Water is a basic human need and a fundamental human right. Yet, our access to water is increasingly restricted by extreme weather events, pollution, privatization and other consequences of a society that does not protect or respect this fundamental right. As a result, in a world that is two-thirds water, almost two-thirds of the world’s population regularly face water insecurity.

In the US, the water crisis is emerging first and worst as a crisis of affordability among poor and low-income communities. From 2000 to 2014, the combined price of water and sewage rose faster than the consumer price index. Alongside decades of stagnant wages, the proliferation of low-wage jobs and a $7.25 minimum wage, millions of people are unable to pay their water bills. Before the pandemic, it was estimated that 14 million households could not afford their water and that if trends continued, one-third of US households would be in the same situation. Water shut offs and disconnections were already taking place, with hundreds of thousands of people losing their access to water.

For several months during the pandemic, state and local governments instituted temporary moratoriums on these shut offs. However, without any federal action or legislation, these moratoriums have all expired and millions more are facing the risk of disconnections.

“I feel like my life has been violated and taken away from me because the simple fact of it is I can’t even bathe, brush my teeth, wash my hair, do the things people are supposed to do. This has been taken away from us. And it shouldn’t be.”

This is not a crisis of scarcity, but profiteering. The US has one of the largest sources of freshwater in the world, but we are in a battle over who has the legitimate right to that water – and our water utilities and services – with some of the largest corporations and financial institutions in the world. Their “water grab” is in inherent contradiction with our basic rights.

Fifty years ago, when Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was working with poor people’s organizations, religious leaders, students and others to organize the Poor People’s Campaign, he addressed this conflict: “One day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring. (All right) It means that questions must be raised. And you see, my friends, when you deal with this you begin to ask the question, “Who owns the oil?” (Yes) You begin to ask the question, “Who owns the iron ore?” (Yes) You begin to ask the question, “Why is it that people have to pay water bills in a world that’s two-thirds water?” (All right) These are words that must be said. (All right).”

Today, poor and low-income people across the country are saying the same thing. At a Poor People’s Campaign event highlighting the Jackson, Mississippi water crisis, Penelope Barnes said, “I’m a low wage worker. I am formerly incarcerated. Water is a human right. Clean water is a human right. I feel like my life has been violated and taken away from me because the simple fact of it is I can’t even bathe, brush my teeth, wash my hair, do the things people are supposed to do. This has been taken away from us. And it shouldn’t be.”

In September, the Kairos Center’s Policy Team talked with Mary Grant from Food and Water Watch (FWW), a national environmental organization, about our right to water. Mary is the “Public Water for All” Campaign Director at FWW and works with organizers at the local, state and federal level to protect water as a public resource and fight for safe affordable public water for all. She talked through the crisis in Jackson, Mississippi, and how it is the latest battleground in an escalating conflict around water. She also connected Jackson to a legacy of systemic racism, democracy and our right to participate in the decisions that impact our daily lives.

“There is a direct relationship between water and these attacks on our democracy. Our theory of change is about holding elected officials accountable and you can’t do that when people are disenfranchised….There have been state bills across the country to put water systems into receiverships, which takes all of the control over this basic resource and public asset away from the public…I’ve seen state legislation in North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey where legislators are trying to strip control of local water systems away from the public, in particular in majority black cities.”

Every crisis also presents an opportunity. Around water, poor people are organizing across race, issue, faith and geography to ensure that this basic right is protected and secured. Indeed, the Kairos Center is rooted in a theory of change that asserts poor people’s organizing is the way to ensure the whole of society has all of our needs realized and met. From water, food, housing and health care to quality public education, peace and democracy, poor people’s organizing has historically advanced and broadened access to these basic needs and rights.

Read more about what is at stake and how people are organizing in response, below.

***

Shailly Gupta Barnes: Before the pandemic, about 14 million households did not have access to clean and affordable water. This was in part because federal funding to local water systems has been on the decline for decades. Also, the privatization of water utilities has raised rates for users and households who are already facing increasing economic insecurity. What is the state of that water crisis today?

