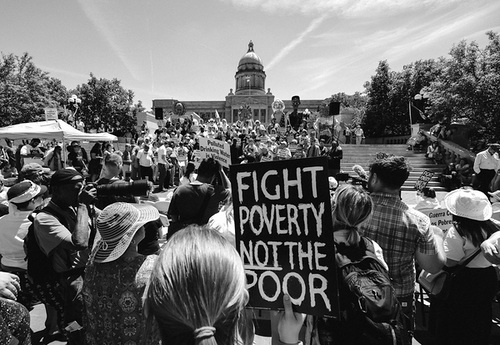

As we have been saying in the Poor People’s Campaign, poverty is a policy choice. There are policies and programs that we know can lift the load of poverty. The fact that poverty exists reflects a political failure, rather than any fundamental scarcity of resources that can be used to end poverty.

The Child Tax Credit (CTC) is a stunning example of poverty being a policy choice. When the CTC was expanded through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) early in 2021, families began receiving monthly advance payments by July, which had an immediate and positive impact on poor children and families. In fact, according to the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy (CPSP), 3.7 million children were lifted above the poverty line as a result of these payments.

When the payments ended in December, those 3.7 million children once again fell below the poverty line.

This did not need to happen. There was no budget crisis or other resource scarcity that prevented the government from continuing these payments. Moreover, our government had just agreed to spend over $770 billion on the Pentagon. These payments ended because Republican lawmakers and some Democrats held back the Build Back Better agenda in the Senate.

This policy briefing focuses on the CTC, looking at its history, what happened with the expanded CTC in 2021 and why it matters for our welfare programs more broadly.

When the payments ended in December, those 3.7 million children once again fell below the poverty line.

This did not need to happen. There was no budget crisis or other resource scarcity that prevented the government from continuing these payments.

A Brief History of the CTC

The CTC was first enacted in 1997 as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act under President Clinton. At the time, it created a $400 tax credit per child (under age 17). In 2001, it was expanded to $1000 and then to $2000 under President Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

The 2017 tax law, however, denied this full expansion to poor and low-income households in at least the following ways:

- It placed a $1400 cap on the refundability for low-income households. This meant that these households only received at most a $400 increase in their benefits per child, rather than the $1000 increase that higher-income families received;

- It ended access to the CTC for children without social security numbers, who were overwhelmingly undocumented children; and,

- The refundability formula did not allow families with earnings less than $2500 to receive any of the credit at all.

Otherwise, the basic structure of the CTC stayed the same through these changes. For middle- and higher-income households, it directly reduced their tax burden based on the number of qualifying children. For example, if a household with two qualifying children owed $4600 in taxes without the credit, the CTC reduced their taxes by $2000 per child, leaving them with only a $600 tax liability. (Read this article from the Economic Policy Institute to see how this is different than indirectly reducing taxable income.)

The CTC, in fact, privileged higher-income taxpayers and households, whose tax burdens were often greater than the full amount of the credit. Families whose incomes were less than the full amount of the CTC were only eligible for part of the credit, which they received as a “refund.” After the 2017 tax cuts, the amount of the refund was based on 15% of household earnings above $2500, up to $1400 per child. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a single parent with two children who earned $14,000 – and whose tax burden would not offset the full $2000 per child credit – could receive a refund of 15% of their income over $2500. This comes out $1725 ($11,500 x 0.15). Yet, a single parent with two children earning a higher income would be eligible to receive the full $4000 credit ($2000 per child).

Meanwhile, because the CTC was structured around taxes, households that were too poor to pay taxes could not access any of its benefits. They had no basis against which the credit could be applied. Of course, by definition, households without any children were also excluded.

Unlike the CTC, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) was designed to be more targeted towards low-income households, including that it is fully refundable. In other words, it is still available to workers who don’t owe any taxes. According to the Economic Policy Institute, “the EITC was supposed to be a temporary refundable tax credit for lower-income workers to offset the Social Security payroll tax and rising food and energy process…[it] was considered both an anti-poverty program and an alternative to welfare because it incentivized work.” As income increases, the worker or household is eligible to receive more and more of the benefit, until, however, their income reaches a certain threshold. Then, the benefit steadily declines.

