Poverty, the Bible, and Jesus’ Poor People’s Movement

In recent weeks and months, particularly following President Obama’s presentation to the “Poverty Summit” at Georgetown University and the media coverage of that summit, the debate and discussion on the poor and poverty and the role of the government, religious institutions and individuals in addressing poverty has intensified. Pope Francis has played an important role in lifting up the importance of Christians tackling poverty, recently stating: “Poverty is precisely at the heart of the Gospel. If we were to remove poverty from the Gospel, people would understand nothing about Jesus’ message.” ((Glatz, Carol, “Pope Francis: Concern for poor is sign of Gospel, not red flag of communism” Catholic News Service | Jun. 16, 2015))

This article enters into that discussion by directly challenging statements currently being made by Evangelical Republicans, and others across the political spectrum, on the inevitability of poverty and the pathology and moral inferiority of the poor. It also challenges many “progressive” Christians who, in my estimation, draw on the Bible to argue for economic rights and dignity for poor people, but avoid some of the most popular and most challenging passages; resorting to selectively quoting the Bible instead of holding it up as a whole text that demands justice for all of God’s children. They often leave out the agency of the poor in the Bible and today, thereby suggesting that charity is the only solution to poverty. This creates a disconnect between efforts of well-meaning religious leaders and the popular theology that is both hegemonic and dominant among the majority of Christians. We need a popular theology of economic justice that embraces the whole Bible, one that shows Jesus’ ministry as a revolutionary movement against the evils of Empire and poverty.

Jesus’ Teachings on Poverty and the Kingdom of God

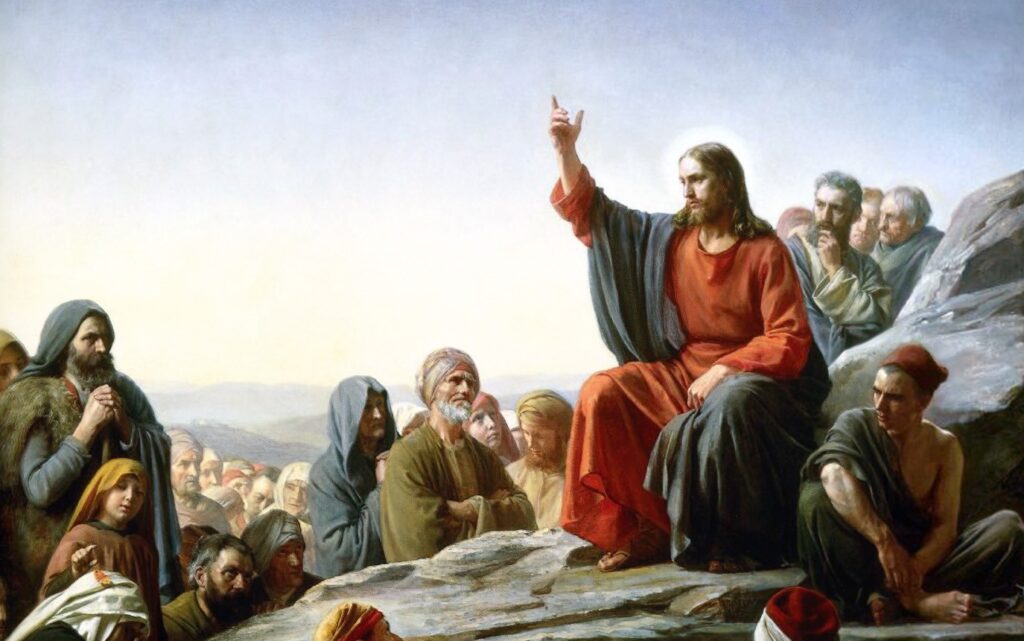

Jesus’ teachings and actions around poverty, wealth, and power, especially in Matthew’s Gospel, lend support to a portrait of Jesus as a social movement leader with a revolutionary economic program. Jesus’ social and economic teachings as laid out in the Sermon on the Mount and his other lessons show him to be a “New Moses”: a liberator to the Galilean villages and Syrian towns who brings new instruction and a new understanding of law and justice to a people in need of dignity and freedom.((Combrink, “The Structure of the Gospel of Matthew as Narrative,” 62.)) Jesus’ disciples are learners of and leaders in his lessons.

