This policy briefing is based on an article published by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth in December 2022, “The Economic Impact of Housing Insecurity in the United States.”

For more information on the housing crisis, this new resource from the Kairos Center offers facts, testimonies, and cultural and theological resources on housing insecurity. Jointly produced by the Freedom Church of the Poor and Policy Team of the Kairos Center, it is intended to be a study guide for organizers and faith communities who are building a movement to end poverty.

Last November, I was in a conversation with people from across the state of Massachusetts who had gathered at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in Boston. Many of the people there were members and leaders of the Massachusetts Poor People’s Campaign. Rev. Savina Martin, a military veteran who helped lead the Boston Chapter of National Union of the Homeless in the 1980s and 1990s and a leader in the Massachusetts PPC today, spoke about the deaths they knew were coming as the bitter cold approached. Last year, she said, one of the churches piled up over 150 blankets to remember everyone they knew who had died in the streets.

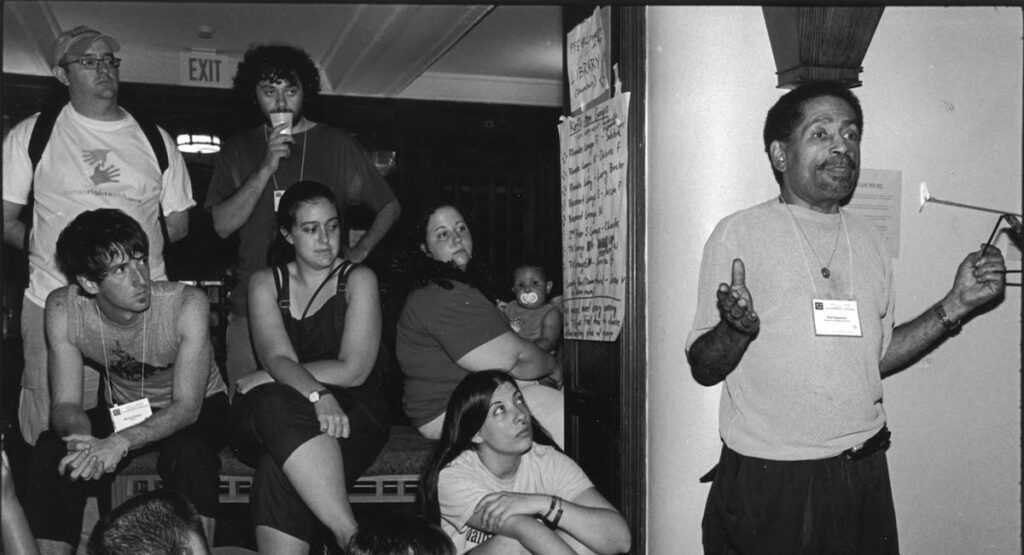

The National Union of the Homeless is a homeless-led organization of the poor. At its height, the Homeless Union had tens of thousands of members in dozens of states across the country. One of its key slogans was that they were “homeless, but not helpless,” an indication of their growing power and influence, which was rooted in their organizing among poor and unhoused people. That history continues to shape new generations of organizers, who are fighting to secure the human right to housing today. This policy briefing focuses on the housing crisis – from hundreds of thousands of unhoused people to millions of temporarily sheltered people to millions more who are one paycheck away from becoming homeless – and the insights and strategy of the National Union of the Homeless.

The Economic Impacts of Housing Insecurity

Homelessness is the most visible and jarring expression of housing insecurity in the United States, yet millions of people across the nation live in unstable housing conditions. These financially insecure people and families must often double or triple up with other people in housing designed for single families or single people. Many are living in their cars, outside encampments or temporary shelters. And many more are just one paycheck or one emergency away from losing their apartment or home.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were between 8 million and 11 million people who were unhoused or on the verge of becoming homeless. At the height of the pandemic, between 30 million and 40 million people were at risk of losing their housing. Many of them were protected by emergency pandemic measures such as rental aid, housing vouchers, expanded pandemic unemployment insurance, stimulus checks, the enhanced Child Tax Credit and a nationwide eviction moratorium.

