi, some of us will come from Cleveland. But we will all be coming from the same conditions. We will be seeking a city whose Builder and Maker is God and if we will do this we will be able to turn this nation upside down and right side up. We may just be able to speed up the day when man everywhere will respect the dignity and worth of human personality and all will cry out that we are children of God.((“The State of the Movement,” SCLC staff retreat, Frogmore (November, 1967).))

King is describing that through God good news still comes from where we least expect it. Because God does not think that some people are more worthy than others. And God calls us to refuse that idea, too. God calls us to a reordered society that respects the dignity of all creation.

Fifty years later we are hearing the call to have the faith that allows us to cry out that we are the children of God. Across the nation people are taking up a Poor People’s Campaign again. This good news is coming from fast food workers, people whose water has been poisoned by lead, people who have lost their healthcare or can’t afford to use their health insurance, and people of good conscience everywhere who know that, in the words of Dr. King,

I must be a neighbor to my neighbor because I can never be what I ought to be until my neighbor is what he ought to be … We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a single garment of destiny.

We are approaching the fiftieth anniversary of King’s assassination and his words are no less true today. The good news of the people of God is never easy news. We cannot skip to the conclusion, because we are the ones being called to take up the work. We are called to answer this invitation to discipleship, to hear God’s call to be tied together, where all persons are valued and there is no longer room for poverty, racism and war. Our God comes to us in unexpected ways. There is indeed good news from Nazareth.

This sermon was originally preached by Dr. Colleen Wessel-McCoy at the Church of the Holy Apostles, Brooklyn on Sunday, January 14, 2018.

Buy Dr. Wessel-McCoy’s book, Freedom Church of the Poor: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign. Fortress Academic, 2021.