Among these lessons, special attention must be paid to the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5-7), where there is a truly revolutionary set of teachings about poverty, debt, and other economic issues. The Sermon on the Mount includes the Beatitudes (Matt 5:1-12), the Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:9-15), the choice between honoring God and Mammon (Matt 6:24), and God’s provision for the material needs of the people (Matt 6:25-34). The first main teaching in the Sermon on the Mount is the Beatitudes. Similar to how the phrase “the poor are with you always” has been used to justify poverty, the presence of “blessed are the poor in spirit” in the first Beatitude in Matthew (as opposed to Luke’s Sermon on the Plain, where he speaks simply of the “poor”) has often been used to spiritualize the gospel and claim that Jesus is not concerned with material/economic issues.

As Biblical scholar William Carter explains, this reference to poverty of “spirit” is not a spiritualization of poverty, but a further description of poverty and despair. The Greek word pneuma is often translated as “spirit,” but also means “breath.” These people, whom Jesus is referencing, are metaphorically poor in breath, on the verge of death; they are being denied life.((Carter, Matthew and the Margins, 19.)) Other scholars like Leland White agree that the concept of “poor in spirit” refers to those who are down and out, the most marginalized. He insists that because the word “spirit” connotes breath and life, being poor in spirit actually intensifies and emphasizes the material poverty of Matthew’s community. White argues that the general term “poor” could have spoken to more than economic deprivation, but never excluded it. In other words, “blessed are the poor” cannot mean “blessed is poverty”. Rather it indicates that the Kingdom of God would end their material deprivation and that poverty existed (and still exists) as a result of the society as a whole not being responsive to the will of God.((White, “Grid and Group in Matthew’s Community,” 61-88.))

Later in Matthew’s Beatitudes (in Matt 5:6), Jesus blesses those who hunger and thirst for justice. This addition of justice/righteousness to the condition of hunger is similar to the inclusion of “in spirit” in the condition of poverty in Matt 5:1:

“The traditional translation (“righteousness”) has led to a pious individualist interpretation. The point rather is that with the coming of the kingdom of God to the poor, justice will be realized or effected for them, with sufficient food, clothing, shelter, and so on, for a basic livelihood. Jesus reaffirms the same basic point later in the speech in the paragraph concluding with ‘strive for the kingdom of God and its justice, and all these things will be given to you as well’ (Matt. 6:25-33).”((Horsley, Covenant Economics, 153.))

For Jesus’ followers, these beatitudes would be heard as recognizing and emphasizing their lived experience of injustice and impoverishment.

The Sermon on the Mount continues by addressing problems of inequality and mistreatment of community members. It encourages the leadership of the poor and oppressed, as we can see in the imperative to the peasant disciples to let “their light shine” (Matt 5:9-16). Matthew 6:1-18 emphasizes resistance to hypocrisy with regard to three religious and social practices in particular: almsgiving, prayer, and fasting. Jesus critiques the “hypocrites” for sounding a trumpet in the synagogue and on the streets when they give to the needy (6:1-4), for praying in public so everyone notices (6:5-15), and for looking somber in order to get attention when they are fasting (6:16-18). In other words, the hypocrites give alms, pray, and fast to be glorified by others rather than to glorify God; such elevating of the self follows the hierarchal pattern of the empire and not the mutual solidarity and good news for the poor required in God’s Kingdom (as is told in Matt 4:23, 9:31, 11:2-6, 19:16-26, 25:31-46).

Although these three instructions (on giving to the poor, fasting as religious observance, and praying to God) are requirements for all Jesus-followers, the instruction of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount is to recognize the potential dangers of propping oneself up (on the backs of others) and, by extension, of propping up the hegemonic system that impoverishes and exploits the many. Jesus’ instruction and warnings on the perils of a self-serving approach to these three practices are linked to his seven woes to the hypocrites in Matt 23. Jesus critiques those who oppress others, use people for their personal favor and benefit, forget the things that matter like justice and mercy, and look shiny on the outside but are shallow on the inside. He is concerned with doing justice, not with paying action-less lip service to it while blatantly committing acts of injustice (as seen in Matt 21:28-32, 25:31-46). This emphasis on praxis in Matthew, the combinations of words and actions, is a renewal of the teachings of ancient Israelites’ Mosaic covenant and prophetic traditions.

