Willie Baptist has spent over 50 years educating and organizing among the poor and dispossessed beginning with his formative experience in the Watts uprisings in 1965. He is currently the co-coordinator of poverty scholarship and leadership development at the Kairos Center. Six years ago, in light of the killing of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri and the violence that followed, Willie reflected on his experience in Watts. Willie noted how in both cases the outbreak of violence was precipitated by a combination of long-standing abusive and racist police tactics and severely depressed economic conditions, including high levels of youth unemployment. The global pandemic of COVID-19 has only intensified the underlying health and economic crisis, and it is threatening to provoke similar violence today as people are pushed into more and more desperate positions.

Elected political leaders and the wealthy few that influence them understand the threat posed by the currently worsening situation and have quickly responded by infusing trillions of dollars into the economy. Some of this money has gone directly to people that need it, but most of it has been used to prop up businesses in the hopes that consumption and production can “return to normal.” For the 140 million poor and low income people in the US before the crisis there is no desire to return to “normal.” If the efforts of those in power fail and people are pushed further and further into poverty there is overwhelming historical evidence that there will be a backlash. History also tells us that the State tends to respond to these outbreaks with the use of State controlled violence — police and military, and through the time worn tactics of divide and conquer.

Baptist’s reflection on Watts and Ferguson is full of relevant lessons for the situation we confront today. It has insights on how our social movements have been outmaneuvered, but also shows where they found and exploited weaknesses that led to victories. In the broadest terms it makes a powerful argument for how important it is for us to study history and develop leaders who will be prepared to resist the divisive tactics of the powerful and steer the energy of our struggles and the chaos of unsettling conditions into the organization and unification of the poor and dispossessed.

The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, like the Campaign the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. helped to launch in 1968, is a model for how we can build the unity and power of poor and dispossessed people. The Campaign follows the leadership of the poor in seeking to fundamentally transform the structural evils of our society and realize a social vision led by and centered around the needs and sacred value of all people. The lessons in this article are critical for leaders in this Campaign and other efforts to organize the poor. We hope these lessons will be studied and shared, and combined with the insights and experiences of others in the days ahead.

John Wessel-McCoy interview of Willie Baptist (Sept. 10, 2014).

John Wessel-McCoy (JWM): Willie, could you give us a bit of the context in terms of your involvement in the 1965 Uprising in Watts, California and how that experience informs your reflections on the 2014 Uprising in Ferguson, Missouri?

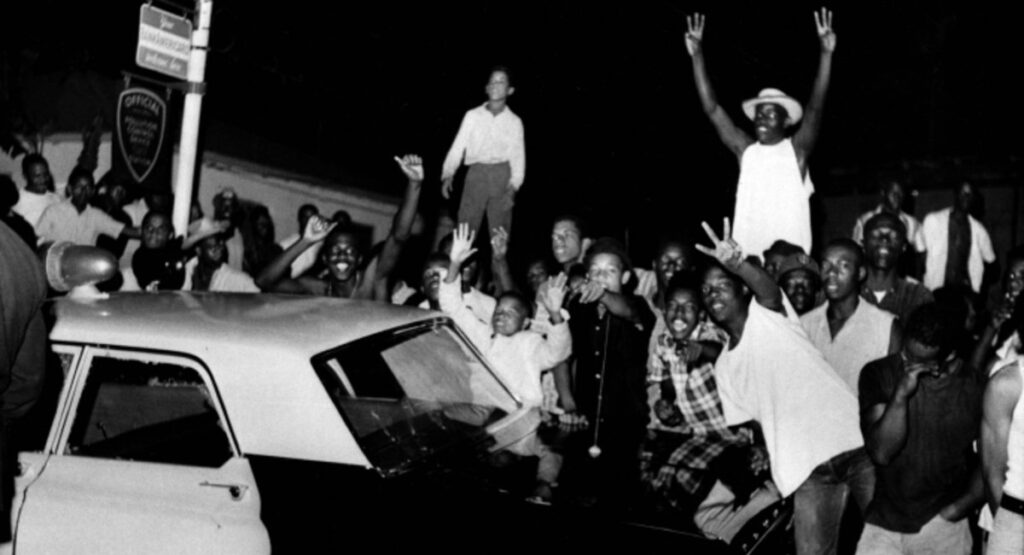

Willie Baptist (WB): Well, I’m 66 now and I was seventeen years old, just a year younger than Michael Brown, when particularly oppressive police relationships in the black ghettos, triggered mass uprisings. Police aggressive acts and killing precipitated smaller outbreaks of protests in black ghettoes such as in Harlem, New York, which predated the larger uprisings of the last half of the 1960s. However, it was the much larger 1965 ghetto uprising in Watts, California that inaugurated the largest violent social upheaval since the United States Civil War.

