At the Kairos Center’s October 2020 conference, “Moral Policy in a Time of Crisis,” we heard Kenia Alcocer speak about the history and context of immigrant organizing in Los Angeles. Kenia is an undocumented organizer with Union de Vecinos, the east side local of the Los Angeles Tenants’ Union. She crossed the desert from Mexico with her family when she was three years old and is now a leader in the California Poor People’s Campaign and a steering committee member of the national Poor People’s Campaign.

Immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants, have been particularly vulnerable to the pandemic and economic impacts of the pandemic recession. According to a Public Citizen survey published in September 2020, agricultural workers — many of whom are undocumented — have uninsured rates of about 50%, the highest of all essential workers surveyed. Compared to the national uninsured average of 9%, the Public Citizen survey also found high uninsured rates in other sectors of the essential workforce that are over-represented by immigrant and undocumented workers, including 27% of cooks, 26% of home care workers, 24% of construction workers, 22% of restaurant servers, 15% of meatpacking workers and 12% of both grocery store and nursing workers. Despite their integral role in the economy, undocumented workers are ineligible for health care and other social welfare programs, including the unemployment provisions, stimulus payments and other economic protections of the CARES Act. In fact, the CARES Act also excluded their children — even if they are citizens — from receiving economic aid.

Below, Kenia offers her insight as an undocumented woman, mother and organizer who has been working to improve housing security and living conditions for poor and dispossessed people in Los Angeles. Her struggle is connected to the broader movement that the Poor People’s Campaign is building across the country and that other movements are building around the world. As she said at the Kairos conference, “We’re not just talking about immigration here in the United States, we’re talking about immigration globally…the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is giving hope to movements across the world who are seeing the poor and dispossessed here saying, ‘no more’…Our Jubilee Platform, what we’re asking for, is pretty much what everybody and every movement of the poor and dispossessed around the world has been asking for.”

My name is Kenia Alcocer and I am an organizer with Union de Vecinos, the east-side local of the Los Angeles Tenants’ Union. Because of poverty and systemic racism, undocumented families like mine must work multiple jobs and get paid under the table, and that often comes with mistreatment and discrimination on the job. This difficult situation is made worse by the threat of detention, deportation and family separation. To get by, we have to develop our own survival methods, such as getting together with neighbors to share meals or take care of each other’s kids. Many of us, like myself, have become leaders in movements that unite poor people of all backgrounds to fight — not just to survive another day, but for the right to live a full and vibrant life.

During this pandemic, we are being shown that things we were told were impossible are actually possible. So we are using this moment to open people’s eyes to the possibility of things really changing and for us to push for something that is bigger and better.

I got involved in housing issues when my aunts were in the process of being evicted and were fighting for their homes in the projects in Boyle Heights. This has been an immigrant community for a long time, with Mexicans and other Central Americans, but this used to be a Japanese community. During World War II, they were ripped out of their homes and sent to internment camps. They were completely removed and displaced and that’s when Latino immigrants began moving in. We were only able to come in and settle here because of those racist policies that moved all of the Japanese community out.

“During this pandemic, we are being shown that things we were told were impossible are actually possible. So we are using this moment to open people’s eyes to the possibility of things really changing.”

This became a predominantly Latino community in the early 1970s and 1980s and that was also related to trade policies that were displacing Mexican communities. NAFTA was passed in 1994 and that escalated things. Rural Mexican communities were forced to leave their homes and come North to look for work and jobs — they were no longer allowed to do the farming they had been surviving on in Mexico, with the produce they had been always growing. Instead, they were being forced to grow whatever the government was telling them they needed to grow. Because of those policies, a lot of the tortillas in Mexico are no longer made with Mexican corn. They’re made with American corn. This is how our community was built and what shaped the development of our community.

Now, because we are a predominantly Mexican immigrant community, there aren’t a lot of homeowners here. Many of us are poor and low-income, even though we are working multiple jobs, and we’re tenants in low-income housing projects and apartments.

These projects used to be mainly white, but in the early 1990s, the federal housing program Hope VI was passed and began converting public housing into “mixed income” housing. Housing projects were being demolished. Our housing projects in Boyle Heights used to be the biggest housing project west of the Mississippi, but over 2500 families were displaced because of Hope VI. So our community decided to fight back and organize against the demolitions and we were able to get some families back into their housing. These are the roots of Union de Vecinos and all along, we’ve been confronting not only racist policies, but policies attacking the poor.

One of the things we realized was that we needed to go outside the housing projects and organize in the neighborhood, because a lot of our community members were being displaced into the private housing sector. State laws were taking away our driver’s licenses. Every Friday in the city of Maywood, the city put up these “sobriety checkpoints,” but they were also taking and impounding cars from undocumented immigrants who didn’t have licenses. Towing companies were making millions of dollars every year from this. This was another policy we started organizing around and we were able to get rid of the checkpoints in Maywood. In fact, Maywood later declared itself a sanctuary city. It was the first sanctuary city in the country and we were at the forefront of shaping policy and a national conversation about immigrant rights through our organizing.