The hypocrites give alms, pray, and fast to be glorified by others rather than to glorify God; such elevating of the self follows the hierarchal pattern of the empire and not the mutual solidarity and good news for the poor required by God’s Kingdom.”

In addition to the Sermon on the Mount, there are a few parables (another major form of Jesus’ revolutionary teaching) unique to Matthew that also reaffirm the focus on instruction and economics, including the Parables of the Weeds (13:24-30, 13:36-43), the Hidden Treasure and Pearl (13:44-46), the Net (13:47-50), the New and Old Treasures (13:51-52), the Laborers in the Vineyard (20:1-16), the Two Sons (21:28-32), and the Ten Bridesmaids (25:1-13). What is particularly important to highlight here is the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard (Matt 20:1-16).

For many, this parable is confusing. Workers go out to work and make an agreement with the farmer to receive one denarius, the standard rate for day laborers. When some workers start their work hours later, they are still paid the daily rate. These “undeserving” workers earn money for work they do not do. This represents an economic logic where God provides and people do not have to worry about (or prove that they deserve) their daily needs. This could be an echo of the manna story in the Exodus narrative (Exod 16:1-22) or the teaching on the lilies of the field from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 6:25-34). Perhaps this parable shows the difference between the Roman greed-based money economy and the need-based economy of God that Jesus teaches to his followers and is held up (maybe even practiced) by the Matthean community.

Another important parable in Matthew is the Parable of the Talents/Pounds. In this story slaves are charged with keeping sums of money secure for their master. Two of the slaves invest the money, doubling and tripling it, and are lauded and rewarded by their master. The master is very harsh on the last slave, who does not invest his money, and damns him to hell or at least a very harsh and short life. In fact, this last slave calls the master out as a harsh man who “reaps where he doesn’t sow” and takes what is not his. We can apply the work of Luise Schotroff and William Herzog to this parable and see it as an example of a “parable as subversive speech,” used to shed light on the reality of life for the poor and dispossessed during the Roman Empire.

Viewing this parable as a story that puts into full view the exploitation and exclusion of the poor majority in the Roman Empire, it becomes a part of a larger and broader critique of usury, investment, and money-making emphasized by Jesus and present throughout the Bible. Indeed, activities that violate Torah stipulations (Lev 25:35-38; Deut 15:7-11), such as banking, trading, investing, and making outrageous profit (usury), pervade the language of these parables, contributing to an understanding of the gospel as an uncompromising critique of these economic practices. Throughout Matthew, there are economic turns and twists—places where Jesus teaches and/or demonstrates that the economy of God’s kingdom is not what we are used to, and not always what we would expect.

Jesus’ Revolutionary Economic Program

In both Matt 9:9-13, where Matthew is called to follow Jesus, and Matt 10:3, where he is listed as the eighth disciple, we learn that in addition to being a learner/disciple, Matthew is a tax collector (telones). This detail should not be overlooked, especially in a reading focused on wealth, poverty, and economic justice. Tax collectors were retainers for the Roman Empire and the local provincial elites and many of them acquired wealth for themselves as well:

“Rome took about 12 percent as a land tax, a denarius head tax on each member of the household, and a wave offering about 1/40th of the harvest, for a grand total of 15 percent. Add to this the 20 percent of the harvest set aside for sowing the next crop, and the peasant household is left with 65 percent of their subsistence crop, 55 percent if they tithe to the Temple and 45 percent if they pay a second tithe.”((David Fiensy, Social History of Palestine (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1991), 103.))

The taxes were collected through the Temple, so the high priest was also involved in this system of taxation.((Edward J. Carter, “Toll and Tribute: A Political Reading of Matthew 17.24-27,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 25:4 (2003): 413-431.)) The fact that the namesake for the Gospel of Matthew is someone who gives up collecting taxes for himself and the empire to follow the teachings of Jesus should serve as further instruction on covenant economy and economic practice for Matthew’s community; Jesus’ follower, Matthew, transforms debt and taxation for Caesar into discipleship and justice for God.

In his book, Covenant Economics, Richard Horsley writes:

“Matthew’s Gospel, moreover, expands Jesus’ condemnation of the rulers of Israel for their economic manipulation and exploitation or the people, all clearly on the basis of covenantal commandments and principles (17:24-27; 21-22; 23) . . . Matthew also indicates that the communities addressed understand themselves as a continuation of the renewal of Israel inaugurated by Jesus over against the rulers of Israel, the high priesthood in the Temple as well as the Romans.”((Horsley, Covenant Economics, 150-151.))