Watts was mostly a segregated poor black neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles. It was one of, if not, the poorest community in the entire state of California. It erupted in the small Watts community. However, the police and the National Guard had cordoned off an area much larger than Watts. Watts, as a community, had anywhere between forty- to fifty thousand people, but the area they cordoned off had from 400- to 500,000 people. Which was a broader black community, if you will. It was an area in which the events, which was sparked in Watts, began to spread throughout South Central Los Angeles.

We were then also confronted with a militarized police force backed by the National Guard. Military helicopters and other such equipment that had been used in Vietnam were deployed. The accumulation over the years of abusive police practices reached a boiling point at which pent-up rage and mass resistance were unleashed. Incidents of the escalated movement of police and military forces, the massive arrests and killings left an indelible stain on my brain. Today I’m still a student of what happened during those times of ghetto revolts in Watts and throughout the country.

Since then, I’ve been able to come to conclusions about things I couldn’t have to come to while in the midst of those events. Even so I still find myself personally reliving these events every time you hear about police abuses, particularly as it concerns black youth who are the dead victims of those abuses. So the rage I’ve been building up since the age of seventeen is still there and often re-triggered and I find it hard not to respond emotionally and tending to revisit those times over and over again. The great and global 2008 crisis contributed largely to the election of Obama as the first black President. The crisis has also given rise to mass economic and social dislocations and an acceleration of police abuses and violence. This has precipitated in resistance and protests significant so called “riots” in black communities. There have been about five such outbreaks under the administration of the first black President and under the continuing conditions of dislocation and devastation left by the economic crisis. I’m reminded of the impoverished economic conditions like those in Watts during the time of the uprising where we had upwards of 60-70% unemployment among the youths.

Unemployment and bad economic conditions basically described the black ghettoes throughout the country. Anyway it is clear, upon deeper reflection, that what made the ghetto the ghetto was this economic situation, not just police racial oppression. This is despite the official findings of riot commissions set up by the President. The mostly police sparked “riots” were defined by Presidential commissions as “racial.” Such commissions as the Kerner Commission (officially called the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders appointed July 28, 1967 by Lyndon B. Johnson) characterized the ghetto uprisings as “race riot,” as essentially caused by the divide, the continuing divide, between “white America” and “black America.” This “finding” appealed to and reinforced a historically evolved extremely limited and emotionally charged racialized view in American thinking.

So the recent police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson combined with the sensationalized and superficial coverage of mainstream media cannot but restrict perspective and rivet anger preventing you from seeing the context and interconnections of issues. It prevents you from seeing beyond the leaves and branches of the problem to it root cause. The sight of a dead body of a youth laying on the street for four hours before the police allow it to be finally and properly taken away. You could see how this can arouse and rivet the anger of a community.

This and similar other killings have again triggered feelings of rage that still exist deep inside of me dating back as far back to the traumatic experiences of Watts. So reflecting on what I come to know about the Watts situation and the Ferguson situation and all the other recent “race riots” as described by mainstream media I begin to see the interconnection of factors that has been involved in these complex processes. I also see how mainstream media has limited most people’s view of these outbreaks. They have the people only focusing on and discussing the tree and not the forest of factors involved in these processes, especially the complex of connected issues and problems coming out of the present economic situation. The conditions that gave rise to the Watts Uprisings are today beginning to develop and worsen in other distressed communities including working class white communities. And bad economic relations gives rise to bad police relations and we can expect the increasing and spread of similar explosive events.

I mean we’ve got to put the events such as the Ferguson outbreaks into context. This is connected to the stepped up police activities in relationship to the Occupy eruptions which included many students who are accumulating debt facing a situation where they have very low economic prospects. So they take initiative to protest these worsening conditions and then that reverberates across the country in terms of other Occupies and then we witnessed the police reaction to that. But also globally and the police role in the Greece situation, the police role in Spain, the intensification of police activities that are connected to the forced illegal activities in poor white and brown communities here in the United States, and throughout Latin America. I mean, the police brutality in the favelas have intensified in Brazil. Here every year, something like 400 youth, or black youth, have been killed during police activities, but Brazil you have thousands, I mean thousands and thousands, dying. And there’s this relationship between economic conditions with the problems of race relations and the problems of police relations. The discussion about it and the activities in response are limited in such a way that the full scope of it and its causes are not understood and dealt with.