These programs provided critical support for those struggling with housing insecurity during the COVID-19 recession. This, along with the legacy of years of low-wages and precarious work, without worker protections such as paid leave or health care, have all contributed to widespread financial fragility. Indeed, before the pandemic, there were 140 million poor and low-income people in the United States. Investments in our nation’s social infrastructure via pandemic-assistance programs brought these numbers down significantly, albeit temporarily, offering a glimpse of what a more equitable economy and society might look like—one where all workers and their families were treated as essential rather than expendable, where they could remain in their homes and living spaces and where child well-being was a national priority.

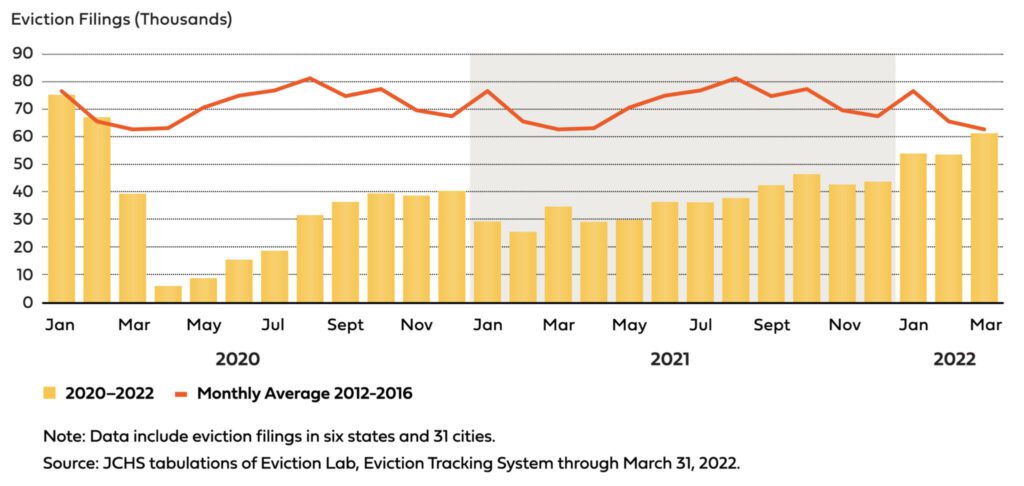

The eviction moratorium was the longest running of these programs, enacted first under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES Act in March 2020, and then extended by the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention multiple times. The moratorium was lifted in August 2021 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the CDC had exceeded its authority. Although the decision was premature and the Court itself acknowledged that between 6 million and 17 million tenants would be at risk of eviction. It nonetheless went forward, imposing this unnecessary trauma on millions of households. Evictions are now on the rise and may even surpass pre-pandemic levels.

According to a new study from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, rent increases for apartments reached record levels in 2022, with more than 75 percent of large metropolitan rental markets experiencing double-digit percentage growth in rental prices. These rising rental costs weigh heavily on poor and low-income households, especially historically marginalized households that do not have generational wealth upon which they could either fall back on or draw from to provide the financial resources to become homeowners.

The same study also documents that in 2022, lower-income households, renters, and homeowners of color were more likely to be behind in their mortgage and rental payments than other households. The latest Household Pulse data (December 9-19, 2022) shows that approximately 4.7 million households are behind on their home mortgage payments. More than 44 percent of these households (2.1 million) have an annual household income of less than $50,000. Nearly 20 percent of these financially stressed people (934,000) are Black, 15 percent (740,000) are Hispanic, 8 percent (413,000) are Asian American and more than 50 percent (2.4 million) are white.

The same Household Pulse data shows that among renters the numbers are worse, with roughly 13 percent of the nation’s renters behind on their rent—more than 7.5 million people. These renters are disproportionately Black (29 percent, 2.1 million) and Hispanic (23 percent, 1.8 million), although white renters account for 35 percent (2.7 million) of this population. Over 70 percent, or 5.2 million, are poor or low-income renters.

