The second day of the Kairos Center’s conference on “Moral Policy in a Time of Crisis” opened with a discussion of systemic racism, taking a long view of the policies, systems and structures that have perpetuated this injustice. This article features comments from Wendsler Nosie Sr., Chairman and Councilman of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, Dr. Jeanne Theoharis, distinguished professor at Brooklyn College, and Leo Vilchas, Co-Director of the Union de Vecinos in Los Angeles, California.

When taken together, these three speakers explore America’s racism from the origins of the country to today. Mr. Noise begins, as all discussions of American racism should, with the history and legacy of the persecution of indigenous peoples. He proposes that America needs an honest history to understand the origins of the injustices we continue to experience and witness today.

Dr. Theoharis expands on this honest history by bringing to light the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was focused as much on the insidious white liberalism of the North as more violent in some ways than white conservatism in the South. Mr. Vilchas carries this through to the challenges facing organizers today, making clear how urban “development” is paving the way for gentrification and the displacement of poor communities of color. His comments make it clear that racism is just as dangerous today as it was fifty years ago.

Given the emboldened activity of white nationalist and supremacist groups, including most recently the mob riots in Washington D.C. on January 6, 2021, it is easy to pay attention only to the most violent expressions of systemic racism. But these other facets of systemic racism continue to shape our society, including what we expect and demand of our government and our economy. Indeed, ending systemic racism is not just a question of achieving racial justice, but at the core of our national security and general welfare.

Watch the full panel discussion here:

[aesop_video src=”youtube” id=”MCtrSCe6ncA” align=”center” disable_for_mobile=”on” loop=”on” controls=”on” mute=”off” autoplay=”off” viewstart=”off” viewend=”off” show_subtitles=”off” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Wendsler Nosie:

I’m enrolled in the Apache San Carlos reservation in southeastern Arizona. San Carlos is really a unique reservation because we hold 15 different types of Apaches and within the 15 types of Apache we have our clans.

My grandfather, my great grandfathers and grandmothers were all brought to San Carlos as prisoners of war and I am descended from the Chiricahua. Other people were mistakenly brought here as well, but not in great numbers. The Chiricahua Apaches were taken to different places, the majority of us were exiled and went to Florida and eventually Alabama and ended up in Oklahoma. So there are only a handful of Chiracahuas who remained and I come from one of those families. My mother is a Yavapai Apache. At the time when the United States military came into what is now Arizona, the Yavapai people, in their attempt to remove them, killed two individuals who came from prominent families back east. The military really came after the Yavapais and brought them to San Carlos as prisoners of war, too.

This is where American history starts. The star of Arizona on the American flag represents the conquering of our people and the taking of our resources. The reservations we were taken to were prisons. Imagine going to a prison, and then them telling you, “Okay now, this is where you have to live.”

We have seen the French and how they colonized people above us, in Canada. We have seen how the Russians migrated from Alaska down into the West Coast of Canada and into what is California today. We have seen the Spaniards who came up from below us. Then we saw the white people from England and their partners who came right across into this country. We have seen this mass migration taking place and in our first encounters with these people, the thing they were looking for was gold to accommodate their countries, with their ways. It was all about what they could take.

How do you overcome something like that and what was done by a military in a war against our people? In order for the Apaches to heal, we had to go back to that first chapter and its ugliness. We have now healed from the past, so that we can move forward from an honest understanding of what happened.

It’s the same thing for the rest of America — if we don’t go to the very beginning and see that ugliness, then we’re standing on a foundation that is not real or true. We have to go back to that beginning to understand what is happening today, with the owners of the country versus the poor of the country. It is all about ownership and that is what we experienced from the taking and taking and taking from our people.

[aesop_quote type=”block” background=”#31526f” text=”#ffffff” align=”left” size=”1″ quote=”It’s the same thing for the rest of America — if we don’t go to the very beginning and see that ugliness, then we’re standing on a foundation that is not real or true.” parallax=”off” direction=”left” revealfx=”off”]

We also know that, today, this is not just about us. It’s about everybody. Our prophecy talks about the rattlesnake: when it shakes, it is a warning. What we know in our holy places here, the holy places are rumbling at what is happening in the world and in the country. But the prophecy goes on to say that one day it is not going to rumble anymore. When that day comes, that means we will have destroyed everything. What frightens us as native people is we’re seeing the rattlesnake begin to grow without rattles. A lot of that is from the environmental impacts that are going on in the country, including on our lands.