I think that the only way we are going to get off this historical merry-go-round repeating history, is to learn from history and the fact that every one of the uprisings that have taken place recently, as well as the ones that have taken place historically, have always been characterized by the of leading and militant activity of poor youth. Vast sections of the youth, many are unemployed and educated with little or no prospect of being absorbed into the economies of the Mideast and northern African countries like Egypt and Tunisia. With no jobs and an imperiled future they are being compelled into a fight for their lives and livelihoods. They are finding themselves in the forefront of these uprisings and being beaten back by police and military activities.

Ferguson and the killing of a black youth are not an isolated racist event. It is part of a bigger picture, the causes and effects of which suggest the kind of solution that is much broader, and much more encompassing, than what is happening right now. And what has happens right now is more or less a repeat of history.

Ferguson and the killing of a black youth are not an isolated racist event. It is part of a bigger picture, the causes and effects of which suggest the kind of solution that is much broader, and much more encompassing, than what is happening right now.

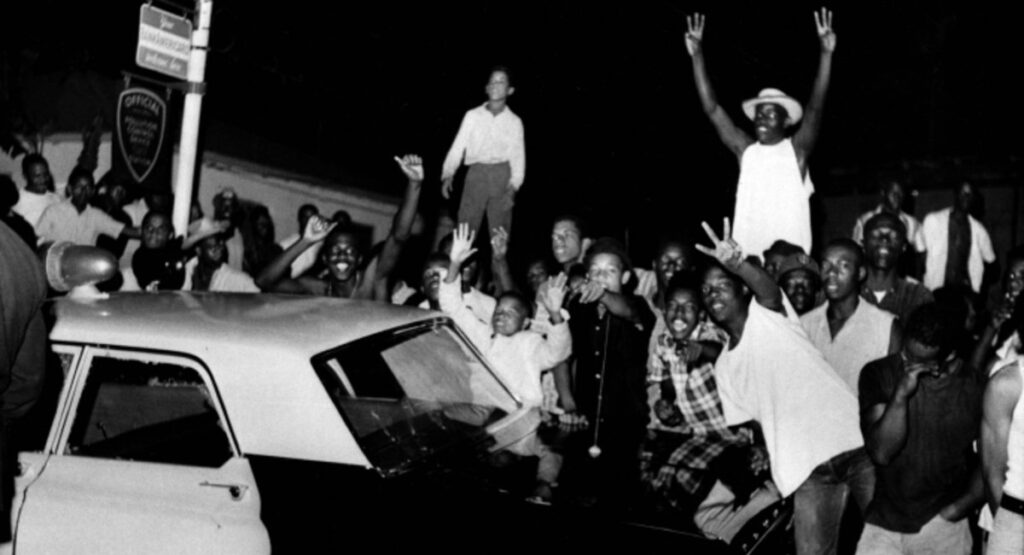

When you take a deeper look at what happened during the ‘60s black ghetto uprisings you see three major responses that were of major significance and hold some very important lessons for understanding the social problems we are dealing with today. First, the largest response was an all-white, all-classes, law and order backlash to the police-sparked mass black ghetto protests. The second response, which was related to the all-white response, was the all-black, all-classes Black Power movement, which eventually resulted in the advocacy of black capitalism, black businesses, more black cops and the election of impotent black politicians. And both of these two responses fed off each another and combined to maintain and deepen the historic disunity and mutual fear between poor whites and poor blacks. The flipside of this disunity has always meant the pre-emption of the unity of the very social forces necessary for attacking the exploitive and oppressive economic conditions that have largely created the ghettos and resulting bad police/community relations in the first place.

In addition to the higher rate of unemployment and poverty wage jobs, the impoverished conditions of the black ghettos also found expression in the mass resistance of the uprisings. One of the main forms of mass participation, young and old, was mass looting, that is the all-out violations of legal property relations. People protested by taking what they needed economically. That is, they took things like, food, clothing, baby diapers, and so on and so forth. While poverty among blacks and other nonwhites has always been disproportionately greater and more concentrated in segregated ghettos, barrios, and other deprived areas, poor whites have in absolute terms outnumbered poor blacks and other poor nonwhites. The discrepancy and disproportion is due in large part to historically evolved United States forms of racism and particularly through the racially segregating housing codes and covenants. The racist attitudes and fears continue to dominate our thinking. And the Presidential Commissions that were set up to study what they essentially labeled “race riots” reinforced and encouraged this thinking and the two racialized major movements this thinking contributed to.

