We enter 2021 with a new Administration, a Democratically controlled Congress and the opportunity to take up the challenges we are currently facing with renewed urgency and rigor. As a reminder of where things stand: the pandemic claimed 80,000 deaths in January, deep rifts in our national politics manifested in violence (and threats of more violence) on January 6th and the fiscal health of our economy is disintegrating at the local level. State and city governments are facing severe budget shortfalls, estimated at $480 billion — $620 billion through 2022. According to the Economic Policy Institute, “these subnational governments spend about $4 trillion every year in the economy, making them the second-largest source of spending outside of the federal government. If they are forced into crash-cutting, the entire economy will suffer.”

This is, however, exactly what has happened — in the second quarter of 2020, state and local spending experienced its biggest drop in nearly 70 years, falling 6% on an annual basis. By the end of 2020, state and local governments had laid off 1.3 million workers and cut public education funding for k-12 by several billion. Without a massive infusion of federal resources, more progressive taxation and critical investments in jobs, expanded social welfare programs, public health infrastructure and more, these cuts will continue and escalate.

While President Biden has indicated a willingness to engage in deficit spending, there is also a risk that calls for unity will temper how far our federal government will go in its relief efforts. The debate unfolding right now is whether the proposed $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan is too much to spend. What should be prioritized and what can be cut? How much do we give up to compromise to achieve bi-partisan consensus? Can we even reach that consensus and how far do we go without it?

We know that if the calls to compromise trump what must be done to heal and build back better, then one of the biggest cuts will be to the aid that is desperately needed for state and local governments. This will accelerate the austerity measures that are already ongoing and push the 140 million (and more) people who are poor or just one emergency away from poor into even more hopeless conditions.

We have seen this before. After the Great Recession, federal aid was pumped into state governments through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. When this ended prematurely, governors turned to austerity measures to balance their budget. This stalled the recovery and resulted in catastrophic decision-making at the local level. In 2010, for example, cities from New York City to Sacramento began cutting their fire department budgets. Through “rolling brownouts,” firehouses were closed on different days, increasing response times and compromising fire and emergency services. In Philadelphia, the Taing family lost two of their children, Peterson and Kevin, in a house fire. The boys were 7 and 9 years old and their home was within walking distance of a browned out firehouse that was closed for the day. Mayor Nutter had been trying to cut $3 million when the policy was implemented.

In this month’s policy briefing, we take a look at the example of Detroit. Once the “City of Industry,” it has experienced decades of deindustrialization, a declining tax base and austerity politics that prioritized the rich over the rest. It offers a stark study in why we must push back against austerity now and reorient our economy from the bottom up.

Detroit offers a stark study in why we must push back against austerity now and reorient our economy from the bottom up.

A Brief History of Detroit’s Rise and Decline

In the early 20th century, Detroit was the auto manufacturing capitol of Michigan, the U.S. and even the world. Thousands of workers moved to the northern state during the Great Migration to take advantage of the wages that Henry Ford was offering at the time, especially to Black workers. By the early 1930s, Ford’s iconic River Rouge plant held over 85,000 workers. To maintain order and loyalty, Ford implemented a wage structure that kept Black and white workers apart in the plant, until unions began breaking through those barriers and desegregating the workforce several years later.

These steady jobs and the expansion in manufacturing during WWII meant that the city’s population was growing, peaking at nearly 2 million in the 1950s. Many residents, including Detroit’s Black population, were able to afford to purchase and own their own homes.

