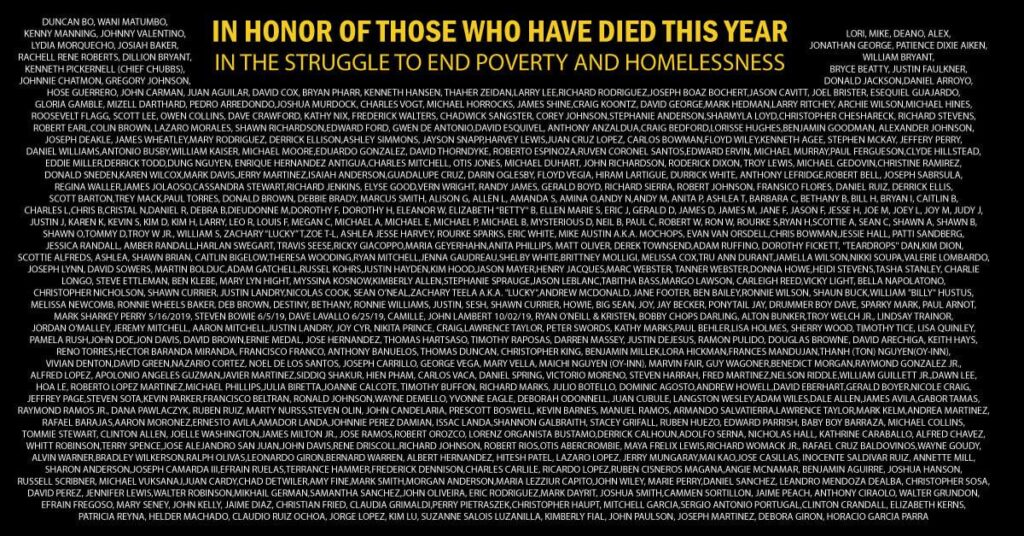

On December 21, the National Union of the Homeless (NUH) held a candlelight vigil in memory of those who have died homeless this past year. In just two days, they collected nearly 1000 names from local chapters across the country.

We, the people, call out the richest country in the world: How dare it have its people and its beloved sleeping in doorways, in bus stations, under bridges and living in shelters for life, in the midst of abundance.

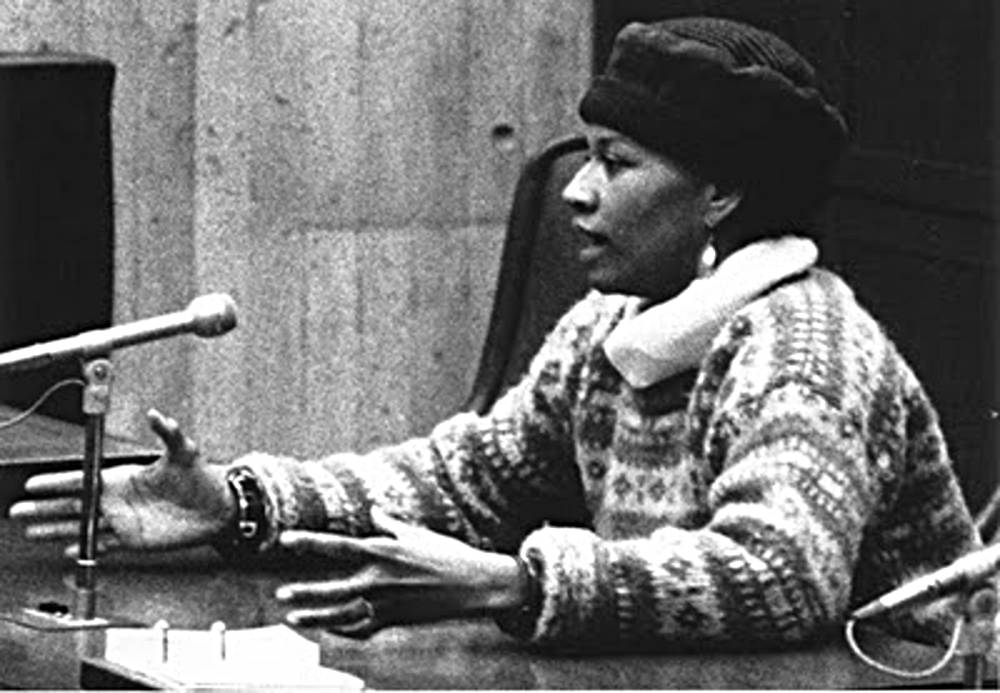

—Savina Martin

Many of those lost will be buried in “potter’s fields” — mass, unmarked graves for those who cannot be identified, claimed by family members or who are too poor to afford a proper burial. This annual event is always held on the Winter Solstice (also known as Homeless Persons Memorial Day), the longest night of the year, to bring attention to the brutal violence of poverty and homelessness facing millions of people.