This thinking is no easy thing to shake and change as it is historically rooted in a culture and systems of education and entertainment dominated and paid for by a profit-making and poverty-producing economic system. This economic system and dominant thinking are upheld by an exploiting and ruling class who has vested interests in the maintenance of that system and thinking. It is a thinking that has the mass of the people seeing only the surface and separateness of things. It is a thinking that is fixated on a tree and not the forest fire or at most it only sees the separate trees not their connections to each other and to the ecosystem of the forest as a whole. It is a thinking that has no patience and discipline for a deeper analysis of events that reveal their complexities and interconnections. The prevailing focus on racial oppression as an isolated factor is derived from this long established mindset and in turn reinforces a narrow and categorical thought process and approach. And this approach like a broken record keeps us repeating history, keeps us on a seemingly interminable merry-go-round of police killings of black youths and then black protests with a few left/liberal whites in futile support.

During the Watts Uprising I also saw a militarized police force. Like what has been given much attention in corporate media, this militarization of police also took place and was stepped up in response to unfolding of the 1960s’ ghetto uprisings throughout the country. Like similar governmental programs today, LEAA (Law Enforcement Assistance Administration) programs were set up to further promote, among other things, this militarization with police departments purchasing military gear and weaponry. The all-white Law-and-Order backlash Movement really served to strengthen these police policies by basically becoming a social base of support. The related Black Power movement was reduced to being utilized as an added excuse and supplement for this support despite its legitimate but limited and ineffectual protests of police wrong doings.

With the lack of political consciousness I had at that time, I got caught up in the Black Power movement. So I too got caught up into this cruel manipulation of the Powers That Be.

JWM: It’s no mistake though that the state of California produced Reagan out of Watts. It was Reagan’s launching pad.

WB: Yes, the reactionary Ronald Reagan’s gubernatorial election campaign successfully used the mass Law-and-Order backlash sentiments. His campaigned loud and long against what he called the black criminals of Watts and he was elected Governor on that basis of it. The all-classes, all white Law-and-Order movement also added to Richard Nixon’s successful Presidential campaign declaring that this movement constituted the new “Moral Majority.”

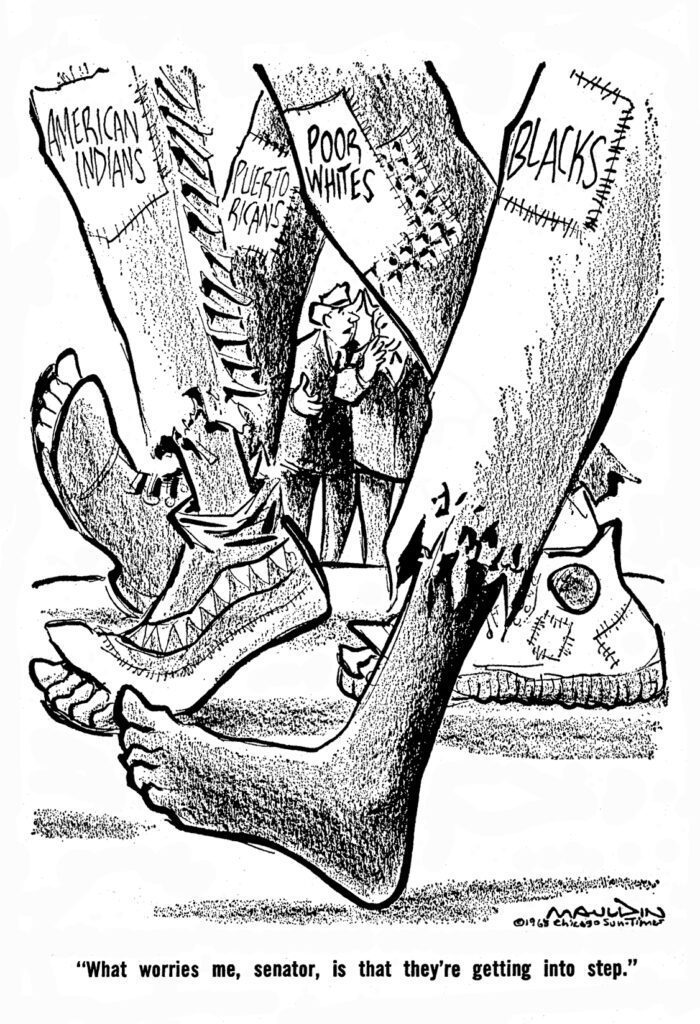

But there was importantly an attempt at a third response to police brutality and the ghetto uprisings. It was the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s launching and organizing of the nonviolent Poor People Campaign, which aimed at uniting the poor and dispossessed across color lines on the basis of their common economic needs. Most strategically, this included poor whites. This third response was tremendously crippled by the political assassination Dr. King. All the evidence of the prosecution effectively proved in the 1999 Memphis, Tennessee District Trial that Dr. King was too a victim of police and military conspired violence. They proved that a poor white man was falsely scapegoated as a diversionary device. The American public, both black and white, were susceptible to believing in this false accusation, which had been manufactured by the intelligence agencies, particularly the FBI.