The work I’m doing to save Oak Flats is exposing everything that has happened to the people in Arizona when it comes to mining and how the whole southwest will be affected if we lose our water source or if it is poisoned. Oak Flats are the mountains. When the weather comes in from the Gulf of Mexico, the mountains are so high they’re like knives: they carve the clouds and the clouds move in different directions and this is what gives them their moisture and then they move that water to where it is supposed to be. It’s a whole system working together. If these mountains are destroyed, the moisture will never reach where it should be going. We’re changing the environment. It is happening right in front of us.

And as long as we’re left out, we will never be able to heal and fix this place. As long as we’re on our own, we can’t do what is necessary. You know, the Indian people here were given knowledge of the mother, the earth. And the white people were given the knowledge of fire. And the Asian people were given the power of wind. And then the Black people were given the power of water. And so for me, when we come all together in this sense, we can relate to each other, learn from each other and our histories and what they mean for us now. We pray that that day will come.

Dr. Jeanne Theoharis:

Thank you for having me. It’s great to be here. I want to pick up Wendsler’s point about the need to be honest and what an honest history is. I teach a class on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements at Brooklyn College and sometimes I start with a trick question, which is: “what was the largest civil rights demonstration in the 1960s?” Obviously, because I’m asking the question, students get a little nervous. They want to say the March on Washington, because that’s what we know. That’s the big one; there’s a quarter of a million people in DC, but that’s not the answer.

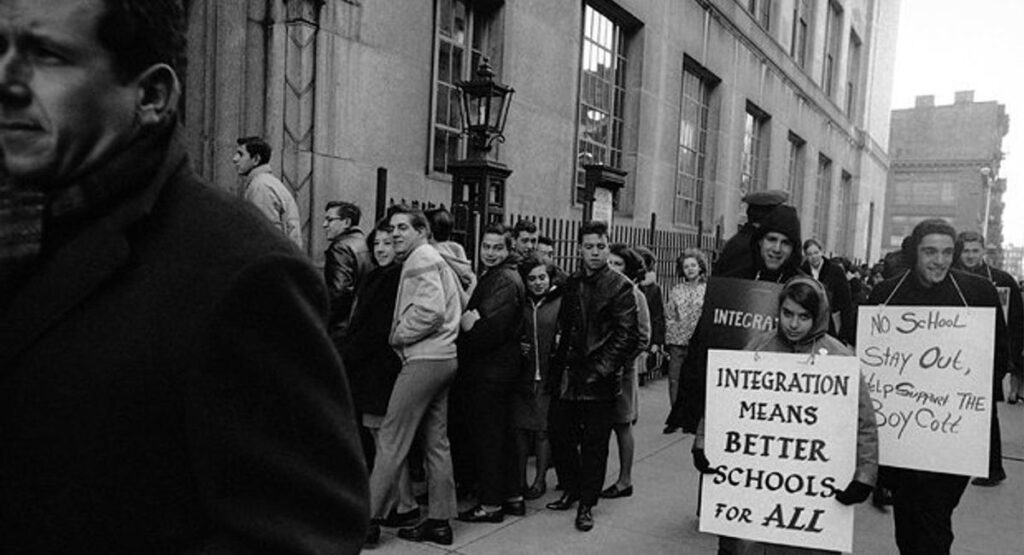

The answer is actually the next year. In February of 1964, almost a half a million students and teachers stay out of New York City public schools to protest the fact that it has been ten years since the Brown decision and New York City still doesn’t have a plan for desegregation. The schools in New York are segregated and growing more segregated. In this period of American history, we’re seeing increased migration both from Puerto Ricans (from the island) and African Americans from the South into places like New York. So, schools are getting more overcrowded, they’re getting more underfunded, they’re getting more under-resourced, they’re getting more segregated. In fact, in parts of New York City they’ve gone to double session days in Black and Latinx schools, because they don’t want to rezone so that Black students and white students would go together.