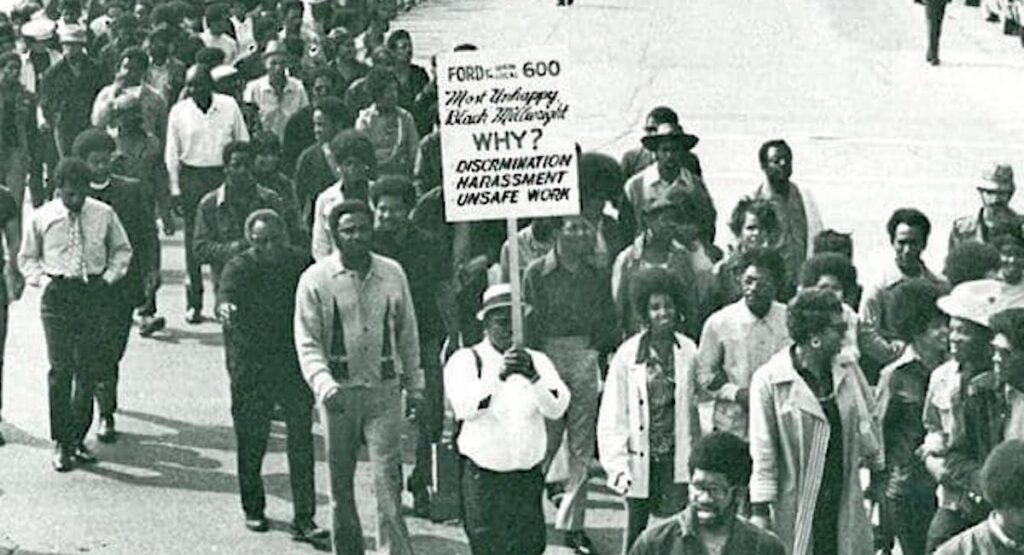

By the late 1960s, however, Ford and other plants began automating more of their manufacturing operations. From the late 1970s to the early 1980s, the “City of Industry” started seeing a rapid deindustrialization: the River Rouge plant went from having tens of thousands of workers to only 30,000 in 1960 to 9,000 in 1990 and about 6,000 today. Chrysler, whose manufacturing was concentrated in the City of Detroit, closed virtually all of its plants in the city between 1979 and 1982 as part of its restructuring plan, but kept its suburban plants open. This alone eliminated 35,000 auto jobs in the City of Detroit in these years. This was in part to destroy the militant center of the UAW, where Black workers had organized the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in these Detroit factories. More generally, the restructuring helped precipitate a massive decline in Detroit’s population, from 1.9 million to less than 700,000.

With this, the tax base of the city was eroded, requiring the city to take out municipal bonds and become indebted to financial institutions, declare bankruptcy, dismantle its public assets and infrastructure, break its pension agreements and even close half of its public schools.

Foreclosure Crisis: 2005 to 2016

Despite the job losses and population decline, Detroit neighborhoods maintained a steady base of homeowners through the 1990s and early 2000s. Many of them were elderly and on fixed incomes, but they were still able to hold onto their homes. In 2005, Detroit had one of the highest Black home ownership rates in the country.

Also in 2005, the subprime mortgage crisis started to unfold across the country. Banks were refinancing home mortgages and through that process locking people into “adjustable rate mortgages.” They were also overvaluing homes to raise the amount of the mortgages that were being issued — mortgages would start off at low interest rates, but then abruptly increase to higher rates, on higher-valued homes. At some point, homeowners, especially those on fixed incomes, could no longer pay their debts. As this spread from city to city and state to state, the mortgage default crisis eventually evolved into the 2008 financial crisis.

In part due to its high rate of Black home ownership, Detroit had one of the highest rates of subprime lending in the country. The city saw some 65,000 mortgage foreclosures between 2005 and 2010. Nationally, because so much Black wealth was tied to home ownership, more than half of Black wealth was wiped out in just a few years. (According to new research from mortgage giant Freddie Mac, homes in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods were undervalued as compared to their contract price, which ends up impacting household wealth.)

Many of the banks involved in the sub-prime crisis were bailed out by the federal government and paid back full value for their losses from the mortgage defaults. When Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac took over those mortgages, they began selling the homes on auction blocks, more often to investors than the owner-occupants.

In Detroit, homeowners were kicked out and replaced with new homeowners who became responsible for building back the tax base of the city. Because of the over-inflated appraisals that were part of the predatory lending schemes, these new homeowners were taxed at higher rates than the value of their homes. Some homeowners who paid less than $5000 for their homes were being taxed $26,000. Studies estimate that between 2010-2016, over 90% of Detroit homeowners were overtaxed by at least $600 million. About 28,000 of those who were overtaxed were foreclosed on and lost their homes. Another 59,000 homeowners still owe $153 million in back taxes, but were also overtaxed at least $221 million from 2010-2016. They have more than paid what is owed, but still face foreclosure.

