On September 23, the Kairos Center hosted its first Survival Summit on Food Justice. The name of the series is a reference to the 1989 “Up and Out of Poverty NOW!” Survival Summit that was organized by the National Welfare Rights Union, National Union of the Homeless and the Anti-Hunger Coalition to connect emergent efforts around housing, welfare and food security and build up their collective power. This is the lineage and history of the Kairos Center that we carry forward today in this current series, where we highlight key struggles and issues facing the nation’s 140 million poor and low-income people in this country.

This summit was the first in a series focusing on how people are surviving during and after the COVID-19 global pandemic. During the day, sessions were held by organizing groups from across the country on issues relating to food justice, and that evening the Kairos Center organized a panel discussion with scholars, policy experts and organizers working to end hunger. Below are some of the insights shared, and if you have time, watch the full panel discussion here.

Changing the Narrative Around Hunger

The mission of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival (PPC:NCMR) is bold and multi-faceted, but at the core of its agenda is shifting the narrative around poverty and building the organization and power of the 140 million. The prevailing narrative says poverty is the fault of individuals and their choices, that the number of poor and low wealth people is smaller than it actually is, and that poverty persists because we as a society have not yet progressed far enough to meet the needs of everyone. Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, Kairos Center Director and co-chair of PPC:NCMR, framed the conversation around countering this narrative:

“This false moral narrative blames poor people, hungry people for all of society’s problems, pits us against each other and feeds us the lie that this is as good as it gets. It feeds us the lie of scarcity, when in fact we’re actually living in a world of beautiful, amazing abundance. There are 140 million people in the richest country in human history, who are poor or one emergency – one job loss, one healthcare crisis, one storm – from economic ruin. And we throw out more food than it takes to feed every person, not just in this country, but in this world, and yet, 51% of our kids are going to bed at night in food insecure homes.”

Alison Cohen, Director of Programs at WhyHunger, has worked for decades in the fight against hunger and identified the false narratives that push against the food justice movement. She challenged the widely accepted value of “rugged individualism” – or the belief that, if a person works hard enough and “pulls themselves up by their bootstraps,” they can escape poverty. This myth ignores how corporate greed and government inaction perpetuate hunger. Indeed, over the past 40 years, worker productivity has risen over 60%, but average compensation has only risen 17.5%. Despite the rising cost of goods and services, the federal minimum wage has not increased since 2009. And failed economic policies have resulted in the exponential growth of the richest Americans’ wealth amid the steady decline of wealth for low-income families.

One of these failed economic policies that Alison directly addressed was The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, more commonly referred to as welfare reform:

“The 1996 Welfare Reform Act overhauled the nation’s welfare system. The Act was both a result of and an attempt to really cement the dominant cultural lens that welfare dependency was a scourge on the American worker, and that it could be eliminated by these laws that would promote work and marriage. And it was rooted in this narrative of rugged individualism…Years later, studies came out showing that, while the number of welfare recipients did decline, the number of families in poverty actually increased because of welfare reform. In other words, incentivizing work and marriage didn’t end poverty, because it turns out that work and the nuclear family do not correlate to higher income.”

Another dominant myth Alison identified is the cultural acceptance that hunger and food insecurity are fixed parts of our society. This myth legitimizes an inadequate solution to hunger, pointing to charity and the “generosity” of the rich to save us:

“This narrative undergirds the idea that it’s really up to these good-hearted volunteers and generous corporate actors to address hunger by capturing food waste and distributing it to soup kitchens and pantries. ‘Surplus food for surplus people,’ some people say, which also serves to keep this food waste out of landfills, and so it’s actually also being framed as a solution to climate change. It may be necessary to meet immediate needs, but this is really a false solution to hunger and forces us to accept it, rather than end it.”