In 2019, a married couple with two children could receive the full EITC benefit so long as their household income was under $25,000. This was just under the official poverty line that year. After that threshold amount, the benefit decreases with every additional dollar earned. Once their household income reaches $52,500, or just over twice the poverty threshold, they were ineligible to receive any of the EITC’s benefits. It is also available to workers without children, although the benefits are far less.

Although these policies have been shown to reduce the numbers of people living below the poverty line, they reveal the real limits of using tax policy as welfare policy: the CTC excluded the poorest families, the EITC was only accessible so long as households earned poverty wages and those with little or no earnings did not receive any significant support. Households that fell between 100% and 200% of the federal poverty line – including many of the 140 million who live within that precarious margin above the poverty line, but one emergency away from economic ruin – received less and less of its benefits.

Finally, not only did these tax policies prioritize working households, they were oriented around having children, rather than addressing poverty in and of itself, reflecting deeply embedded beliefs about who is deserving and undeserving of receiving social welfare.

What Happened in 2021

In 2021, the CTC and EITC were dramatically improved by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). As the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia summarized, the CTC was changed in three significant ways:

- Benefit levels were increased from $2000 per child to $3600 for children under 6 and $3000 for children between ages 6-17;

- It was made fully refundable and therefore accessible to families who had otherwise been too poor to receive the credit in the past; and

- Rather than being paid out as an annual credit or refund, beginning in July 2021, benefits were paid out in monthly installments of $300 for children under 6 and $250 for children between ages 6-17.

Changes were also made to the EITC, to lend critical income support to over 17 million low-wage workers without children, including:

- Raising benefit levels for workers without children from $540 to $1500;

- Raising the income cap for these workers from $16,000 to about $21,000; and

- Expanding the age of eligible workers without children to younger workers (ages 19-24) and workers older than 65.

Many of the changes had been called for by welfare rights organizers, anti-poverty organizations and policy experts for years. And, as the CTC’s monthly payments went into effect in July, their effects were immediate. The first payments reached over 59 million children, or approximately 80% of all children in the country, including, for the time, the poorest children in the country. In just one month, child poverty rates fell four percentage points (from 15.8% to 11.9%) and 3 million children were moved above the poverty line. (Note: These 3 million children were living under 100% of the poverty line, and may have been moved to the 100%-200% threshold, and therefore still counted among the 140 million people who live under 200% of the poverty line. The impact of the CTC on children living under 200% of the poverty line is less than the impact of children living under 100% of the poverty line, but significant nonetheless.)

By December, over 61 million children in more than 36 million households had received CTC payments. Roughly 3.7 million children were moved above the poverty line. Notably, although more white children were moved above the poverty line overall (1.37 million), poor Black and Latino children experienced their greatest benefits, with a 6.6 and 7.2 percentage point reductions in their poverty rates, or 737,000 and 1.35 million children, respectively.

Many of the changes had been called for by welfare rights organizers, anti-poverty organizations and policy experts for years. And, as the CTC’s monthly payments went into effect in July, their effects were immediate. The first payments reached over 59 million children, or approximately 80% of all children in the country, including, for the time, the poorest children.

Speaking to the effects of the expanded CTC to address the racial inequities of poverty, Sophie Collyer, Research Director at CPSP, said during a phone call, “this is an example of a program that worked on multiple levels.” In fact, according to the Center on Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), most of the decline in poverty rates overall in 2021 – and not just child poverty – were “driven by” the expanded CTC.

The Build Back Better Act (BBBA) would have extended these monthly payments into 2022. The House of Representatives passed BBBA in November, but once it moved to the Senate, progress came to a halt. Every Republican senator opposed the bill, leaving Democrats in a tenuous position of needing all 50 Democratic senators to vote in its favor. And then, the week before Christmas, Democratic Senator Joe Manchin broke rank by telling the nation he refused to support the bill on Fox News. Falling short of its 50 votes, the majority leadership decided not to call it to a vote, and the bill stalled.