This “predatory” form of austerity politics has unfolded across the country as cities and counties struggle to meet budget shortfalls. Ferguson’s poor, Black residents were subjected to excessive fines and fees, as they were in Washington, D.C. and New Orleans, to boost city revenue. Rural counties have started filling jail beds to do the same. Aaron Scott from Chaplains on the Harbor has seen this firsthand in Grays Harbor County, Washington (which is predominantly white) and how it leads to further disinvestment in poor communities. “Why invest in children, or healing and recovery, when there’s money to be made in keeping the jails full?,” he asks.

Why invest in children, or healing and recovery, when there’s money to be made in keeping the jails full?

Emergency Financial Management

After losing one-quarter of its population from 2000 to 2010, Detroit’s tax base was ruined. The city eventually became trapped into “swaps,” where they were obligated to pay a fixed interest rate on certain debt obligations while the banks they were in partnership with paid adjustable interest rates. The 2008 bailout effectively brought interest rates down to 0, leaving Detroit paying the banks 5% interest rates, when the interest owed was only 0.5%. This precipitated the city’s bankruptcy crisis, where it was forced to bring in an Emergency Financial Manager (EM) to balance its books.

Emergency management was both a form of voter suppression and austerity. Through appointment by the governor, Michigan’s emergency manager law gave these individuals sweeping powers without any accountability. The EM had the power to break contracts and pension agreements and even close down half of the city’s schools to pay back Detroit’s debts to Wall Street. One of the measures initiated during the bankruptcy was mass water shutoffs: over 100,000 people lost their access to water so that the bondholders of the city’s water debt were paid their due. At the same time the city was going after residents to pay their inflated water bills, Nestle was able to pump millions of gallons of water from the Great Lakes for $200 a year.

Emergency management was implemented in other cities in Michigan, mainly majority Black cities. In each case, the city’s budget was balanced on the backs and lives of its residents. This happened most notoriously in Flint. There, an emergency manager switched the city’s water source over to the Flint River in 2014, poisoning the city’s population of 99,000 people to pay bondholders and financial interests.

Emergency management was implemented in other cities in Michigan, mainly majority Black cities. In each case, the city’s budget was balanced on the backs and lives of its residents.

We All Stand to Lose

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, nearly all 50 states and Washington, D.C. are either proposing or have already taken measures to address their pandemic related budget shortfalls. This includes layoffs, furloughs and hiring freezes; cuts to Medicaid, adult dental programs and other state health programs; cuts to public education (pre-K, K-12, college and universities), early childhood programs, as well as housing programs, parks and recreation, social services, energy programs, corrections, tourism, public broadcasting, highway repair and more; renegotiating retirement and pension programs; and, in some states, across the board cuts to every public agency.

Many of these cuts are coming on top of the austerity measures that were taken during the Great Recession. In other words, they are scaling back already scaled back budgets. While some are raising taxes on alcohol, gambling and even high income earners, these efforts will not be enough to address the long-term erosion of their tax base from the bottom up.

As in Detroit, this did not begin with the pandemic. The recovery from the Great Recession was a low-wage recovery and for more than a decade, women and people of color were disproportionately shifted into low-wage, temporary and precarious jobs. Savings were spent down and household debt was on the rise heading into 2020. Before the pandemic, there were already 140 million people who were poor or one emergency away from being poor. It was the pandemic that brought them closer to that emergency.

In fact, a recent study from Harvard shows that low-income households (defined in the study as households with incomes less than $60,000) are more financially fragile than they were before the pandemic: their spending exceeds their income, they are unable to pay their bills and have worked through their savings. It also found a widening gap between these households and higher income households. When the expanded unemployment payments expired, these low-income households, women and unemployed workers experienced an even greater decline in their economic conditions. These households are facing higher debt burdens, with no ability to pay.