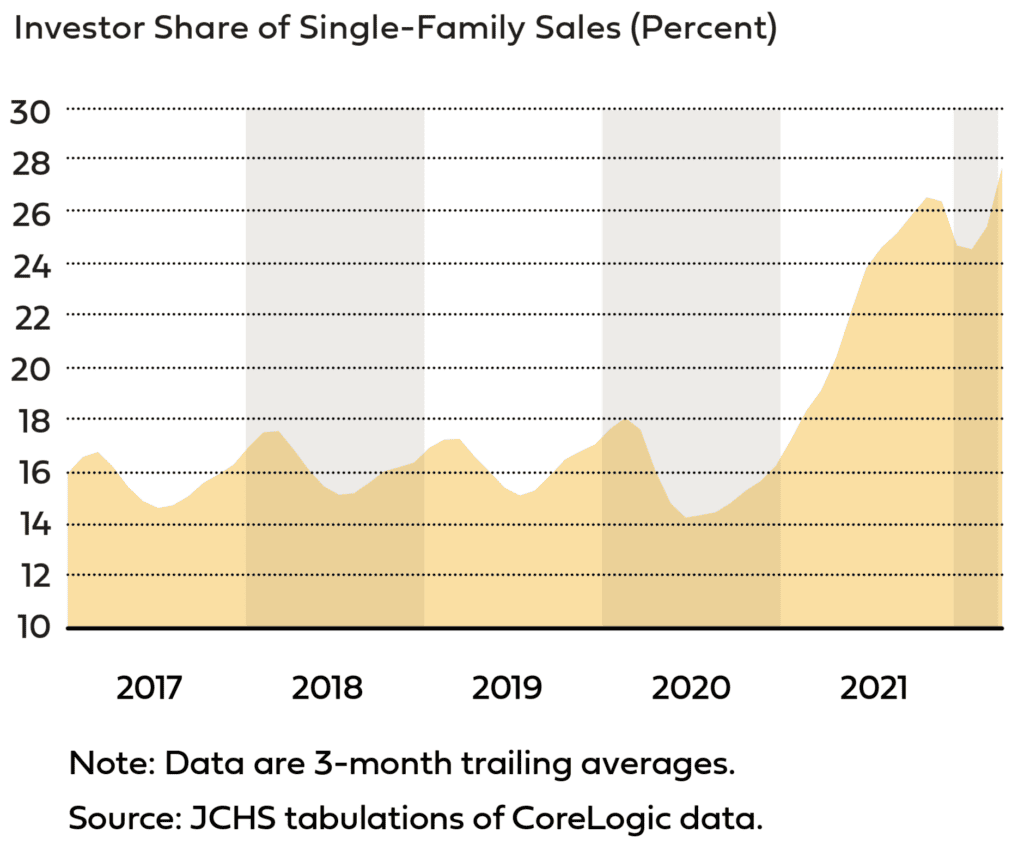

Part of this home mortgage and rental housing crisis is driven by the entry of Wall Street investors, particularly speculative private equity firms and hedge funds. Home purchases by these financial investors, which have been on the rise since 2008, spiked in 2021, contributing to these unaffordable rents and home prices.

What’s more, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in January that shelter prices are the dominant factor in the monthly increase in inflation in 2022. According to the BLS report, “The shelter index increased 7.5 percent over the last year, accounting for more than half of the total increase in all items, less food and energy.”

In short, housing insecurity is having an economy-wide impact.

The National Union of the Homeless—A History

Formed in the late 1980s, the National Union of the Homeless was a response to the emerging crisis of structural homelessness. In the 1970s and 1980s, major shifts in the global economy were accompanied by domestic policies that cut taxes for the wealthy, deregulated financial institutions, privatized public utilities and services and disciplined labor unions. These policies included massive cuts to affordable housing construction and assistance: from 1978 to 1983, the annual budget of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development went from $83 billion to $18 billion.