Without a single CTC payment in 2022, child poverty rates have climbed back quickly, from 12.1% in December to 17% in January. This increase represents the 3.7 million children who had been moved above the poverty line in 2021 now falling back under it. The highest increases in child poverty have been among Black and Latino children (5.9% and 7.1%, respectively), with white children accounting for the greater number of children experiencing this decline (1.4 million). Given the impact of the CTC on poverty more broadly, CEPR anticipates that unless the expanded CTC is extended, “poverty will increase in the second half of 2022.”

New Proposals for the CTC

In March, President Biden signed H.R. 2471, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2022, an omnibus bill that allocates $1.5 trillion to fund government activity until this fall. More than half (over $780 billion) will go towards defense spending, with over $13 billion to Ukraine. As National Priorities Project director, Lindsay Koshgarian, recently wrote, “The budget deal announced today repeats a longtime pattern by putting more resources into the military and war than into K-12 education, affordable housing, public health, scientific and medical research, early childhood education and care, and homelessness combined…Even as war rages in Ukraine, a higher military budget can only risk a larger war; it can’t promote real solutions and alleviation of suffering through diplomacy and humanitarian aid.” The bill will also provide over $14 billion to Customs and Border Patrol, $8 billion to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and $600 million for Capitol police.

The remaining $730 billion going to non-defense spending priorities will cover housing programs and rental assistance, Head Start, SNAP, WIC, infrastructure investments, increased Pell grants and resources for Indian Health Services. A $15 billion pandemic aid provision was left out of the bill.

Due to ongoing resistance from Sen. Manchin and others, the CTC is also excluded from this bill. However, the fight for the CTC is not over. There are at least two proposals to both expand the CTC and implement additional changes to existing welfare programs, one from Senator Mitt Romney and another from Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Mondaire Jones.

Sen. Romney’s bill is, essentially, the “Republican” version of the expanded Child Tax Credit. Administered through Social Services Administration (SSA), it would bring back direct monthly payments of up to $350 per child and is fully refundable. This sounds promising, but it would also make massive changes to current social welfare programs and the tax code by: fully replacing the current CTC, ending Head of Household filing status, ending the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, and partially replacing the EITC; ending federal funding for TANF, our predominant welfare program; and making major cuts to SNAP. According to Jim Pugh, founder of Universal Income Project, “The ripple effects of bumping people off benefits they already automatically receive through TANF eligibility would be really harmful.” Even though our welfare system is beleaguered with inefficiencies, it is unclear if this allowance would fully replace or even decrease the assistance that is currently received through these other programs.

Further, Romney’s proposal hinges on work requirements, which have been repeatedly shown to unduly punish poor and low-income households and are likely to severely curtail access to these payments. As such, it suffers from the insidious belief that people are poor due to their own failings, rather than addressing structural flaws in our economy that keep people poor.

The second proposal from Reps. Tlaib and Jones is better. The End Child Poverty Act (ECPA) implements a universal child allowance that is paid out by the SSA and replaces the current CTC, partially replaces the EITC and Credit for Other Dependents. However, the payments and replacements are tagged to our current poverty measures, which are notoriously low and outdated. (Both proposals are also limited in that they address child poverty rather than poverty more generally.)

Given the challenges of securing bi-partisan consensus around the expanded CTC from 2021 (or really anything other than war), it is likely that Romney’s proposal gains more traction in the coming months than the ECPA, especially as poverty rates climb back up. (Under the provisions of the 2017 Tax law, the CTC will need to be reauthorized in 2025, so we can expect to hear more about it in the coming years.) If so, it may open up broader conversations around welfare reform for the first time since 1996.

Lessons from the National Welfare Rights Union

More than 50 years ago, the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) pushed back on a proposal from President Nixon that, similarly, would have taken away programs and payments from poor women and households. Although relatively new, NWRO had established a network of more than 700 welfare rights organizations across all 50 states. Due to their efforts, enrollment in Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) or welfare had nearly doubled from 4 ½ million to 8 ½ million from 1966 to 1970.