All of this fundamentally weakens our economy, in part because cities and states cannot build back their tax base from these households. As the authors of the Harvard study concluded, “While some may benefit from these fractures in American society, clearly, we all stand to lose.” This is a lesson we must learn from Detroit, which lost its tax base through deindustrialization, population decline and predatory lending, and then tried to build it back up through austerity and emergency management that preyed on the poor. This is what brought them to bankruptcy and further decline.

These predatory, austerity politics are found in conservative and liberal states. In Kentucky, the wealthiest 1% pay only 7% of their income in state and local taxes while the poorest 20% pay nearly 10% of their income. In New York, state spending on social services and social welfare agencies has gone down by 32% since Governor Andrew Cuomo was elected into office. At the Kairos Center’s “Moral Policy in a Time of Crisis” conference, Rev. E. West McNeill elaborated on these austerity politics, saying, “When COVID hit, it provided the excuse for the state to double down on this kind of austerity, so schools were flat funded this year in the budget that passed in April [2020]. Even before COVID hit, Gov. Cuomo was pushing a plan to cut Medicaid. He wanted to cut it by up to $2.5 billion. New York State has had a model program to fund home care services through Medicaid, which is especially used by folks with disabilities, and he significantly cut that this year. He also cut funding to public hospitals at a time when public hospitals in New York City were being overwhelmed with COVID patients. From March to June, billionaires in New York State got $77 billion richer, but our state revenue is down $13 billion.”

From March to June, billionaires in New York State got $77 billion richer, but our state revenue is down $13 billion.

When You Lift from the Bottom, Everybody Rises

In July 2020, 156 economists published an open letter calling for recurring direct payments to boost economic activity. The letter was written as states were re-opening without adequate precautions. It cautioned that without bold economic policy, the economic impacts of expiring unemployment, dwindling savings and ongoing job loss would be devastating, especially for low-income households, women and Black and brown workers.

A few months later, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Jerome Powell said, “We’re not going back to the same economy, we’re going back to a different economy.” He reiterated that low-wage workers would need stronger government support as the economy that emerges from the pandemic will depend more on automation and remote work that would leave many low-wage workers left out of the recovery.

Heeding these warnings, President Biden said on January 22, “The bottom line is this: We’re in a national emergency, and we need to act like we’re in a national emergency. So we’ve got to move with everything we’ve got…So let’s use the tools, all of them.” In the first days of his Presidency, he has issued a series of executive orders on ensuring an equitable pandemic response, vaccination, worker safety and expanding our public health systems; immigration; the Keystone XL pipeline and other environmental concerns; modernizing regulatory review; prison reform, and more. The American Rescue Plan he is asking Congress to implement calls for additional stimulus payments, raising the minimum wage, expanded paid family and medical leave and unemployment insurance, aid to local and state governments and small businesses, resources for schools to re-open and operate safely, extending the eviction and foreclosure moratoriums, expanding our food security and welfare programs, childcare, resources for Indian country and more.

While this is a welcome start, it is not enough. We need income security; real housing security and not an expansion of our shelter system; relief from student loans, rent, household debt, mortgage debt, medical debt, utilities’ debt and municipal debt; and immigrants, regardless of their status, must be eligible for all of these programs. We also need the federal government to set an example on progressive taxation and redirect our abundant resources towards meeting the needs of the poor, most vulnerable and at risk.

This does not mean relying on philanthropy, charity or our existing systems of taxation and appropriations to catch the dregs from our inherently unequal economy. In California, nearly 40,000 people have died from COVID-19 and between 4-5 million people, or approximately one-third of California households, were at risk of eviction in 2020. Meanwhile, billionaire wealth soared during the pandemic, and at one point was $90 billion greater than the anticipated state budget shortfall. Buoyed by the massive stock gains and income growth among its wealthiest residents, California has headed off its budget crisis from its widening inequality. This is not the example to follow.

Rather, we must flip the logic of our current economy on its head. Instead of austerity, we need a program of abundance for the poor.