At the time of the Kairos Center’s “Moral Policy in a Time of Crisis” conference last fall, there were more than 223,000 COVID-related deaths in the U.S. The death toll is now 516,000 and counting. This is an historic emergency, but we cannot forget that before the first official case on January 20, 2020, the country was already in the throes of a quieter, but no less deadly, public health crisis. Before COVID-19, this country had the lowest life expectancy, highest chronic disease burden, highest suicide rates and highest rate of avoidable deaths among wealthy countries. Before COVID-19, 87 million people were uninsured or underinsured and 250,000 people died every year from poverty and inequality.

Meanwhile, this year charted the hottest September in recorded world history, in the American West, and we all witnessed entire regions burning and flooding, while our land, water, and air continues to be poisoned by gas, oil, and other fossil fuel, polluting and extractive industries. The health of many millions in this country, and the health of the planet itself, is under assault, and poor and dispossessed people are being hit first and worst. Death haunts us everywhere.

Yet, so many of the critical systems in this country are built on the basis of private profit, not human need. The current crisis should force all of us to deeply consider what the role of government has been in our society and what its role should and could be. And we must also ask what our role can be in charting a new way forward. In the face of mounting suffering, how do we build power to change death-dealing systems into ones that preserve and protect life?

We know that we need a mass movement of poor and dispossessed people, and at the Kairos Center and in the Poor People’s Campaign we know that a movement needs a program. We have that in the Poor People’s Jubilee Platform, a blueprint for the reconstruction of society around the needs of every person, not a wealthy few. During the Health and Healthy Environment session of the “Moral Policy in a Time of Crisis” conference, a powerful panel of leaders examined how we arrived at the current moment, the conditions that we’re confronting today, and how folks are organizing for a genuine vision of health and a healthy environment.

Watch the video of the panel here, and read a summary of the panel discussion below.

How We Got Here: (Bad) Health and an (Un)Healthy Environment

(Dr. Sharrelle Barber is a scholar-activist whose research examines the role of structural racism in shaping health and racial/ethnic health inequities among Blacks in the Southern United States and Brazil.)

With these opening words, Dr. Sharelle Barber reminded us that the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic has proliferated along the fissures of society, both exposing and broadening them:

“The pandemic really exploited the inequities that existed because of systemic racism, systemic poverty, and militarism. We have created systems and structures to maintain this very deadly hierarchy. And so, COVID-19 has exploited what Dr. Mary Bassett [of the Harvard FXB Center for Health and Human Rights] calls the fissures of our society, and really has exposed and laid bare the ways in which we have structured society to be extremely deadly.“

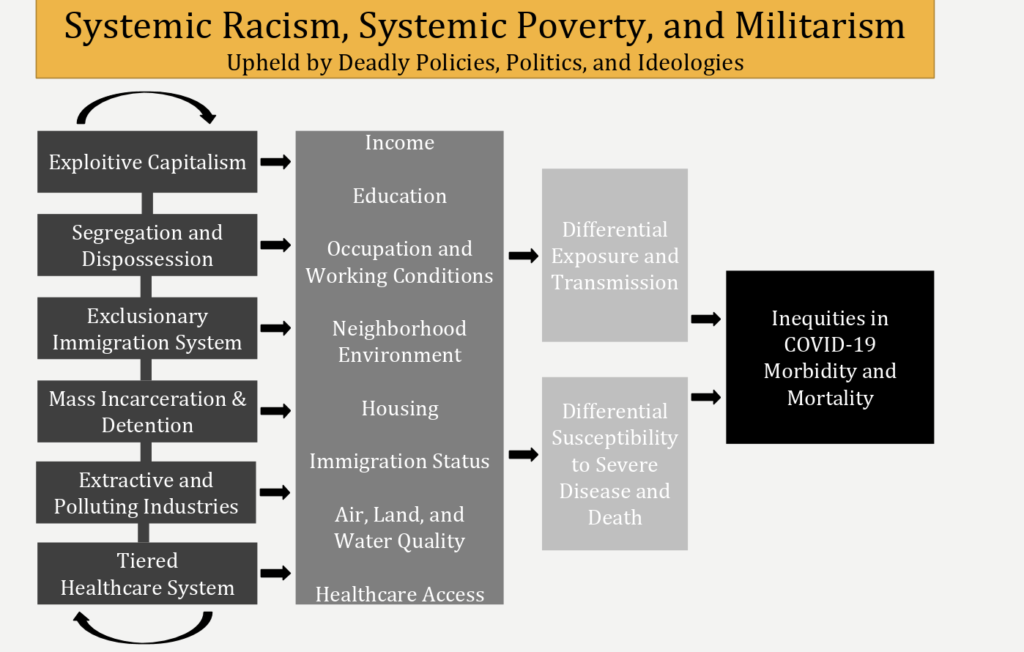

Within the context of exploitative capitalism, Dr. Barber helped identify some of the historic systems and structures that have left American society riven by fissures and vulnerable to high, and highly unequal, rates of sickness and death during the pandemic. These include segregation and dispossession, an exclusionary immigration system, mass incarceration and detention, extractive and polluting industries, and a tiered healthcare system.