Tenants in Maywood were able to get funding to improve water quality and pass “just cause” laws to protect tenants from being evicted. And then, we started to see more attacks — we were called communists, investigated by the FBI, and our people were run out of the community. This is when we realized we cannot be isolated, just on our own, fighting for our own. We need to integrate ourselves into a broader movement of the poor and dispossessed across the country. This is why we, even as undocumented people who cannot vote, still did “get out the vote” work during the election this year and in previous years, knocking on doors, talking to voters, ensuring that voters are coming out to vote for their needs and for the power of the poor and dispossessed. That also includes us.

We know that housing is not just about housing or the places where we are living. In fact, when it comes to immigration, we’re not just talking about immigrants here. We have people on the border right now, on the Mexican–U.S. border seeking refugee status. And the reason why a lot of Central Americans are coming here is because their natural resources are being taken away by transnational companies. This is no longer about immigration, it’s about being refugees: refugees from war, refugees from hunger, refugees from violence.

Right now, we are entering the holiday season and we must remember what Mary and Joseph were doing when they were leaving their home: they were trying to protect their son. This is what immigrants are doing every day. This is what homeless people and poor people are doing every day. They’re trying to protect their kids. My mother crossed a desert to give me a life with dignity and basic human needs — a home, food and education.

“We’re not alone. We’re not alone in our state. We’re not alone in this country. We’re not alone in this world.”

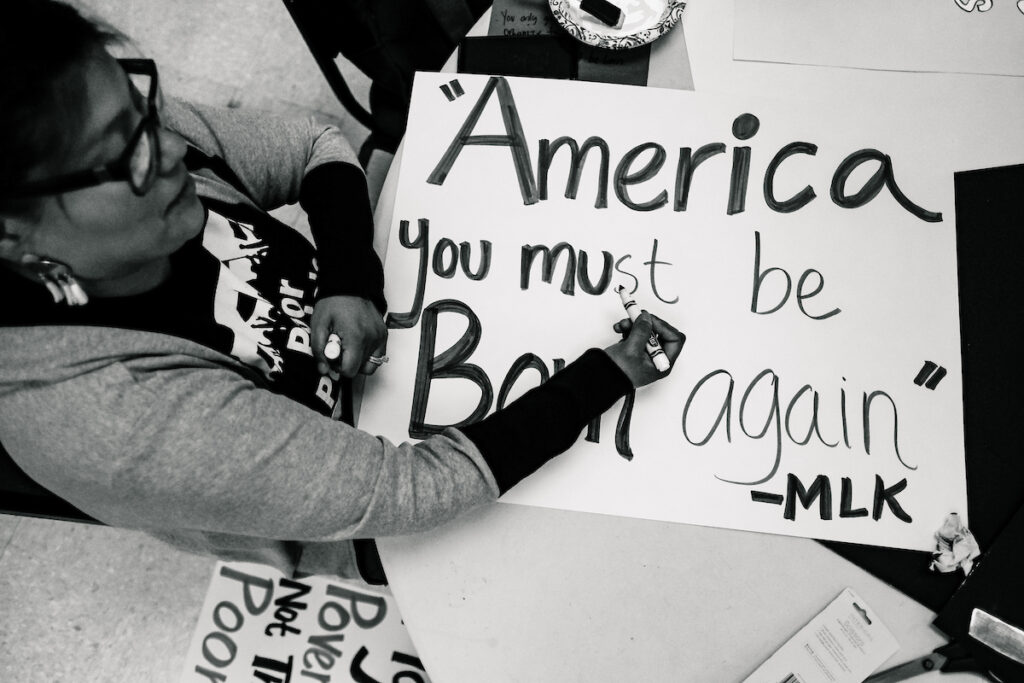

Every time poor people are organizing, every time we’re distributing food, knocking on doors, sharing information, studying and learning together, this is what we’re doing. We’re standing up for ourselves and our community. And I know that the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is giving hope to movements across the world who are seeing the poor and dispossessed here saying, “no more.” When we’re talking about safe housing or water rights, we are joining with poor people in other countries who have lost their land and water rights to multinational companies. When we’re talking about better air quality, we’re talking about better air quality for everybody. Our Jubilee Platform, what we’re asking for, is pretty much what everybody and every movement of the poor and dispossessed around the world has been asking for.

So while we are building this Campaign here, we are also joining these global movements of the poor. We’re not alone. We’re not alone in our state. We’re not alone in this country. We’re not alone in this world.