In a 1971 article in the National Black Law Journal, Executive Director of NWRO, George Wiley, described the profound impact of NWRO’s organizing: “Using militant direct action methods, welfare recipients won campaign after campaign: for school clothing, furniture, special diets, winter clothing, free school lunches, simpler and fairer procedures, speedier treatment and higher welfare grants in many states. At the same time, legal attacks were striking down man-in-house rules and durational residence requirements, establishing privacy and eliminating many of the arbitrary practices and multiple standards where welfare recipients are judged by different criteria of law than the society at large.” As a result, AFDC’s allocations more than doubled in just a few years, to meet the needs and demands of its recipients.

These gains (especially among poor Black women), Wiley continued, unleashed an outcry among the political elite and “precipitated a national debate concerning the ills of the welfare system.” In response, President Nixon released a Family Assistance Plan (FAP) that was aimed at “getting everyone able to work off the welfare rolls and onto payrolls,” insisting that instead of welfare, America needed “workfare.” The plan put forward a guaranteed income floor, alongside a forced work program that would require recipients to accept whatever wages and work conditions were offered to them through the relevant administrative agency.

NWRO adamantly opposed the FAP for several reasons: the income floor was pegged to an inadequate poverty line and less than one-third the costs of basic necessities; it didn’t account for regional variations in costs of living; and the payments were less than the current payments that the vast majority of welfare recipients were currently getting. The work requirements also suggested that care and housework were not real work or concrete contributions to society, thereby dividing the poor into who was “deserving” of federal assistance and who was “undeserving,” based on their ability to work outside the home. Rather than benefiting the poor, Wiley described the FAP as a welfare program for employers, who would thereby secure a “supply of cheap labor.”

NWRO launched a full-scale attack on the FAP, including lobbying members of Congress to vote against it in the Senate Finance Committee, and ultimately defeated it. They also developed their own proposal that included: cash assistance that phased out at higher levels to ensure adequate incomes and a decent standard of living; direct payments to caregivers; simpler eligibility requirements; and the meaningful participation of recipients in decisions on policies and regulations that impacted their lives.

Welfare is Worth it

At its core, NWRO’s proposal was organized around the principles of dignity, justice and equity so as to end poverty, rather than entrench it. It insisted that poor and low-income people did not need to prove their worthiness to receive government assistance. Rather, it was the responsibility of our society to establish programs that would redistribute social wealth and end poverty.

The expanded CTC carried forward many of these same principles: full refundability reached the poorest households, even if they didn’t pay taxes; although imperfectly administered, the monthly payments provided regular and direct support to millions of families – poor, lower-income and even middle-income – without any questions asked; and they all received the same amount. This allowed us, for a few months, to see the true extent of the need for these payments, including among low-income households, even though they are not typically included in many of our anti-poverty programs.

At its core, NWRO’s proposal was organized around the principles of dignity, justice and equity so as to end poverty, rather than entrench it. It insisted that poor and low-income people did not need to prove their worthiness to receive government assistance. Rather, it was the responsibility of our society to establish programs that would redistribute social wealth and end poverty.

Moreover, new research from CPSP estimates that these payments could have society-wide benefits: “Converting the current Child Tax Credit to a child allowance—by making it fully refundable, increasing its value to $3,600 per child age 0-5, $3,000 per child age 6-17, and distributing it monthly—has a gross cost of about $100 billion, a net cost of only $16 billion and generates about $800 billion in benefits to society.”

These findings show that poverty is the drag on our economy, not welfare. Indeed, some of the lessons to be learned from the expanded CTC are that:

- Direct cash payments and transfers can reduce poverty and economic insecurity;

- These payments are most effective when they are in addition to other anti-poverty programs, like TANF, SNAP, and the EITC, i.e., no single policy or program can address decades of bad policies; and,

- While the CTC provided a temporary cushion against further economic decline, households need more support to relieve their deep economic insecurity. This was evident when child poverty rates quickly rose just one month after the CTC payments came to an end. To move households out of that insecurity, we need long-term policy commitments that are designed to do so, including for households without children.

In other words, rather than shrinking our welfare programs, we must dramatically expand them. As we have seen with the CTC, and pushback against it, this will not happen on its own, or from the goodwill of elected officials. We need a contemporary welfare rights movement – of poor and low-income households of all sizes and make-up, low-wage workers, housed and unhoused people, the uninsured and the underinsured, and many, many more – to advance a new welfare rights paradigm, to ensure that we all fare well.