For poor people, and poor people of color in particular, these systems and structures, created through government programs and economic policies, have blocked access to many of the essential building blocks of life: clean air, land and water, a living wage and good working conditions, decent housing, healthcare, legal status and more. These, Dr. Barber explained, are what social epidemiologists call the “social and structural determinants of health,” which during the COVID-19 crisis has led to vastly different exposure and death rates. While we don’t have the full numbers yet, we know that poor communities have been hit hardest by this pandemic, and that poor people of color are dying at disproportionately high numbers.

This is not an accident or a stroke of bad luck. When we follow the fissures, we discover the sources of the death that now spirals around us.

(Basav Sen is the Climate Justice Project Director at the Institute for Policy Studies.)

2020 brought not only a vicious and novel virus, but an onslaught of storms and environmental emergencies, including fires across the Western one-third of the country and major hurricanes in the Gulf Coast. These disasters compounded the dangers that poor people already faced in the thousands of American communities that are grappling with extractive and polluting industries and poisoned air, water and land. And reports show a direct link between exposure to pollution and respiratory illness and higher rates of COVID-19 infections and death.

Although these disasters are often described as acts of nature, Basav Sen showed us that the “natural disasters of today are not natural disasters. There’s nothing natural about the fact that there is so much human misery and suffering.” These accelerating disasters are instead what happens when “powerful forces profit from the continuation of toxic and polluting industries.”

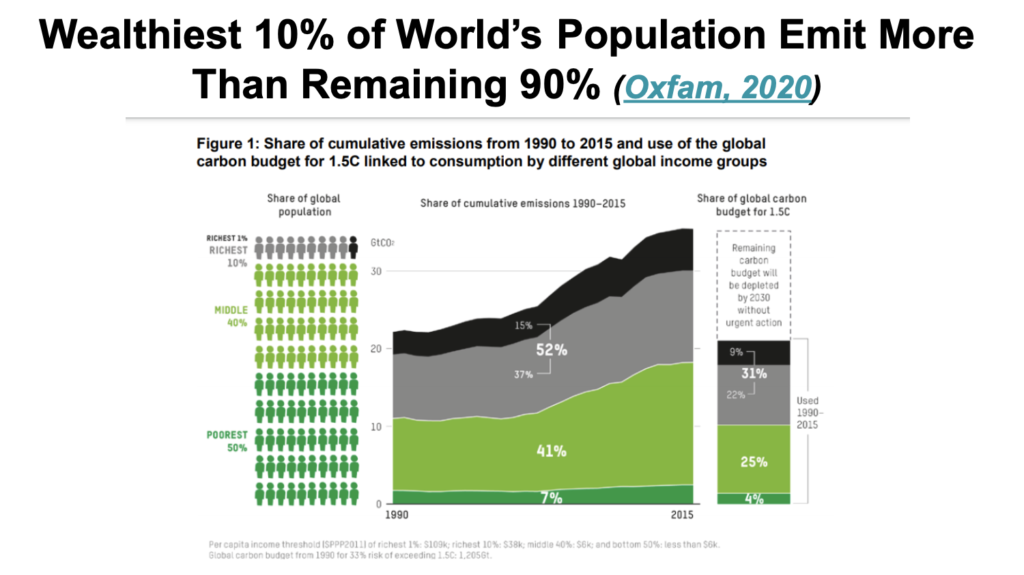

The US government received its first warnings about climate change as early as 1965, but greenhouse emissions from major industries continued to rise largely unimpeded. Over a 52 year period, just 20 companies have been responsible for 35% of global emissions and 100 companies responsible for 70%. Since 1990, the wealthiest 10% of the world has released 90% of carbon output, and the US government and American industry bears disproportionate responsibility.

Basav explained that the industries that produce these emissions have enabled a few people to amass historic levels of wealth. He also showed that these emissions spread along the same fissures as COVID-19 and, until a dramatically different course is charted, they will continue to devastate the planet, hitting the health and livelihoods of the poor first and worst.