This was the biggest civil rights demonstration of the 1960s and yet, I think many of us have never heard of it, even though the Civil Rights Movement is one of the few things that makes it into our textbooks and it’s one of the few moments where we talk about race in U.S. history.

But, the ways we see the Civil Rights Movement — and what we don’t see about it — greatly impacts how we think about the nature of structural racism in this country. Part of the way that we’ve come to see the Civil Rights Movement is around the Klan or it’s the white Citizens Council and people spitting and burning crosses. And that is absolutely one facet of what racism looks like, but it’s only one facet. A lot of the resistance to school desegregation, to housing desegregation, to changing how law enforcement worked came in a much more — and I’m going to use Dr. King’s words — “polite” manner.

Three months after the Watts uprising, Dr. King takes to the pages of the Saturday Review, which was one of the big magazines of the time, and he writes: “In my travels in the North, I have become increasingly disillusioned with the power structures there. [Those] who welcomed me to their cities, and showered praise on the heroism of Southern Negroes. Yet when the issues were joined concerning local conditions, only the language was polite; the rejection was firm and unequivocal.”

This is a King that we’re not so familiar with. King is saying this in 1965, because in the years before the Watts uprising, he had crisscrossed the country partly to raise money for the southern movement, but also to join with and stand with northern struggles: challenging school desegregation, challenging housing segregation and challenging police brutality. In fact, King goes on to write, “As the nation’s Negro and white trembled with outrage at police brutality in the South police misconduct in the North was rationalized, tolerated, and usually denied.” He is giving us a way to see what the Civil Rights Movement was taking on that looks more like the racism we fight today.

In cities like New York City, LA, Seattle, Detroit, we don’t see people opposing the Civil Rights Movement on the grounds of “segregation forever” like George Wallace is doing in Alabama. What they’re saying is something a little bit different. First, we see liberals saying: “We don’t have a problem here. We don’t have segregation: we have separation. “Secondly, they say: “We’re colorblind. We don’t see color here.” And “we don’t even keep records, so we don’t know. We don’t even know who goes to school where. We don’t keep those records.” Third, and I think most dangerously, northern liberals attempt to find ways to justify and explain the inequalities in their cities in the face of a growing Civil Rights Movement. They claim that certain communities don’t value education. In the same way, certain communities are plagued by crime, certain communities don’t have the right values for success.

These culture-of-poverty arguments are being made to justify deep inequalities in education, in the job market, and in policing. Over and over, we see Dr. King trying to call them out and being ignored. The northern activists he’s standing with in the early 60s are being called troublemakers and unreasonable. In fact, going back to that 1964 school boycott in New York, The New York Times editorialized against that boycott, calling it “unreasonable, reckless and violent.” So many of the terms we see used today against our protests are language that we see liberals using against movements in their own cities, even if at the same time they are supporting a Civil Rights Movement in the South.

The Civil Rights Movement is now one of the most lauded periods of American history. Surveys show that if you ask young people who the most famous Americans are (excluding presidents) the people they pick are King and Rosa Parks. And yet, the history we are given misses much of the opposition to those movements. Part of being honest about what our history looks like and what the Civil Rights Movement looks like is understanding what that opposition looked like.

So, what did white parents organizing against school desegregation call themselves in in New York in the 1960s? They called themselves “parents and taxpayers.” They’re not calling themselves pro-segregation. Instead they say, “We’re not racist, we’re just against busing.” And busing is going to be one of the lenses with which Northerners find a more palatable way to oppose school desegregation.

This history actually shapes the Democratic Party we have today. Senator Joe Biden got his start in the 1970s by protecting the interests of white parents by helping to pass multiple anti-busing laws.