Rev. Liz continued with this thread, challenging the absurdity of our current food system and grounding us in the truth that everyone has a right to food. She highlighted how the passage from Matthew 26:11 is often cited as biblical justification to justify poverty. After Jesus’ disciples question the presence of a poor woman anointing his feet with oil, Jesus says, “You will always have the poor with you. But you will not always have me.” Out of context, this passage seems to suggest that Jesus deems poverty unsolvable and that maintaining faith in him is our mission on Earth. But in the verse prior, Matthew 26:10, Jesus asks his disciples, “Why do you trouble the woman?” Jesus’ question speaks to us right now, in 2021: why are we troubling the poor? Why do we pay starvation wages to the very laborers who produce our food? Why do the super wealthy hoard their wealth when we have the means to give everyone enough to live? Why do we judge the poor for being in situations our cruel society has forced them into?

Rev. Dr. Theoharis offered a new perspective in that, “Matthew 26:11 is to be read as a warning (not a prediction) that the perils of disobedience to God’s commandments are poverty and inequality, and as Jesus’s call to the disciples to take up the struggles of the poor for economic and social justice even after his death… It is possible, in fact it is required by God, that we end poverty.”

In this same biblical passage, Jesus’ disciples question why this woman possesses such expensive oil. There are many today who police the poor and question why they possess and desire nice things. Reverend Liz spoke to this point:

“One of the references of that anointing is about how the poor deserve good things, beautiful things, luxurious things. And I think we need to get away from the idea that we can survive on a couple dollars a day or that we need just a little more food stamps or slightly better welfare benefits. No. We want all of our needs met, fully, and we can do that. And we can do that in a sustainable way.”

In the food justice movement, we must constantly be aware of these persisting myths by intentionally identifying and countering them.

Why are People Hungry?

Raj Patel is an award winning author, filmmaker, and academic in the food justice movement. His most recent book, Inflamed, reveals the links between health and structural injustices. In his comments during the summit, he pointed to the root causes of hunger worldwide, calling them the three C’s: climate, conflict, and capitalism. According to the Climate Vulnerability Monitor developed by DARA, an independent, international organization committed to improving the quality of humanitarian effort, in 2012 there were 225,000 hunger-related deaths worldwide due to climate change every year, and over 200 million people were estimated to suffer from food insecurity in lower-income countries. By 2030, the death toll is projected to climb to 380,000 per year, and the communities hardest hit by hunger are the poorest and the least responsible for climate change. Through war and conflict, farmers are driven off their land by militias before they can harvest. In 2018, the United States had positioned 750 military bases in over 80 foreign countries, colonies, and territories. Because the US military claims its environmental laws do not apply overseas, they often endanger the local people’s water and farmland by dumping hazardous and toxic materials into the earth. In fact, the Department of Defense is the single largest institutional polluter in the world.

Raj discussed the relationships between the three “Cs,” and how they manifest in our food system:

“This is a country that was built on a food system that involves stolen land and stolen labor and stolen people. The United States of America couldn’t be the United States of America, were it not for the vast theft of land from the people who were here first, and then the application of labor from people who are trafficked across the Atlantic, and whose descendants remain in modern terms, substantially unfree. The story of agricultural labor in America is a story really about stealing. It’s about stealing work. It’s about stealing the bounty of nature. It’s about stealing land.”

“This is a country that was built on a food system that involves stolen land and stolen labor and stolen people.”

-raj patel

Raj challenged us to consider how, despite the reality that there’s more food per person now than ever in human history, billions of people worldwide are food insecure. Raj shared that over a third of the world’s population cannot afford to eat a healthy diet. The problem is not food scarcity, the problem is our cruel capitalist system:

“The way we distribute food is on the basis of the ability to pay. If you have money, you can eat whatever you like. And if you don’t have enough money, then you either starve or you eat a diet that is not good for you.”

Today, a new driver of hunger has emerged: COVID-19. Amid stay-at-home orders and drastic shifts in economic demand, millions of people have lost their jobs and essential workers continue to risk their lives for inadequate compensation. Despite the USDA’s claim that food insecurity in 2020 remained at similar levels from 2019, Alison presented the real numbers on food insecurity during the pandemic:

“For those of us working on the front lines of emergency food distribution during COVID, that [USDA] headline did not match up with the experience of folks who are shifting logistics towards touchless services or moving staff from policy and organizing to handing out food to folks that were staying in the long lines. In fact, we saw that the need was so large that most operations wound up turning people away. They just simply weren’t able to get enough food..