The trial also proved that Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign, his last initiative, posed both a political threat and an immediate military threat involving the demoralization of the frontline US troops in Vietnam, which consisted mostly of poor whites and poor people of color. The threat on these two levels was not about Dr. King the man but about the message he in particular communicated through the launching and organization of the campaign.

I think the obscuring of the last years of King’s life, is obscuring the fact that neither the “right/conservatives” nor the “left/progressives” are in power. It’s the dominance of big capital that manipulates from a more or less center position both left and right, both the liberal/progressive and the conservative, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. This manipulation is the application of the political formula of divide and conquer specifically evolved out of US history. Dr. W. E. B. Dubois in his magnum opus, Black Reconstruction explained the origins of this doctrine. He described what could be called the old “Plantation Politics” of how the poor whites were used to control the black slaves and how the super profits attained thru the super-exploitation of the black slaves was used to entice the poor whites. Throughout history and in my lifetime this formula of power and control has been replayed over and over again. And even in my militancy in joining the Black Power movement and resisting these attacks on black youths, I unknowingly played the part of manipulated pawn in a much larger power game. At that time I didn’t have the political consciousness to get out of the box of this kind of formula of power. Again we are witnessing in the responses to the outbreak in Ferguson the same merry-go-round of repeating of a history that is not understood.

However Dr. King developed enough of a consciousness that allowed him to begin to get out of the box of being just another one of the manipulative pawn pieces. His third response was an alternative to the police riots and the two major responses alluded to earlier. His response was a direct challenge to the replay of the old “Plantation Politics” of racial division and manipulation of the bottom classes Du Bois described, the old pattern of power and control that has evolved out of US history. His response was a strategic departure from a Civil Rights Movement that was largely limited to ending only de jure segregation and discrimination–or legal apartheid in the United States. His response was to begin to pull together the economically exploited and impoverished sections of all ethnic groups despite the de facto segregation of these communities — the ghettos, the barrios, the slums, etc. He was assassinated before he could complete this mission of his message.

Power for poor people will mean having the ability…to make the power structure say ‘yes’, when they may be desirous of saying ‘no’.

Rev. dr. martin luther king

Military intelligence had done surveys during the course of the uprisings and they found that despite his well-known commitment to the nonviolent philosophy, Dr. King was polled as the most respected of all the leaders by the most militant and youthful rioters. Malcolm X came second. Dr. King had gained this respect because of his bravery in risking death and going to jail, because of the religious values deeply embedded in most everybody even if they don’t go to church. By the times of the uprisings he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and acknowledged as the main leader of a fairly wide network of civil rights organizations. By taking up opposition to the Vietnam War, he at once moved to the forefront of the largest struggle for peace in US history. All told he had become a leader of the three major currents of resistance along with his having attained international legitimacy and influence. In his launching of the Poor People’s Campaign he threaten to unite these major currents against the economic interests and foreign and domestic policies of the Powers That Be.

In my study of Dr. King’s last years I see how he came to understand the interconnections of the major problem he called the triple evils: the evil of economic poverty, the evil of militarism, and the evil of race relationships, and how they are all inseparable and you can’t resolve one without resolving the others. What he came to realize is that those issues and more are embodied in the position of the poor. And if you can unite the poor you are uniting and dealing with all of those issues at the same time. The way the issues of poverty and police brutality has been framed in separate categorical silos. Poverty is looked at as something over here, the housing crisis and all the other symptoms of poverty—the healthcare crisis, food and water crises, the crisis in education, and the deadly consequences of the environment on the poor are all seen as disconnected issues. This superficial and false view serves to preempt the kind of motion that Dr. King trying to enlighten and organize.

Since the 2008 the continuing stagnation and devastation of global economic crisis is spreading to white neighborhood similar conditions of economic depression and political repression that caused that mass eruptions in Watts and other ghettos during the late ‘60s. We are now beginning to witness more political instability globally and more eruptions of protests breaking out globally.

The new situation is requiring more than ever that we reignite the strategic approach Dr. King inaugurated in the last years of his life. I think that one of main the lessons we must take from the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign is that we do not need just one Martin Luther King but that we need instead many Martin Luther Kings. In other words, we the replication of many leaders who are clear and committed to his strategic approach of uniting the poor and dispossessed as a leading rallying point for the marshaling a broad and powerful movement to abolish all want, all injustices and human indignities.

JWM: We are working toward reigniting Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign for today and we’re doing the work over the next few years of righteously building this Poor People’s Campaign. And the fundamental strategy for Dr. King and the Poor People’s Campaign then and for today is uniting the poor and dispossessed across color lines on the basis of what they have in common. Ferguson really exemplifies the disunity of the poor and dispossessed. It’s a reflection of the relationship between race and class in this country. How do we approach Ferguson and the many other Ferguson’s that we anticipate are going to break out as conditions worsen?