These cuts translated into a dramatic loss of affordable housing. Entire families were displaced and emergency shelter programs were opened to address the ensuing mass homelessness.

Those shelters became the recruiting grounds for homeless organizing. In 1985, more than 500 unhoused people and families founded the Philadelphia/Delaware Valley Union of the Homeless. The local effort quickly evolved into a national union, with 25 local chapters and nearly 30,000 members.

Importantly, the National Union of the Homeless brought thousands of people together across race, gender, sexual orientation, party lines, faith, geography and other lines of division.

At the founding convention of the Greater Boston Union of the Homeless in 1986, members passed a resolution that united unhoused people with “unemployed, under-employed, unwanted, and unnoticed people,” who were all suffering the injustice of poverty. It called for “young people, old people, black, white, yellow, red, and brown people, educated and uneducated people, people on welfare and people denied welfare, handicapped people, gay people, shelter and homeless people, men and women of all sorts of conditions,” to declare their solidarity with poor people everywhere. The resolution had specific prescriptions for housing, but also for jobs and job training, voting rights and public transportation. It declared that city surpluses and federal funds allocated to war be moved to meet these needs in Boston and across the nation. It expressed international solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. It was, in short, a call to restructure our whole society by ending poverty.

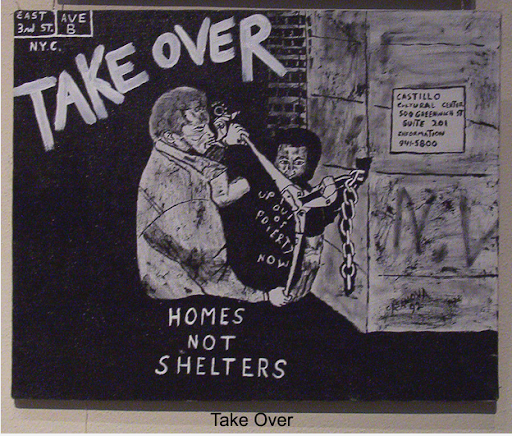

At its height, the Nation Union of the Homeless organized coordinated takeovers of vacant buildings across multiple cities owned and operated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, enabling unhoused people to move into abandoned, government housing to politicize their conditions. Ron Casanova, one of the founders of the NUH who lived and died on the streets, characterized these takeovers as a morally necessary response to legally sanctioned cruelty. Ending homelessness, he said, “can be done, if people take the initiative of breaking into these houses,” argued at the time. “Forget about it being against the law. I don’t care. Hell, I’m dying in the streets. That should be against the law.”

In a few short years, the National Union of the Homeless won the rights of homeless people to vote without an address, the creation of public housing programs run by unhoused people and commitments from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to make thousands of housing units available for the homeless.

Although the advocacy organization fell into demise by the mid-1990s—undermined by the crack epidemic, gentrification and internal strife—it was reconstituted in 2020. In just two years, the revived organization has established chapters across 11 states, a reminder that the crisis of homelessness is still raging.

Housing (in)security is a policy choice

As the housing crisis continues, cities and states have elected to criminalize homelessness: every state in the country has at least one city that has banned encampments or sleeping in public places, while Tennessee and Texas have banned encampments statewide.

However, there are policies that can relieve the pressures and trauma of housing insecurity without resorting to policing and incarceration. The answer to homelessness is housing. The answer to unaffordable housing is to make housing affordable through rent control, debt relief and living wages. In 2022, a true housing wage for a two-bedroom apartment would be $25.82 an hour, or about 3.5 times the federal minimum wage of $7.25.

These are some of the demands that have been made by the National Union of the Homeless and others to address the housing crisis and push back against street sweeps, rental evictions, and mortgage foreclosures. Alongside a growing network of homeless-led organizing, tenant organizing is gaining momentum, deploying creative tactics such as disrupting and blocking eviction hearings. Ballot initiatives for affordable housing, rent control and support for unhoused people are being passed in dozens of cities.