…[A] closer look at the data – coupled with some of the surveys that were done by the Census Bureau during COVID – tell a different story. And I think this is where we have an opportunity, as Raj was saying, to really lean into a different narrative. Food insecurity actually doubled at the height of the pandemic. There were many people I know that were, for the first time, finding themselves in food bank lines. The real reason we’re ending this year with a relatively stable food insecurity rate compared to 2019 is that direct cash payments helped the millions who were newly in financial crisis during COVID.”

Policies like direct cash payments through stimulus checks and the Child Tax Credit did not exist in America before COVID-19. They have proven to be life-saving for poor and hungry people, but more must be done. Maureen Taylor, state chairperson of the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, imagined alternatives to our current food system. She began by sharing the history of food stamps in America or SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program):

“Near the end of the Great Depression, it was discovered again that young men being readied for war were not fit for duty, because so many were suffering from malnutrition. Food Stamps came about in 1939, as these troops needed to carry 30 or 40, or 50 pounds of military equipment, and they just couldn’t do it. The point is, there is a political rationale for why food injustice exists in America, even alongside these programs.”

Today, the average family of three, one adult with two children, receives just $7.90 per day in SNAP benefits – a figure that hasn’t changed much in over 40 years. Many formerly incarcerated people, undocumented people, and some legal immigrants are generally ineligible or have restricted eligibility for SNAP. Food banks and soup kitchens have become primary sources for food, rather than emergency resources.

Creating a world without hunger, Maureen argued, starts with ground level involvement. The Michigan Welfare Rights Union engages with their community, hearing the stories of those who are behind on rent or have had their SNAP benefits cut off. From there, they identify policy proposals that will ensure their survival is not a question, but a certainty. Reflecting on these conversations, Maureen shared what she believes food justice looks like:

“What [food justice] would mean is that a person or a family with limited resources would not be punished because they were poor… Their food stamps would be open ended, meaning that whatever you purchase, you would be reimbursed by the state or the federal government with no limitations. Full justice would mean that food pantries and soup kitchens would operate on an emergency basis. For instance, if a house caught fire, the food cart of the food pantry would be available to substitute a meal for that evening. And the family would be eligible for ongoing meals as needed, with no restrictions.”

“What [food justice] would mean is that a person or a family with limited resources would not be punished because they were poor.”

-Maureen Taylor, Michigan Welfare rights union

In this world, and especially in this country, our capacity to grow food has never been higher. There is no reason why every person on Earth cannot have their food needs met. Only when our food system, as Maureen says, “offers sustenance based on need, and not on the ability to pay,” will we end the root causes of hunger for good.

Organizing to End Hunger

The Michigan Welfare Rights Union is part of a long tradition of groups engaging in projects of survival. As indicated above, our society organizes food assistance around scarce government aid and proving you are “deserving” of that aid by your ability to jump through bureaucratic hoops. While charities are seen as safety nets for those who can’t receive government aid, in reality, many millions of people rely on charities as a primary food source.

At the same time, mutual aid projects recognize that government action is slow and the charity model is inadequate and sometimes inequitable. Instead, they utilize networks and resources within the community to meet their needs. Mutual aid projects are organized around the idea that the government will not save us; only we can save ourselves.

While these projects do a good job of meeting immediate needs, this moment demands more. We must engage in projects of survival to awaken a political consciousness, build political power, expose the larger moral failures of the dominant narratives, and move society in a direction that lifts from the bottom. The Depression-Era Unemployment Council’s eviction and utility support networks, the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program, and the National Union of the Homeless’ shelters and vacant home takeovers are all examples of projects of survival that we learn from and build upon today. As Noam Sandweiss-Back has written:

“At the very core, these projects are woven into a political and moral imagination that emphatically believes in the power of poor people to be agents of change, not just subjects of a cruel history.”