Mary Grant: The state of our water infrastructure is continuing to deteriorate. Water bills continue to grow beyond household ability to pay. Some estimates indicate that one in three households are struggling to afford their water bills. In a typical year, an estimated 15 million people experienced a water shut off.

To make things worse, the impacts of climate change are being felt very deeply and particularly in Black, indigenous and other communities of color. The people in Jackson, Mississippi, are still struggling without safe, reliable water and were under a boil order from July through September. And now their governor, Tate Reeves, is calling for privatization of the water system, against the wishes of the mayor of Jackson, Chokwe Lumumba, to open the local water utility for corporate exploitation.

SGB: Is the privatization scheme similar to what happened in Flint and Detroit?

MG: Yes, the situation is. The governor just announced that they were in conversation about privatization, but also state receivership – similar to the state emergency manager takeover that prompted the water crisis in Flint – and regionalization, which is how Detroit lost control of its regional water treatment system during bankruptcy. In Detroit, the emergency manager sent the city into bankruptcy, bypassed the city’s charter, which gave voters the right to decide the future of their water system, and seized the treatment systems to hand over to Detroit’s majority white suburbs. All three of these options – privatization, receivership and regionalization – are on the table in Jackson right now. And the governor might do any combination of them: put the water utility into receivership to force it into regionalization while privatizing it. That would be probably the worst-case scenario.

SGB: You’ve also shown when water systems are privatized, the rates go up significantly for an average household, so privatization isn’t a real solution to water affordability. How are these negotiations allowed to move forward, even though common sense and experience show that they do not solve the problems at hand?

MG: Private water companies charge 59% more than local governments for the same amount of water.

However, how this narrative is often framed is around “underinvestment” in infrastructure, with the blame always directed towards the local government not making investments that need to happen. This is problematic for a few reasons. First, it absolves the federal disinvestment that has been ongoing for decades. Federal funding for water infrastructure was at its highest in the late 1970s. The Reagan administration cut back funding dramatically and phased out the wastewater construction grant program, replacing it with a loan program. Since then, it just hasn’t been funded at the level it needs to be. Even though the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law provided a big increase to water infrastructure funding – about $50 billion over 5 years – that’s only 7% of the identified need around the country, just so far short of what is actually needed. (For comparison, the Clean Water Act of 1977 provided about $175 billion in today’s dollars.)

Second, water rates are already incredibly unaffordable in Jackson. They just don’t have the rate base necessary to support necessary improvements – you can’t just keep raising rates on households that can’t afford to pay their bills.

Third, the core of the issue is about white flight from urban centers. Really, the story of Jackson is not just about disinvestment or climate change. It’s about Jim Crow and legacies of oppression and systemic racism. Cities like Jackson (but also Detroit and Baltimore) were built up to support a larger population that doesn’t exist now. When schools were integrated, white people fled to the counties, leaving “stranded assets”: a city builds out a water system to provide safe water to a booming metro area, but when its service population declines, the city no longer has the customer base to support that system. A lot of the suburban white counties around Jackson have built their own water systems. It’s like how our schools are funded by the property taxes of the surrounding community. So wealthier areas have better funded schools than poorer neighborhoods, typically disparately harming communities of color. It’s the same with water systems.

Really, the story of Jackson is not just about disinvestment or climate change. It’s about Jim Crow and legacies of oppression and systemic racism.

And finally, these water systems are, for many cities, their largest capital assets, which is the real motivation for privatization. This fact rarely gets talked about.

SGB: Don’t we also hear that private enterprise will bring in more jobs, especially around infrastructure development?

MG: Yes, this is also being raised in Jackson, in particular around their workforce, which was overworked and understaffed at the water utility. In July, the workers there logged hundreds of hours of overtime. They even wanted workers to sleep there. They actually wanted to build a trailer right next to the wastewater treatment plant. They are dramatically understaffed, and this becomes another reason to justify privatization.