The Poor People’s Campaign has incorporated these experiences in its “moral policy” agenda, a broad-reaching document that articulates a concrete platform to establish a more equitable and just society. On housing, it calls for:

- The immediate cessation of all evictions and foreclosures, sweeps (of cars and encampments) and the criminalization of unhoused people

- An end to housing speculation, rent increases, and late fees on mortgage and housing payments

- An expansion of affordable, equitable and safe public housing (not government encampments or congregate shelters) for all in need—regardless of gender, citizenship documentation or carceral status, funded in part by profits unduly gained by the finance, insurance and real estate sectors of the US economy

- Relief from housing and rental debts

Many of these policies have an historic or contemporary basis to build from. Over the past two years there have been temporary or partial implementations of a number of these policies. They were proven to be effective then. They also ended too soon.

This is not unique to housing policy. The Child Tax Credit was indisputably effective in reducing child poverty, food insecurity and housing insecurity, especially among the poorest children and households (who are disproportionately Black and Latino). Yet, this program was also ended prematurely. Within weeks, nearly all of its gains were swiftly undone.

Rather than resource scarcity, these programs were cut due to a scarcity of political will, in particular the political will to prioritize poor and low-income people in our legislation and public policies.

Power for poor people

Although the solutions to poverty and housing insecurity are present, enacting these kinds of policies requires a steadfast commitment to ending the unnecessary injustice of poverty in the midst of plenty. It cannot be driven by charity, philanthropy or guilt, but a sense of duty, responsibility and accountability to the poor. In other words, it requires a profound solidarity with poor and dispossessed people to see our common humanity and to know that their insecurity reflects weaknesses and failures of our society that may very well impact my life – if not today, then tomorrow. Historically, these policies have only been enacted when those who are struggling against injustice organize themselves into a force powerful enough to move both the political will and social conscience in their direction.

When Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was working toward the launch of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, he recognized that building the political will for anti-poverty programs required organizing poor and dispossessed people—across race, issue, geography and other lines of division—to take action together. In Where Do We Go From Here, he wrote:

When people are mired in oppression, they realized deliverance when they have accumulated the power to enforce change. When they have amassed such strength, the writing of a program becomes almost an administrative detail. It is immaterial who presents the program; what is material is the presence of an ability to make events happen…our nettlesome task is to discover how to organize our strength into compelling power so that government cannot elude our demands.

At a meeting of poor people’s organizations in January 1968, King described that power in more detail: “Power for poor people will really mean having the ability, the togetherness, the assertiveness and the aggressiveness to make the power structure of this nation say yes when it may be desirous of saying no.”

The Kairos Center for Religions, Rights and Social Justice, which co-anchors the Poor People’s Campaign with Repairers of the Breach, has deep roots in poor led-organizing. From the National Welfare Rights Organization and the National Union of the Homeless to frontline organizing around housing, health care, water, public education, low-wage work, immigration and more, the Kairos Center has emerged out of more than two decades of groundbreaking struggle, dynamic liberation theology and engaged research and scholarship.

The Kairos Center recently collaborated with the reconstituted National Union of the Homeless for a “Winter Offensive” against poverty in the midst of plenty. From Thanksgiving to Martin Luther King Day, the Kairos Center and the National Union of the Homeless exposed the injustice of housing insecurity. When there are more empty housing units than there are unhoused people, the means are at hand to solve this problem. Armed with testimonies, facts, art, music and theology, the eight-week program reclaimed the true spirit of this season, insisting that a more equitable society is not only necessary, but possible.

As Jacob Butterly, a leader and musician with Put People First-PA, a grassroots organization organizing across Pennsylvania for health care as a human right said, “We can have healthcare and housing and food for everyone. There is an abundance for everyone. We just need the organization to get it.”