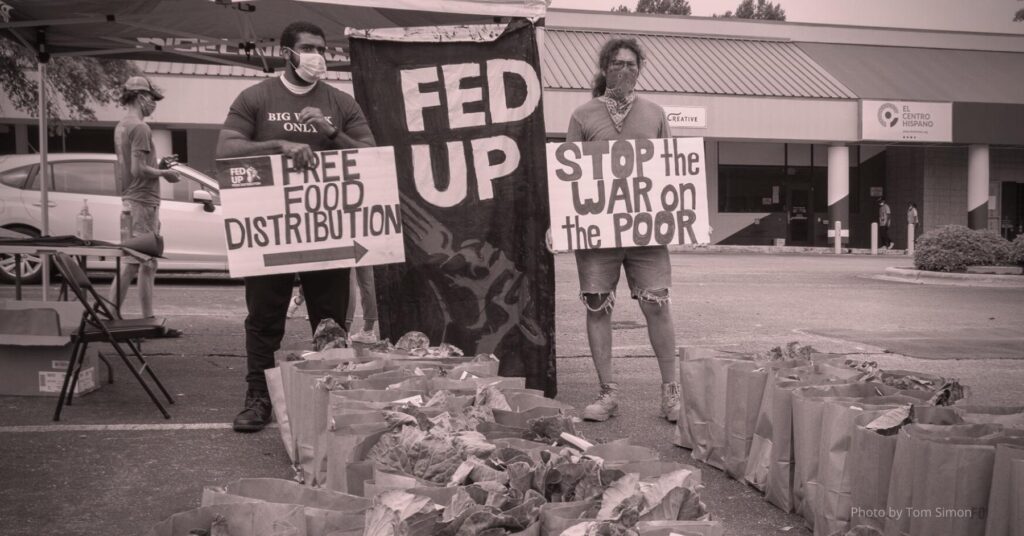

Keith Bullard is a coordinator of NC Raise Up and an organizer for Fed Up, a project of survival meeting the food needs of the people in Durham, North Carolina. Every other Friday, they create food distribution centers and mobile food deliveries to local residents. Drawing on agricultural and other networks, Fed Up fills and distributes hundreds of bags of groceries to anyone who needs it. Fed Up isn’t just meeting the community’s survival needs. They are challenging the narrative that hunger is just a part of society. As Keith questioned:

“Why are people hungry in the first place? Why do we have to be open on this Friday delivering these things when there’s so much food? There’s enough food for everyone to be able to have healthy food and enough food in general. Really, the first myth we have to confront is a charity mentality that accepts the system, rather than trying to change the system that causes hunger in the first place.”

“Really, the first myth we have to confront is a charity mentality that accepts the system, rather than trying to change the system that causes hunger in the first place.”

-Keith bullard, NC Raise up, fed up

In addition to providing food, Fed Up includes political literature in their bags to get participants asking these same questions and learning from freedom fighters around the world who have opposed systems of power that keep people hungry. Organizers have intentional conversations to understand everyone’s unique situation and to invite them to engage in regular political discussions. They’re meeting survival needs, building community, and cultivating an educated base of people ready to challenge the dominant false narratives and organize against it. As Keith said:

“In this broader community building setting, where we are talking about issues that impact our community, we make sure to say that we’re fed up with the system. We’re fed up with insecure housing. We’re fed up with the lack of health insurance, health coverage. We’re fed up with low wages. We’re fed up with the lack of protections when it comes to COVID and other unsafe working conditions.”

Lu Aya, a cultural worker and organizer with the Peace Poets, spoke to the importance of art as an organizing strategy and survival strategy. Lu believes that art and songs made by directly impacted people can spark change in ways that words alone cannot:

“For me, as a cultural worker, writer, as a musician, as an artist, as a poet, I’m looking to our community, who have powerful truths to share. And the story we have to bring to the streets is from the person picking tomatoes to the person next to them telling the story of dignity, of justice. When we’re in that circle, we look at each other, and we begin to compose together.”

History has proven that when we organize, we win. Every major victory for poor and low wealth people was achieved through organizing. Rev. Liz reflected on these wins:

“Where we get programs like HeadStart or a policy like the Child Tax Credit, isn’t from policy wonks. Welfare rights leaders have been advocating and pushing for these things for decades. And any win that we have is because there are people that are impacted, who are out there pushing, pushing, pushing, being persistent, and winning, and saying, ‘There is victory here in this struggle and in our coming together around these issues we share in common.’”