WB: Clearly what’s missing are leaders with the historical perspective, strategic approach and sincere and serious commitment of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I see first of all this need. Such leaders are not like Athena who was born out the head of Zeus fully equipped with wisdom and weaponry. They are systematically educated, trained, and inspired. We need Martin Luther King-like leaders who can see the more complicated, deeper and bigger picture of social reality in terms of the interconnections of the problems of injustices and the necessary inseparability of their solutions. Corporate mainstream and elite media would have us not see the truth of this reality. That is why they are focusing public attention on the police killing of Michael Brown and the response of protests is such a way as present the problem as isolated one and simply about race. Further national and global debate has been focused on the images of a militarized police force and the issue of political brutality in a way the limit discussion to only violations of civil rights and covering up the deepening problems in communities like Ferguson of violations of economic human rights.

Since the 2008 crisis and while the first black President has been in office there have been at least five major killings of unarmed black and brown youths. The worsening economic situation is resulting in especially an increasing death toll of the impoverished including from among growing ranks of poor whites. If you are a youth with no decent job prospects and therefore join the armed forces to die needlessly in war along with the massive numbers of war deaths of unemployed and poor Iraqis and Afghanis you are just as dead as being shot dead by the police. The same is true with unnecessary and increasing drug-related killings and deaths from the epidemic of diabetes. According to the World Food Organization, more people die from hunger than in from the wars that are currently being wage around the world.

The worsening economic situation is resulting in especially an increasing death toll of the impoverished including from among growing ranks of poor whites. If you are a youth with no decent job prospects and therefore join the armed forces to die needlessly in war…you are just as dead as being shot dead by the police.

So I think that it’s incumbent upon us to take up the mantle of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., not so much the man but the message of his ministry, which would mean going beyond the leaves and branches of social problem and getting at the root cause. It would mean stepping from behind the pulpit and hitting the pavement and working toward the true and just solution.

Because otherwise, the problems as has been manifested in Ferguson are going to be framed in the way that they can’t be solved, they can only be repeated again and again. Like Dr. King once stated, we are not going to have the accurate prescription to the disease if our diagnosis of the disease is inaccurate. In other words, if your diagnoses of Ferguson is that it is just a race issue, when in fact it involves and is connected to all these other questions, then you’re not going to have the right kind of solution or be able to build the right kind of solution to the problem, we’re just going to have to relive the inhumane horrors of history.

JWM: Looking at the media coverage of this event, there’s pundits that come on, and I don’t know how many times I’ve heard someone in the news say, “Well Ferguson is an example of how we as a nation need to have a real deep and honest conversation about race.” And they say it over and over again. I really want to know exactly what people imagine that conversation would be like and who’s having it. The events that happened in the wake of Michael Brown’s murder, and his being gunned down, strikes me in a very personal way as far as having grown up not very far, at all, from St. Louis. I grew up in Decatur in down state Illinois, and I’m seeing what’s been happening to my town. There’s real economic devastation that’s been happening there and that’s been impacting across color lines, always disproportionately impacting the black community there but more and more becoming something that is generally impacting across color lines.

I know Illinois better than Missouri, but it’s true in both states that if you go outside the cities, the St. Louis metro area — out in the rural areas and small towns, you get to part of the states where the prisons get built. At the same time, you see how tough things are getting there and this whole thing really strikes me… that a big thing that is not being said is how much this sort of control, this violent control, through the means of police and the criminal justice system having control of these communities of color are just as much really about how you control poor whites and the white masses insofar as disunity goes. The justification for this system of repression can, and will be, turned against anybody, ultimately, as things get worse. We get this concept of “Plantation Politics” from studying W. E. B. Du Bois on this question of how the poor blacks are used to control the poor whites and the poor whites are used to control the poor of color. It’s a real clear example to me, but also I see potential. I don’t think it’s a done deal, I don’t think that this unity is impossible. It’s not going to happen on the basis of how the conversation is generally framed about what happened in Ferguson.

I find it very telling that among many progressives, including many of my friends, are really trying to wrestle with this. I find it really curious that even when people try to suggest this question around class and the class nature of this, there’s almost a knee jerk reaction to say, “Hold on, you’re not talking about race.” And I think that’s very interesting. That view, or that response, really indicates something about how dominant views or understandings, when these sort of things happen, are propagated and sustained. It’s almost like when I hear people say this; I’m like would it kill you to spend five minutes to consider this aspect. Not in isolation from race and the racism question, but to even consider this…and so, I think the challenge of leadership is to figure out how to be able to tie it all together…it’s so evidently necessary.