This month’s briefing focuses on the housing crisis we face today and the homeless organizing that is building in response. It includes insights from seasoned leaders of the NUH who have launched a “Winter Offensive” against this tragic failure of our economic and political systems.

As Minister Savina Martin, a veteran of the NUH, says below: “We, the people, call out the richest country in the world: How dare it have its people and its beloved sleeping in doorways, in bus stations, under bridges and living in shelters for life, in the midst of abundance. It fails to feed, clothe and release the death, servitude and slavery of our working poor, who labor two and three jobs to feed their families and stand in long bread lines. And so let us demand on this day the right to bread, peace, land and security and claim the resurrection of the National Union of the Homeless, the National Welfare Rights Union, the Freedom Church of the Poor and the Poor People’s Campaign and many, many more partners. Enough is enough.”

The Crisis of Homelessness

Before the pandemic, there were 10 million people who were homeless or on the verge of being homeless. In the early weeks of the lockdown, homeless families began taking over abandoned homes and buildings so they could safely distance and meet some of the public health requirements of containing the virus. Cities across the country began housing homeless people in hotels and the CARES Act included protections against eviction and foreclosure. These measures were extended as a matter of public health by the CDC in September and most recently by the COVID-19 December stimulus package.

While necessary to contain the spread of the virus, these measures offer the barest protections given the scale of the crisis at hand. There are 30-40 million people at risk of eviction due to the pandemic and devolving economic conditions. The CARES Act, CDC order and December 2020 stimulus leave out millions of people and none of these measures canceled rent or housing payments that are due, meaning that households are still responsible to make those payments. According to the Eviction Lab, the typical tenant facing eviction in New York City is behind three months’ worth of rent. Some 12 million households are facing more than $5000 in back rent and utilities by January and, as the K-shaped recovery continues, the Federal Reserve of Philadelphia is reporting that more and more people are using their credit cards to pay for their housing.

The shelter system, which was unable to address pre-pandemic homeless conditions, cannot withstand a crisis of this magnitude. The NUH and other housing organizations, including the Western Regional Advocacy Project, National Low-Income Housing Coalition and Homes Guarantee have been at the forefront of raising this alarm for years. More recently, they have blocked eviction hearings, organized campaigns to cancel rent and are calling for our human right to housing to be realized.

Even J.P. Morgan Chase has called for an expansion of public, affordable and low-income housing, stimulus payments and expanded unemployment insurance for poor and low-income households. Less a sign of the bank’s goodwill towards the poor, their recommendations indicate that the polarization between wealth and poverty has hit a breaking point. As tens of millions of people go hungry and closer to the streets, billionaires have seen their wealth increase by $1 trillion. The crisis of homelessness reveals the hypocrisy of a political and economic system that tolerates these two extremes.

This is why homeless and unhoused people are fined and jailed for the most common human needs, like standing, resting and sleeping. Aaron Scott from Chaplains on the Harbor, a ministry that is deeply rooted in the poor and dispossessed communities of rural Washington state, describes the criminalization of homeless people as political repression: “We have a much bigger problem than individually heartless politicians and assailants…Unhoused people are not targeted by the system because they are weak and helpless. Unhoused people are targeted because their struggles reveal the fundamental lie of this economy. They are targeted because when they speak up, the foundations shake. They are targeted because their lives and stories have the power to break this system.”

Unhoused people are targeted because their struggles reveal the fundamental lie of this economy. They are targeted because when they speak up, the foundations shake.