The Call to Action

These Survival Summits are not just moments to share strategies and lessons from our work on the ground, but also a place to build power toward our mission of eradicating poverty by lifting from the bottom. And we must lift from the bottom. The 140 million poor and low wealth people of our society know their survival needs the best, and they must be the ones leading this movement. When asked what more must be done, Rev. Liz made a powerful call to action:

“In 1967, when Dr. King writes, ‘Where Do We Go from Here, Chaos or Community?’ he is speaking to a critique of inequality, and capitalism, that everyone here is speaking to. He says, ‘the contemporary tendency in our society is to base our distribution on scarcity, which has vanished, and to compress our abundance into the overfed mouths of the upper classes, until they gag with superfluidity. If democracy is to have a breath of meaning, it is necessary to adjust this inequity. It is not only moral, it is also intelligent.’

…When I think about the question of moral and intelligent leadership, it leads me to the grassroots leaders who are fighting every day across this country, across this world. Leaders like we’ve seen this evening in Maureen Taylor and Keith Bullard and Lu Aya and Alison Cohen, who wake up every day, in different situations in different settings and think, ‘What is it going to take for us to not just meet people’s immediate needs, but to actually build a movement?’

“A movement is the only thing that has ever been powerful enough, influential enough, big enough, beautiful enough to be able to actually overcome deep poverty, deep inequality, and grave injustice.”

-Rev. dr. liz theoharis

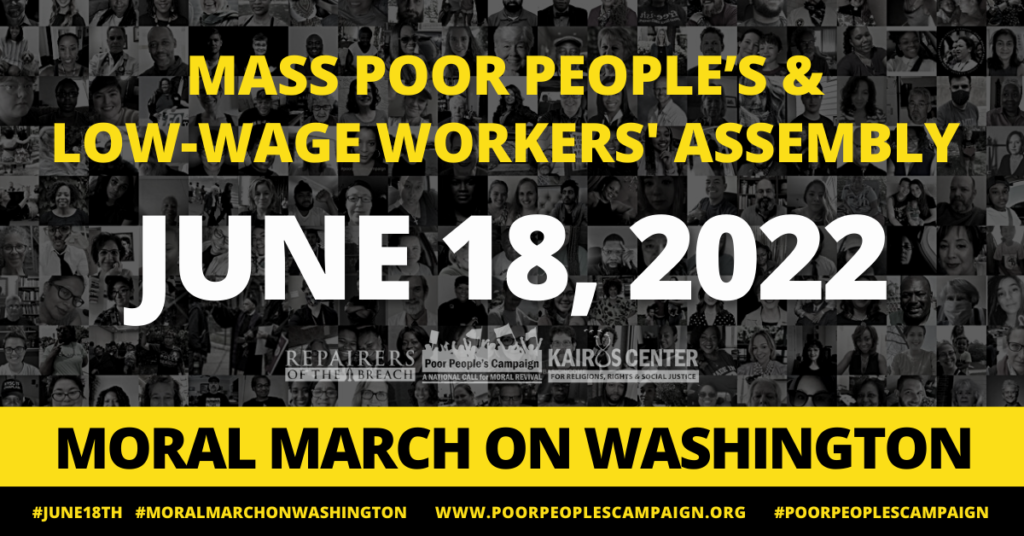

And a movement is what we are building. Right now, the Poor People’s Campaign, A National Call for Moral Revival and its 45 state coordinating committees are organizing a March on Washington on June 18, 2022, demanding our nation’s leaders listen to the needs of the 140 million poor and low wealth people. Rev. Dr. William Barber II, Co-Chair of PPC-NCMR, has said this march will “not be a day but a declaration.” Our movement challenges us to think beyond the passage of one small bill in Congress. Our movement will challenge us to look even beyond our gathering next summer. We will build on the power of this Survival Summit to organize our communities, build our networks, strengthen our projects of survival or perhaps start new ones, and continue to move forward together and not one step back.