WB: This is where an understanding of history provides some guiding lessons for considering where we should go on the issues of race today. The economic collision of the industrial north with the slave economy brought about the response of Slave Power that culminated in the historic Dred Scott Decision, which concluded that blacks had no rights that whites are “bound to respect.” It was clear that that racist and white supremacist decision was connected to the class economics of American slavery. It was a product of the fact that the necessities of the growth of the slave empire was cutting in on the economic livelihood of the West. This inescapable fact gave strength to the agitation and educational campaigns of the abolitionists, which showed clearly the connection of this stepped racial attack on blacks to the economic self-interest of the masses northern white workers and western poor white homesteaders.

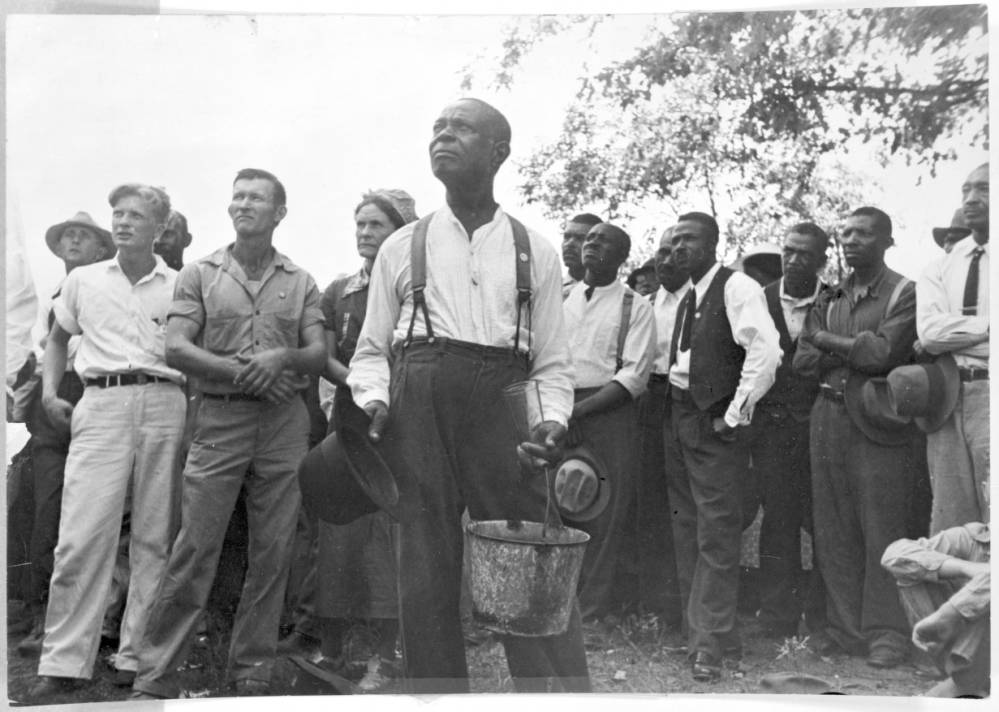

There are other parallels in history that we can learn from and utilized as guiding lessons in analysis of and actions in response to problems of economic and racial injustices we are being increasingly confronted with today. Another such parallel is the 1930s struggles and organizing of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Due largely to the economic devastations of the Great Depression no matter the color the Southern Tenant Farmers Union brought together out of necessity poor whites who were influenced by the Klan and poor blacks who were influenced by the Marcus Garvey movement. They came together based on what they have in common, and the agitation around that allowed for a discussion of race that get more to the deep economic root and political complexity of it. W. E. B. Du Bois’s discussion in his 1935 Black Reconstruction, is a deeper discussion of the questions of race and class and the struggles around them found expression during that pivotal period of US history. The involved analysis he displayed in that magnum opus revealed how he had developed a far deeper grasp of race than his earlier understanding of racial oppression. For instance is his 1904 famous and more talked about book, The Souls of Black Folk, discussed race relations separate from the economics and class relations. In contrast Black Reconstruction is not just a discussion of how Wall Street and big industrial capital after abolishing slave capital and through defeating reconstruction came to dominate the country economically and politically. It is also discussed the central role race played in that violent drama describing how both Slave Power and eventually wall street utilized a time-worn “Plantation Politics” formula to manipulate and ultimately defeat a disunited class of the dispossessed (or propertyless) black and white workers.