The National Union of the Homeless, Then and Now

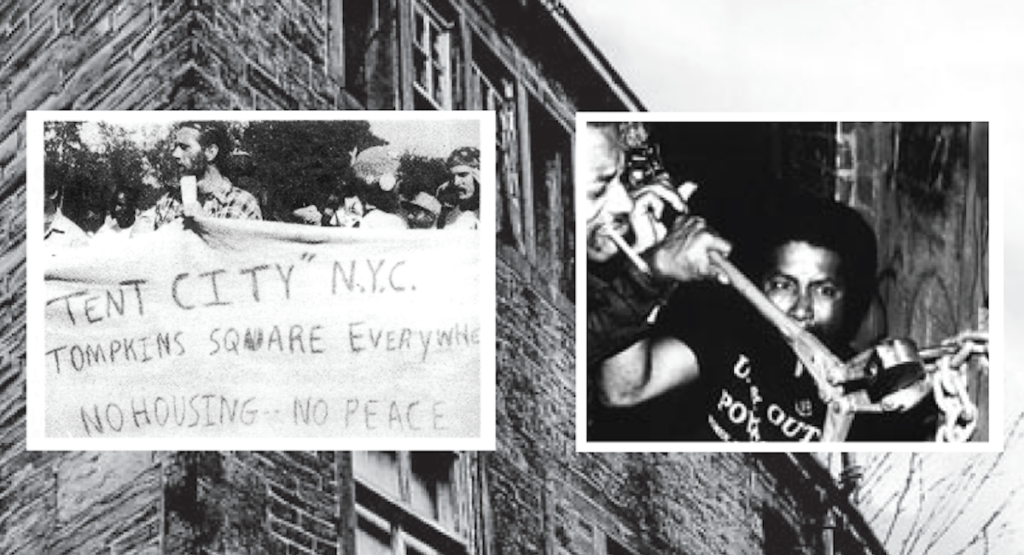

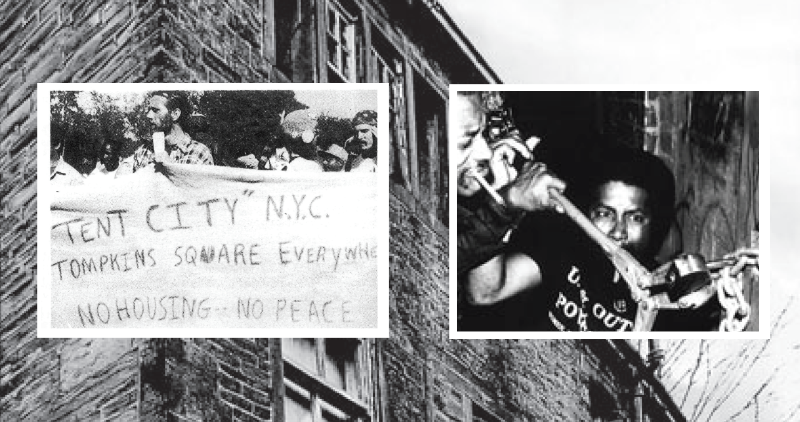

In the documentary film, Takeover, Ron “Cas” Casanova uses a bolt cutter to break through the locks of an empty public housing unit. Cas was homeless for most of his life. He was also an artist and Vice President of the NUH. He helped organize the first nationally coordinated effort to occupy federal housing units in 1990. Across 8 cities, members and leaders of the NUH planned these takeovers to house homeless families, but also to reveal the unnecessary violence of homelessness. The homes they seized were vacant public housing units, many of them with heat running through them, while the families they moved in were living unsheltered and facing a bitter winter. As Cas says in the film, “I’m dying in the streets. I think that should be against the law.”

The NUH was formed in the late 1980s, when the phenomenon of homeless families seemingly burst on the scene out of nowhere. Anthony Prince, General Counsel for the California Homeless Union, spoke to this rise of homelessness at the Kairos Center’s Moral Policy Conference: “Of course, homelessness didn’t just appear out of nowhere. It was simmering and developing as the result of this massive deindustrialization crisis that hit the whole country during the late 70s and early 80s, and finally manifested in the form of people losing their homes, losing their possessions and being pushed into the streets. By the 1980s, homelessness was no longer a skid row or transient affair. It became structural, with a growing number of homeless children and entire families.”

At its peak, the NUH had 35,000 members in 25 cities. For the first time in the history of the country, a union of homeless people, led by homeless people, organized by homeless people, was reaching a certain critical mass. Willie Baptist, a formerly homeless and long-time leader, educator and organizer of the NUH, describes some of the significant victories they were able to achieve in his book, Pedagogy of the Poor: “We forced city councils in D.C. and Philadelphia to give homeless people the right to vote. No matter if you had a house or not, if you could identify a corner or a shelter, you could vote. In a number of cities we won the right to shelter. We did all kinds of stuff that built up our sense of ourselves, our self-worth. The head of the Union, Chris Sprowal, was named in USA Today in 1987 as one of the top 10 leaders to watch for in that year.”