From the Frontlines: Kentucky, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania

(Mikaela Curry is a community organizer, environmental scientist and poet based out of North Carolina.)

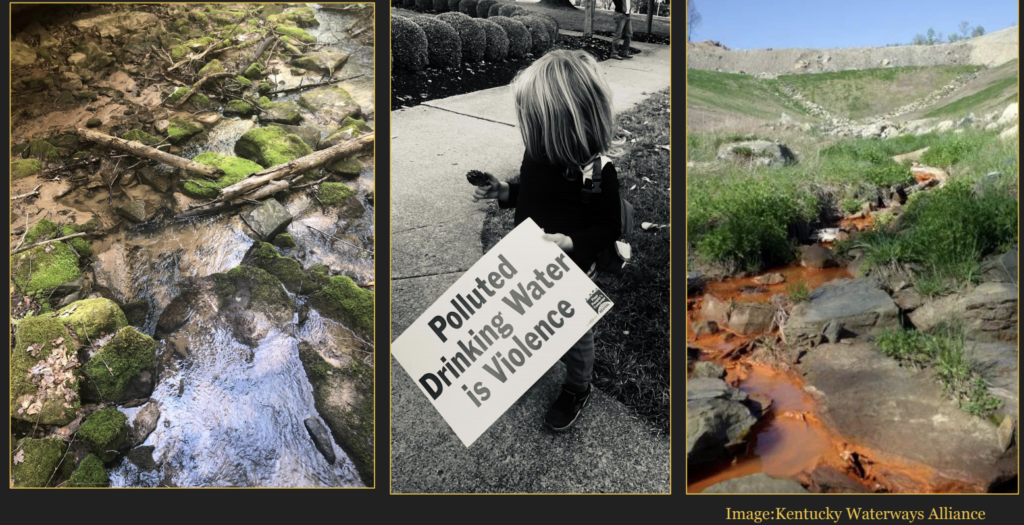

The devastation that Basav described is caused not just by carbon emissions, but by an unyielding, full-spectrum assault on the natural world. Mikaela Curry gave us a snapshot of the carnage in Appalachia, one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems in the Western hemisphere:

“There’s more than 500 Appalachian Mountains that have been removed through [mountaintop removal] and about 300 of those are in eastern Kentucky. A million acres in Kentucky have been affected and over 1400 miles of streams have been destroyed. I have a five year old. And so one of the things that I did is whenever we would pass the [removal] site I would photograph it. And one day as I was taking a picture, my child, from the backseat of the car, said, ‘how long will it take this mountain to grow back?’“

This is a piercing question with an aching answer: the mountains will not grow back. And the common justifications for their removal are wholly inadequate and misleading. Mikaela explained that one of the prevailing narratives in American society is that the extractive energy system is necessary, because it’s the only one that’s affordable. The truth, though, is that the costs of the current system are staggering:

“The public health costs of pollution in Appalachia is $75 billion a year. And at the same time in Kentucky they’re paying direct and indirect subsidies to the coal industry that are over $100 million a year. And in the US at large, direct subsidies to the fossil fuel industry total about $20 billion a year.“

Indeed, the idea that extractive practices are affordable and necessary is a dangerous lie, especially when we come to see both the true costs, socially and economically, and the vast resources that the government could direct toward other, sustainable sources of energy. And Appalachia is not, as it is often painted, an isolated case. Mikaela closed her remarks by reminding us that mountaintop removal in Eastern Kentucky is connected to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, just as the conditions in Flint are inextricable from the worsening situation in countless other communities in this country and across the world. The organized response of these communities, then, cannot be isolated; it must be coordinated and global in scale.

(Sharon Lavigne is a resident of the predominantly African-American Fifth District of St. James Parish, Louisiana. She is the founder and president of RISE St. James.)

One such example of communities fighting back are the poverty-stricken river parishes in Southeast Louisiana, where there are more than 100 petrochemical plants and refineries polluting the air, water, and land, with cancer rates up to 700 times the national average. In St. James Parish alone, where Sharon Lavigne lives, there are 12 industries; one plant for every 656 residents, half of whom are Black.

Sharon founded RISE St. James in 2018 when the governor approved a $9.4 billion plastics project by the multinational giant Formosa Plastics two miles from her home. Sharon explained that many looked at her little community and imagined that no one lives there. And for some who do live beside her on the Mississippi River, the news was received with a tired shrug; what could they do to stop the plant’s construction? But Sharon was awakened: “As I prayed, and I talked to my God, he told me not to sell my home, not to sell my land, and he told me to fight. That’s why I formed an organization.”