You can’t understand class and its consequence, poverty in this country, unless you understand race and you can’t understand race and its consequence, police brutality, unless you understand class. All of the one sided racial propaganda that have bought and paid for by the rich ruling class down through US history has led to the current limited appreciation and approach we are witnessing today in the responses to injustices like that in Ferguson. If we are going to change the prevailing misconception of race and class that most people have and if we are going to change the wrong and dehumanizing direction this country is heading, we’ve got to organize to change it — there’s got to be an organized effort to do it. The solution and change in these injustices are not going to come spontaneously. And that effort has to include this understanding of the relationship of conditions with consciousness. In the condition where people are being evicted and laid off no matter the skin color the discussion of race must be a much deeper than simply white people don’t like black people. And yet, that’s the predominant way people understand the problems that beset this country. And so when incidents like this happen, people are always going to respond in a way that doesn’t resolve but in fact prolong the problems. What make matters worse is that incidents like in Ferguson are to continue to happen and multiply as the economic and social conditions that rise to them worsen. History teaches that bad economic relations give rise to bad police relations as well as other forms of social and political oppression.

You can’t understand class and its consequence, poverty in this country, unless you understand race and you can’t understand race and its consequence, police brutality, unless you understand class.

That is why we must finish the unfinished business of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s by reigniting the Poor People’s Campaign along the lines of the key principle he preached and practiced. That principle being the struggle to unite the poor and dispossessed across color lines as a “new and unsettling force,” the only social force capable of awakening the necessary critical mass of the American people to abolish unnecessary human misery and human indignities. The launching and organizing of a new Poor People’s Campaign is needed more now than ever. Such a campaign would highlight and unite the struggles around needs we have in common. This would constitute a social force whose interests it is to abolish racial and all other inequalities and prejudices in the context of these struggles. This campaign would serve to provide a space and opportunity to have the newly emerging leaders, the particularly young leaders, to unite in strategic dialogue and coordination of efforts.

Under today’s conditions this campaign is going to have a pronounced global dimension. For example, right now our brothers and sisters in South Africa, the shack dwellers, have been also dealing with unjust assaults and deaths as a result of escalating police abuses. I recently read an article that compares the amount of police killings in the favelas in Brazil to the amount of police brutality in the black ghettos in the United States and it shows that these incidents are happening more so as the result of worsening conditions. It suggest that conditions of the favelas and resulting growth police assaults are coming to the ghettoes, suburbs, slums, and barrios in the United States.

JWM: History teaches clearly in both positive and negative lessons that the only way of dealing with dangers and opportunities presented by such socially explosive and difficult times as these is through the unity and organization of the poor and dispossessed across color lines and all other lines of division. Willie can you give us some final words on this urgent necessity?

WB: Dr. King in his last years spoke of this necessity. He spoke of the only answer to the pain and suffering of poverty is the united actions of the poor. As a minister of faith he felt deeply about this and gave his life teaching and fighting for this unity. He spoke of it being a question of organization, which would serve a “the freedom church of the poor” moving the hearts and minds of the broad masses of the people toward the economic and political emancipation of all of humanity. And such a church would be different from the prevailing churches, being totally different from both black and white churches that uphold a theology that accept the disunity of the poor and justifies this cruelly unjust society.

The launching and conduct of a Poor People’s Campaign must be taken into account this new and unprecedented and explosive situation. Dr. King’s vision of “a freedom church of the poor” is the answer. This church will have no walls and everyone will be welcome into this fight for human dignity and abolition of all poverty forever. This theology and this church will challenge all churches, white and nonwhite. They will challenge all theologies that fail to come to terms with the immoral and unnecessary problems of poverty in the midst of plenty.

I see this period of the unprecedented and tremendously productive technological revolution and great global economic shifts as a moment of great danger and great opportunity. This is indeed another kairos((Kairos meaning a time when conditions are right for the accomplishment of a crucial action: the opportune and decisive moment. —Merriam-Webster)) moment to build a new movement of global proportions to move the world to a better place with dignity and justice for all of God’s children. Every major turn in history attended by great economic shifts has necessitated and made possible changes in economics, politics, and ideology. This kairos moment is giving rise to a great opportunity to develop a new theology and a new consciousness and new theories and a new and powerful social movement for social transformation. As economic conditions continue to deteriorate, we can expect more Fergusons, more Watts erupting especially in poor and dispossessed communities and worldwide. One day when asked by a youth “What do we do?” Frederick Douglas answered, “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!” Well today we need to be agitating, agitating, agitating so as to educate and activate toward a deeper and broader understanding of the race question, the economic question, the global question and how all the injustices connected to those questions are inseparable and cannot be resolved separately. We can also expect that people are going to question things much deeper and if we can answer those questions, we can organize a network of leaders and teachers who can then agitate, educate, and organize a broad social movement to abolish the poverty-producing system, which is the root cause of all social and economic injustices.