But privatization actually leads to more job loss. On average, one in three water jobs are lost after privatization. They are replaced with management from outside the community or contractors, which just isn’t sustainable for a city like Jackson. What Jackson needs is more of a job pipeline that trains and places local people in these jobs. There’s a really good model of this from Flint, where the plumbers’ union created an apprenticeship program to train local residents to help replace the lead pipes after the city got an infusion of federal money from the pandemic.

SGB: What is the relationship between our ability to access clean and affordable water and our participation or access to democracy?

MG: There is a direct relationship between water and these attacks on our democracy. Our theory of change is about holding elected officials accountable and you can’t do that when people are disenfranchised or you’re not providing a pathway to citizenship for immigrants. You don’t have that ballot box accountability. There have been state bills across the country to put water systems into receiverships, which takes all of the control over this basic resource and public asset away from the public. The fight over who controls our water systems is fundamental to the quality of our daily lives.

I’ve seen state legislation in North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey where legislators are trying to strip control of local water systems away from the public, in particular, in majority black cities. Flint and Detroit were put under emergency management – and under receivership – by a majority white state legislature.

In Flint, the emergency manager transferred millions of dollars of water revenue out of the city’s water fund over to the general fund. This contributed to massive rate increases in Flint. When the water crisis broke there, Flint residents had some of the highest water rates in the country. And that was a direct result of their loss of democracy and democratic decision making through the state emergency management law.

And in Detroit, the city lost control of their water system when it was forced into regionalization, which bypassed the city charter and the voters right to a referendum. This meant that the majority white suburbs had more control over Detroit water and wastewater treatment systems than the city’s majority Black residents.

And now in Pennsylvania, we’re seeing cities like Chester facing the threat of privatization of their well-run regional water system in order to pay down unrelated debt. Chester is under a state receiver, who has proposed using the water system to bail out the city budget. That decision-making is being stripped away from local government through these state laws that facilitate receivership and it’s disproportionately, almost exclusively, used on majority Black cities.

Tony Eskridge: Can you tell us more about what’s being done on the grassroots level and how communities are reclaiming their power, saying, “No. We know that privatization is not the way”?

MG: There are some important victories in lift up, yes.

In Atlantic City (New Jersey), an emergency manager was trying to privatize their water system, but the people there had studied what had happened in Michigan and were able to stop that effort.

And there’s a group in Pennsylvania called Neighbors Opposing Privatization Efforts (NOPE), who were able to get a contract rescinded in Norristown, Pennsylvania, in the suburbs of Philly. The contract would have sold their sewer system to a private company. Everyone thought it was a done deal, but NOPE stopped it.

Now they are working with their neighbors to prevent privatization in other counties. Just last week, there was a huge victory that they helped lead in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Bucks County had entered into a backroom deal with a private company, Central Aqua, for a $1.1 billion sale of its wastewater system. This would have been the largest privatization of a sewer system in US history. NOPE got people to attend meetings and rallies across multiple townships that would be affected by the sale, with tons of people showing up and contacting the county commissioner. Because of what they’ve heard from their constituents and the public, the county commissioner decided to end the deal. The largest sewer privatization in US history had been stopped directly because of public organizing on the ground.

The largest sewer privatization in US history had been stopped directly because of public organizing on the ground.

Investor analysts are saying the failed deal in Bucks County is a strong signal that the feeding frenzy of privatizing sewer and water systems in Pennsylvania is coming to an end. This is a model to replicate nationwide to stop this kind of privatization and maybe other forms, too.

We often see this kind of organic public opposition in communities wherever there’s a privatization deal. If community groups like NOPE can provide guidance to those efforts, they can hold these elected officials accountable.

TE: Thinking about Jackson again, what kind of pressures and threats is climate change placing on our water system?