This is also what made its demise so painful. The crack cocaine and drug epidemic ravaged the Union and came to be seen as chemical warfare, as chapter after chapter broke down. Its leadership was also unable to prevent their victories from being turned against them. According to Baptist, “[In Philadelphia], we were able to establish the Dignity Housing Programs — a multimillion-dollar homeless program run by homeless people….[because we were networked across the country], local chapters copied that program in Oakland, Minneapolis, and other cities. But certain people who were assigned to run the programs became more closely tied to the housing department than to the Union of the Homeless. Then the housing department began to make demands on our structure that weakened the relationship of the Union of the Homeless to those programs.”

In 2019, the NUH was reconstituted to address the current housing crisis. Drawing on the lessons of the past, they are devoted to the proposition that every single person has the right to live. Their mission is to “work tirelessly for the human right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, for social and economic justice for all. We dedicate ourselves to raising the awareness of our sisters and brothers, to planning a sustained struggle and to building an organization that can obtain freedom through revolutionary perseverance. We pledge to deepen our personal commitment to end all forms of exploitation, racism, sexism, and abuse.”

Now with local chapters in nearly a dozen states, the NUH is organizing thousands of people and preparing for more. Their leaders have offered lifelines to survivors of the California fires who lost their homes overnight, while others have built and rebuilt encampments that have been razed and swept by local police. “There isn’t a city — small, large or midsize — where you don’t see tents and shacks and lean-tos and tarps and people sleeping in cardboard boxes in this country,” said Prince. “Millions of people in this country do not have stable housing and many of them get pushed into this status of having no housing whatsoever. But we stand in a historical moment, where we can be part of this movement to change this country and we’re not just about making things a little bit better. We are about ending homelessness.”

I’m dying in the streets. I think that should be against the law.

Fight Poverty, Not the Poor

One of the most important battles waged by the NUH across these decades and into the present is to confront narratives that blame the poor for becoming homeless. Their slogan of being “one paycheck away from homelessness” draws attention to the precarious conditions that precipitate homelessness: a lost shift at work, a health crisis, car accident or any other sudden change in our fragile daily lives can push millions of people over the edge. The Poor People’s Campaign’s reference to the 140 million who are poor or “one emergency away from being poor” echoes the profound economic insecurity that shapes the lives of over 40 percent of the nation.

When these structural and systemic causes are minimized, the policy solutions are at best inadequate or limited to making the shelter and welfare systems a little more humane. At their worst, these narratives contribute to further crisis and dispossession. One of the most devastating narratives from the 2008 sub-prime mortgage and financial crisis was to blame the borrowers who lost their homes, even though banks and financial institutions were knowingly making loans to people without adequate incomes, assets or ability to hold onto those homes (and disproportionately to people of color). These institutions were also repackaging and investing in those debts and then driving up interest rates, far beyond borrowers’ ability to pay. As a greater and greater proportion of household income went into paying mortgage debt, the crash was inevitable. It was not, however, the borrowers who were at fault, rather it was the lenders and investors who were aware of these risks and continued to push the economy into crisis.

The policy response to the crisis notoriously prioritized Wall Street and bailed out the banks instead of homeowners. This precipitated a wave of foreclosures that continued for at least a decade and wiped out the wealth of Black and Latino communities in particular. Meanwhile, many of the jobs that returned as the economy “recovered” were low-wage, precarious jobs: the post-recession economy had 2 million fewer mid- and high-wage industry jobs, but nearly as many more low-wage jobs, leaving the post-recession economy even more fragile. In fact, many of these new low-wage jobs were in food services, retail and administrative and support services, all of which have been at the forefront of the pandemic lockdown and the post-pandemic recession of 2020. In some ways, the homeless crisis we are witnessing today is the result of those economic policies that have prioritized the wealthy instead of the poor.

A lost shift at work, a health crisis, car accident or any other sudden change in our fragile daily lives can push millions of people over the edge.

Enough is Enough

At the Kairos Center’s Moral Policy Conference in October, Minister Savina Martin offered her testimony as a veteran of the NUH and a veteran of the military. Savina has witnessed and organized amidst multiple forms of violence exacted on the poor. Below, she makes a powerful call for Jubilee in its truest sense: freedom from homelessless, hunger, debt and poverty.

Indeed, with one in four Americans jobless or earning poverty wages, we need more than to secure housing. We need to secure the ability and resources to stay housed. This means large-scale federal policy interventions that expand housing and social welfare programs, rent cancellation, immediate debt relief, as well as implementing living wages, income guarantees and more. The Poor People’s Campaign has listed these policies among its 14 Policy Priorities for the first 50-100 days of the Biden-Harris Administration and the Congressional Progressive Caucus has included them in its 7-point “People’s Agenda” for 2021.