It is important, therefore, to explore a few special teachings and actions in Matthew, which illustrate the notion of Jesus the social movement leader with a revolutionary economic program.

In Matt 17:24-27, Jesus and Simon Peter discuss the Temple tax. In this story, Jesus reminds Simon Peter that when collecting taxes, rulers usually tax others, not their children, and asserts that the children of God should therefore be free. He then instructs Simon Peter to catch a fish, take a coin out of its mouth, and use that coin to pay for both Jesus and Simon Peter. Since the taxes they pay end up coming from a fish in the sea, this instruction may show how taxes are taken from the hard work of the inhabitants of the empire, including especially fishermen in Galilee and the ports of Antioch.

Their joint payment of the Temple tax could also be seen as a public act of tax evasion and nonviolent direct action. Since the temple tax was a head tax, each person was required to pay individually. In front of others, Jesus is refusing to pay the Temple tax—or saying that Simon Peter’s payment should count for him, too—and asserting that the children should be free. He acts out a new reality while critiquing the current reality and system, where only the poor pay taxes and the elites—through nepotism and their political and economic power—pay little compared to what they have and in some cases actually make money from other people’s taxes.

Then, in Matt 22:15-22, the topic of taxes is raised again. The Pharisees try to trap Jesus by asking if they should resist paying the imperial tax, to which Jesus makes a famous reply: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Throughout its history of interpretation, this passage has been used to justify subservience to Caesar, the empire, and therefore the state. Much like the role that “the poor will be with you always” has played in justifying poverty, this pericope has been used to argue that religion and politics be kept “separate”, and that those with political power shouldn’t be scrutinized and critiqued by the church. But rather than the separation of church and state or the moral condoning of dictatorship and state sponsored repression of the people (like in El Salvador and other parts of Latin America where this passage has been used), this passage may be actually critiquing those in power and claiming that God condemns this sort of violence and repression.

In this story, Jesus knows the Pharisees have set a trap and asks them to take out a denarius and look at it. He suggests that because the coin has Caesar’s head on it, they should give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar. He also says that they should give to God what belongs to God, thereby reminding everyone that God’s mark is on all creation and requires one’s whole heart, mind, and soul. Rather than justify dispossession and submission to authority, this statement on Jesus’ part serves as a subtle but sweeping critique of Caesar as being less important and vast than the God of Israel.

“Jesus’ follower, Matthew, transforms debt and taxation for Caesar into discipleship and justice for God.”

In this passage, Jesus may be limiting Caesar’s power and authority to money (by stating that since Caesar’s head in on the money, money is the realm of the emperor). He may also be suggesting that all the things that humans need to survive—air, water, food, shelter, etc.—are creations and gifts from God, and should therefore not be controlled by Caesar or any other human being who can lord that control over others.((Warren Carter, “Paying the Tax to Rome as Subversive Praxis,” 9.)) Also, by asking the Pharisees to pull out a coin, Jesus purposely calls attention to the access to resources they have, as apologists for the Roman Empire, contrasting it with the poverty of Jesus and his followers.((Herzog, Teacher and Prophet, 182-185.))

In addition to special instruction on taxes, there are new economic practices present throughout Matthew that fit into the portrait of Matthew as a reformed tax collector and social transformer. The Sermon on the Mount includes pronouncements on not storing up treasures on earth and also not worrying about one’s basic needs because God will provide. In Matt 6:25-34, Jesus suggests that humans, including his disciples, should not worry about food, shelter, or clothing, saying that worrying does not add time to one’s life.

Jesus reminds his followers that God protects and looks over everything in nature. These teachings perhaps even remind the Matthean audience of God’s liberating action from slavery and the manna story in Exodus 16:1-36, where God’s people are to take what they need (Exod 16:16, potentially parallel to not storing up treasures in Matt 6:19) because any excess will ruin and be spoiled by maggots and worms (Exod 16:20, potentially parallel to treasures rusting, rotting, or being stolen in Matt 6:20-21), and to trust in God who will provide for your survival and thriving (not Pharaoh or other emperors who claim to be gods).

Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount also includes the Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:9-15) and emphasizes material needs like having daily bread and debt forgiveness (the Greek term ofeilēmata, meaning “debts,” is used in Matthew where hamartia, meaning “sins,” is used in Luke 11:4), the coming of a new kingdom/empire, the making of earth to be like heaven (which only occurs in Matthew, not in Luke), and rescuing the supplicants from the evil one (which also only occurs in Matthew, not in Luke). Indeed, the prayer that Jesus teaches all believers to practice focuses on forgiveness of debts, meeting material needs, resistance to oppressors, and economic justice on earth. It is a direct critique of earthly empire and rulers and how these powerful people indebt and dispossess the majority.

The Sermon on the Mount also states that you cannot serve both God and Mammon (Matt 6:24). This passage is central to Matthew’s Gospel and the overall message about money, wealth, and idolatry. The instruction is clear: Jesus’ followers must choose between God and money and to choose money is idolatry (cf. Exod 20:1-26). These passages from Matthew show us that a key focus of the Gospel is alternative economic practice and subversion of the economy of empire. Jesus’ followers are to forgive debts, be provided for even when undeserving, possibly even evade and protest taxes, and not worry about or give authority to a Lord who impoverishes, but worship the one Lord and God who provides for all, including the poor. Jesus will lead the way.

Not Blame, Not Pity, but Power

I have tried to pull out some important passages and points from the Gospel of Matthew about the revolutionary program and teachings of Jesus. There is much more to be said and studied. In order to argue against the assumption that poverty is not a major issue in Jesus’ day or accepted as unfortunate but still inevitable by Jesus, we must explore the breadth and depth of poverty in the Roman Empire and Jesus’ challenge to it. We must also study poverty and dispossession under twenty-first-century capitalism and its neoliberal policies. My own study suggests that capitalism, along with the system of philanthropy and charity that upholds it, actually spreads and deepens poverty and inequality. It also tells me that today we need a social movement of the poor, one that challenges the polarization of wealth and poverty and posits that a new world without poverty, inequality, and economic insecurity is possible.

Attention to historic and contemporary context, especially the demographics and causes of poverty, demonstrate that rather than individual problems, poverty and dispossession are social problems affecting the whole society both in Jesus’ time and today. I have attempted to argue that Jesus was a leader of a social, economic, political, and spiritual movement led by those at the bottom of the Roman Empire who united across nationality and religion to promote dignity, prosperity, and justice for all people. Jesus’ words and actions, as documented in the story of the “Anointing at Bethany” and throughout the Gospel of Matthew and the New Testament, can be seen as instructions for the poor to unite and organize today to transform society and end poverty for all. Therefore the ideas that poverty in the Bible is a spiritual condition and the that poverty will end only in heaven cannot hold.

This article grows out of the intensity of poverty and dispossession in contemporary America and the urgency of poor people’s efforts to build a movement to end poverty. Preacher, professor, and Poverty Initiative leader Barbara Lundblad suggests that faith is key to this endeavor: a belief that ending poverty is possible, an understanding that this is what God requires, and a conviction that this is how Christians must act out their commitment to Jesus.

“Do we need more statistics? More courage? More time to volunteer? Perhaps most of all we need more faith. Jesus’ parable [on the rich man and Lazarus] ends with these ironic words: ‘Abraham said to the rich man, ‘If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.’’ Someone has risen from the dead. What more do we need?”((Barbara Lundblad, “Closing the Great Chasm: Faith & Global Hunger Part 2” n.p..))

But instead of developing the faith that ending poverty is possible, we ignore the controversial, revolutionary nature of a poor, resurrected Jesus as Lord and Savior, who challenges the wealthy, immortalized Caesar. We forget that Jesus’ Kingdom is about economic and social rights in the here and now and that the messiah Jesus came to usher in this reign. The good news of the Bible has been reduced to an individualized acceptance of Jesus Christ as a Lord and Savior, severed from his mission to the world. And even that mission has been hollowed out by selective and superficial quotation, reduced to a patronizing and charity-centered care for the poor that leaves the structures of oppression and exploitation intact. We deny that the poor are God’s people and are at the center of God’s concern, and ignore that Jesus was a leader of a revolutionary movement of the poor who, rather than mitigating the unfortunate, inevitability of poverty, called for a movement to transform heaven and earth.