MG: It really varies where you live and the time of year. In the western part of the United States, they are in a mega drought – a 1200 year historic drought. There are also pockets of drought on the east coast. But then there’s also too much water. Detroit was flooded this summer. Near historic flooding is what prompted in part the Jackson crisis as flood waters overwhelmed the treatment plant and put their pumps offline.

On top of that there’s wildfires, which can just destroy water facilities, but they can also contaminate water supplies, with all the ash that follows. There’s a town in New Mexico that had a little more than two weeks left of water, because wildfires contaminated their water supply.

And then we have hurricanes, like what happened in New Orleans, which destroyed key infrastructure and took their water systems offline for long periods of time. The wastewater systems in many parts of the country are not built to handle the levels of rain that they’re getting right now, which are a direct effect of the climate crisis. As sea levels are rising, water and wastewater facilities are being inundated completely and water supplies are experiencing saltwater intrusion.

In response, entire million-dollar wastewater facilities are being relocated – because of both rising water levels and falling groundwater levels. In California, there are hundreds of wells, both in households and in entire communities, that are going completely dry. These are usually farmworker communities, but right next to them, big industrial agricultural facilities are taking up their water. It’s also contaminating their water, which can be exacerbated during major flooding events, particularly after a drought. There’s even a threat of a hurricane hitting California this weekend, right after this mega drought. So it’s possible for all of these crises to hit at the same time.

Even though we’re not connecting all of these water disasters, investors are paying attention. In 2020, private investors launched the world’s first water futures market. In the summer, those water prices reached historic highs. Climate change and the climate crisis is creating all of this chaos and they’re looking at it in terms of how they can make money off of it.

SGB: What are you calling for in the Public Water for All Campaign?

MG: First, we are pushing for legislation like the WATER Act – Water Affordability, Transparency, Equity and Reliability Act – which would fully fund water and sewer infrastructure across the country at the level that it needs to be funded. What we need is $35 billion dollars each and every year, dedicated for communities and prioritizing disadvantaged communities first. This would be fully funded by increasing the corporate income tax rate by 3.5 percentage points. That’s all. This is well within the realm of possibility if we build that political will and hold our officials accountable and they do the right thing. This is possible.

SGB: And this would protect these assets from being put into receivership or becoming speculative commodities for Wall Street to invest in?

MG: Yes, restoring federal water funding would provide communities with the resources they need so that they can locally hold water systems as public trust resources. This could also help counter the affordability crisis and give these public water utilities resources to improve their water systems to make sure they are safe and climate resilient.

As we have seen repeatedly, people jump into action when their basic needs – like water – are threatened.

Second, Representatives Bush, Tlaib and Bowman have introduced a resolution that recognizes the human rights to water, sanitation, electricity, heating, public transit, and broadband communications. These public utilities are necessities. Although it’s just a resolution, we’re hoping to frame these essential utilities as human rights that cannot be denied to anyone, for any reason. The resolution outlines a framework and a path forward to guarantee utilities for all.

Finally, we are encouraging organizations like NOPE to keep building on the ground. As we have seen repeatedly, people jump into action when their basic needs – like water – are threatened. Of course, they are most effective when the city or local government still has control over its water system and can be held accountable to their residents.

This is what democracy is all about – being able to hold elected officials accountable to what we need – and why these groups are so important. They are actually fighting for democracy, because they know that once we lose that, everything is on the table, even our human right to water.

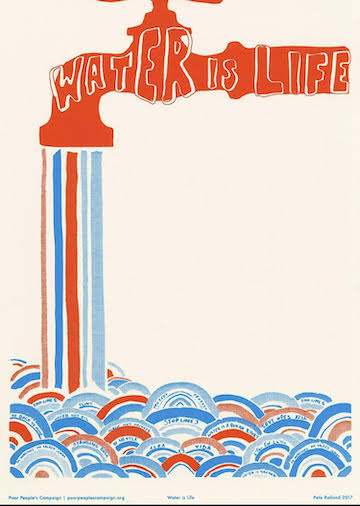

[Featured artwork: “Water is Life” by Pete Railand]