As we enter the new year, we, the people, are rising up and moving forward together, to make sure all of our needs are met. Enough is enough.

For more information on the National Union of the Homeless, visit them online or email directly at 2020nuh@gmail.com.

“My name is Savina Martin. My pronouns are she, her, hers. I’m from Boston and grew up in Roxbury.

For me, the National Union of the Homeless became a safe sanctuary for me and countless others. We had a place to study and have strategic dialogues where we could think together and learn together. My comrade, the late Ron Casanova taught us about the “struggle being a school” and that each of us had the responsibility to teach others — “Each One, Teach One” was the title of the book he wrote. The National Union of the Homeless today draws on the good and painful lessons of that past experience during the 1980s, when we first began organizing throughout the country.

We’ve heard so much from everybody. Let’s just take this ruach, this breath, this time to breathe it all in, in this time of war being waged against the poor. So I’m going to put on my ministerial hat and maybe we’ll go to church for a second. So listen, just listen.

I want to bring you a moral message from the valley and the trenches of pain that we have been in. We have been face-to-face with our Goliath, the system that created this moral crisis. Before this pandemic, all hands have already been on deck. We were tossing our smooth stones at the giant’s Achilles heel, at the state houses, praying on Supreme Court steps, crying in the streets, getting arrested and raging at the machine. Yes! We are in a moral crisis. And today we are the moral witnesses of our time.

The book of Isaiah states, “Woe to those who legislate unjust laws and violent policies against us, that leave us widowed and orphaned.” Today, we’re talking about redefining our national security, to include other issues like economic security, energy security, and environmental security. And we know the poor have been under attack right here on our own soil.

As a young veteran, I experienced great trauma, being poor and homeless and eventually finding my way to the National Union of the Homeless, like many other brave and courageous souls did at that time. We rang the alarm all around the country, witnessing the most violent and visible expressions of poverty, which the system named homelessness. We rang the alarm that our houseless were burning to death, trying to keep warm during the cold and brutal winters and that our addicted were caught up in the vicious throes of chemical warfare, overdosing at the city gates without any treatment on demand.

If they called to get treatment, they were asked, ‘do you have insurance?’

‘No.’

‘Then call us back every day for two weeks until a bed opens.’

No, we are not safe.

I’ve witnessed this up close and personal in Boston’s ‘Methadone Mile,’ a place where the dry bones in the valley live and die, a place that now has stretched from one mile to three.

Today, we bear moral witness to the fact that this nation neglects the poor and vulnerable and takes advantage of low-income and poor students and families through the military industrial complex, the prison industrial complex and the shelter industrial complex. It fails to feed, clothe, and release the death, servitude and slavery of our working poor, who labor two and three jobs to feed their families and stand in long bread lines. We have witnessed struggling veterans who are forced to return home to live in war zones they left, after returning from deployment and combat with deep psychological trauma, serious wounds and addictions. We have seen luxury condos push out our communities time and time again and promises for better schools, better housing, better health all broken.

We, the people, call out the richest country in the world — how dare it have its people and its beloved sleeping in doorways, in bus stations, under bridges and living in shelters for life, in the midst of abundance.

Throughout the Bible, different scriptures indicate that the ram’s horn is to be blown in necessary times: with the blowing of the ram’s horn or shofar, let it be known that the season of Jubilee is at hand and we are proclaiming this even in the face of this moral crisis and the urgent struggles of our time. We proclaim this a time of release, relief, reconstruction and restoration! While the scripture speaks of the year of rest, we know that it means that the rest of us, the poor and dispossessed of this nation, shall take up this platform and provide for the common defense, that we shall reprioritize the resources to meet the needs of the rest of us, who raise our fists at the system that has turned its back providing for the needs of the sick and who beg at the gates of the city.

In this time of Jubilee, the houseless shall walk into the halls of power and demand housing now. We, the people, demand on this day, the right to bread, peace, and land and security, and claim the resurrection of the National Union of the Homeless, the National Welfare Rights Union and the Freedom Church of the Poor and the Poor People’s Campaign and many, many more partners. Enough is enough.

During the high holy season, we proclaim that we will continue to unite the poor and dispossessed people of this land. We will build the power of the 140 million so this country meets our needs.

We only organize to get back what’s ours.”