One of the ways that parents thwart movements around desegregation in cities like New York, Boston, or L.A. is by saying, “These neighborhoods are dangerous,” or “we don’t want these kids going to our schools,” or “what we need is more policing.” King takes all of this on when he says, “When we ask negros to abide by the law, let us also demand that the white man abide by the law. Day in and day out, he flagrantly violates building codes, his police, make a mockery of the law. His police make a mockery of the law and he violates laws on equal employment and education and the provisions for civic services.” Here, King is calling out a second tactic. This first tactic is anti-busing, which becomes the way to shut down substantive school desegregation even though kids are being bused in all of these districts beforehand and white parents don’t object. The second tactic is crime, which we can see in the expansion of school policing. And once again, the Democratic Party picks up this issue. Out of this comes Clinton-era legislation, including the 1994 Crime Bill and the 1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, in addition to the expansion of criminalization and the curbing of the rights of defendants.

The third tactic is to cast public assistance and social citizenship as freeloading and to racialize it. There’s a rising movement against public housing and welfare that culminates in the 1990s, with Clinton passing both the 1996 Welfare Reform Law and then two years later, the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act, which targets public housing. Both of these racialize public assistance and thereby strip the social safety net.

[aesop_quote type=”block” background=”#31526f” text=”#ffffff” align=”left” size=”1″ quote=”I think if we’re going to have an honest history of systemic racism, part of that is reckoning with the full measure of opposition to the Civil Rights Movement.” parallax=”off” direction=”left” revealfx=”off”]

I think if we’re going to have an honest history of systemic racism, part of that is reckoning with the full measure of opposition to the Civil Rights Movement and the full measure of tactics that people undertook to try to thwart the rising movement not just in the deep south, but in the Northeast, the Midwest and on the West Coast by using the tactics of policing, criminalization, anti-social assistance and the rights of taxpayers as the new language of race in this country.

Leo Vilchas:

The first reality we need to understand is that this country was built on stolen land with slave labor and the exploitation of migrants. If we understand that, we understand that racism — systemic racism — is embedded in the history of our country. And if it’s embedded in the history, it’s embedded in the systems and institutions and the ways we operate. If it’s embedded in those processes and those systems and institutions, it is also part of our language.

The first reality we need to understand is that this country was built on stolen land with slave labor and the exploitation of migrants.

Here in Los Angeles and in lots of parts of the United States, we’re hearing about “development,” which can mean many things to a lot of people. It is very important to understand that if we are to talk about development, and can talk about development that doesn’t include the people who are most affected, the people who have been excluded by history, we’re going to talk about a development that doesn’t address the historic demands and needs of the people.

We live in Boyle Heights and it’s a community that was built by racism. Los Angeles was a segregated community where only white people lived. Our community, Boyle Heights, was the place where everybody else moved: the Jews, the Japanese immigrants, Mexicans, African Americans. Over time, this community became one of the most diverse communities in the city of Los Angeles. Then through other changes in history like the Japanese internment camps, discrimination, and another form of segregation, this became a very Mexican community. So, this neighborhood was built through racism and became a Mexican community segregated from the rest of the city.

Now, through “development”, we’re being asked to reintegrate into the city. And that’s what we call gentrification. The city, investors and the politicians who are invested in the development of this city and growth are saying it’s time for us to integrate into the city. They have lots of different plans to grow the city, to build more housing, but they’re not asking the people who live in this community: “what is it that you need?”, “what is it that you are lacking?”, or even “what is it that we are doing to you that created these conditions?”

Instead, they come to us and tell us we need more art galleries. And when we say no to the galleries or we confront the development of housing that doesn’t serve the needs of the most poor, they accuse us of being rude or being disrespectful. We want housing not only for Mexicans or immigrants, but for the homeless and anyone who is excluded or being pushed out of their housing. This is the development, the housing development, that we want, but the development of the planners and politicians is not this. In California, we live under a mostly Democratic state government and we still have police abuse, we still have segregation of people, we still have our problems. Our politics, our work, our development, and our building of a community must go beyond what we have today. It has to go beyond what’s been built. It has to go beyond escaping or responding to this emergency. It has to be built on the dream of those people who are excluded, on the desires of those people whose land was stolen. And this only takes place if we commit ourselves to an honest and inclusive telling of history.