RISE St. James has taken the fight to Formosa, packing the audiences of public hearings, holding organizing meetings and marches, working with lawyers to file injunctions, and more. In October 2020, Formosa indefinitely delayed the construction of their new plant until a COVID-19 vaccine is widely distributed. The pandemic may have been the immediate reason for the delay, but the tireless work of RISE St. James and other local organizations has enlisted powerful allies and shone an international light on the poisoning of their communities. Their efforts have also demonstrated the power of poor people taking action together. Now, the fight continues, until, as Sharon is fond of singing, “Victory is mine.”

(Nijmie Zakkiyyah Dzurinko is a working class Black, Indigenous and queer organizer and strategist of over 20 years from Pennsylvania. She is co-founder and co-coordinator on a volunteer basis of Put People First! PA.)

If poor people are being poisoned and made sick, dispossessed and displaced, then we must ask how the poor can unite to change their intolerable conditions. Sharon showed us one example and Nijmie Zakiyyah Dzurinko has made answering that question her life’s work. At the beginning of her remarks, she explained: “my work relates to how we [poor people] come together and build competent, committed, and connected leaders who can have an accurate diagnosis of the problem, so that we can create the right prescription.”

More specifically, Nijmie told us about the recent launch of a new national organizing project: The Nonviolent Medicaid Army of the Poor (NVMA). NVMA emerges from long-term work by organizations like the Vermont Workers’ Center and Put People First! PA, who recognize that healthcare is a unifying issue for poor and dispossessed people that connects to all aspects of their lives, from the crisis of environmental devastation to poverty and systemic racism. A few weeks before the Kairos conference, NVMA organized a series of Medicaid Marches in Vermont, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Kansas, Wisconsin, and elsewhere to demand not only the expansion of Medicaid, but the full realization of healthcare as a human right. This fight is a significant vehicle to help build the organizing power of the poor for the long haul.

Nijmie summed up some of the powerful connections and insights that the marches unearthed:

“We were able to make the invisible visible. We were able to get beneath the surface of things to show the connections between the state violence of the denial of healthcare and the state violence of police violence, when over a quarter of those murdered by the police are in mental health crisis…they’re not separate issues and the Nonviolent Medicaid Army is lifting that up. Workers like Eshawnee Gaston in North Carolina, with Raise Up for 15, spoke about the connection between worker rights and health care. People like Abigail Cruz from Madison, Wisconsin, spoke about…[how] the Medicaid March showed her the commonality actually shared by undocumented folks and citizens in the fight for health care. The Nonviolent Medicaid Army is able to center the fight for health care as a human right.“

The Colossus Can Be Stopped

(Brigitte Kahl is Professor of New Testament/Bible at Union Theological Seminary in New York City and an ordained minister of the Protestant Church of Berlin Brandenburg.)

The connections that the Nonviolent Medicard Army of the Poor is making are moral critiques that cut to the core of how we are organized as a society. At the end of the session, Brigitte Kahl offered another moral critique through a Biblical story of a king who has a nightmare of a golden and metal statue with clay feet: the Colossus.

The Colossus is an inherently unstable structure. It is laden with riches at the top, but its foundation is weak and fractured; there are fissures that run throughout its edifice. Brigitte showed us what happens when we build and rely on structures like the Colossus. She also pointed us toward hope:

“The hope, of course, is the nightmare of the king. For there is a little stone; a tiny piece of rock that comes rolling along right towards the clay feet of the statue. And the dirt, of which the feet of the statue are made, happily leaves its forced union with the iron and embraces the rock. And all of a sudden, the statue has no more feet, and falls down and scatters into a million pieces. You know, you could just imagine the feet walking away from under the statue. It is what we call building a movement. People marching, people on the road, people moving away from the Colossus and leaving it behind. So this is about change, and this change starts from the bottom, but the bottom has to understand its power and we have seen this power here this morning. People who are treated like dirt and the dirt of the Earth itself are rising up against the Colossus. And I think we are at such a kairos moment right now. You know, COVID has done terrible things, and it has taken a terrible toll again from the poor and the people on the margins. But you know, if this is meant to make sense to us we have to…understand that this tiny virus, with all the terrible things it did, it stopped the Colossus for a while.

And the Colossus can be stopped. It can be toppled. So, the system that is built on destroying people and the planet is not infallible. It can be changed. But the people on the margins have to do it. And I think theologically, this is the most important faith act that we need right now. Trust that change is possible. Not just necessary, but also possible, and that the end of capitalism is not the end of the world. So, this is what I take away from this morning. We can topple the Colossus. And if we don’t topple it however, it will bury us underneath it. So we better get moving.“