The 50th anniversary of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Beyond Vietnam” sermon from the Riverside Church fell just before Holy Week. His speech marked one year before his assassination, and his refusal to remain silent about the triple evils of war, racism and poverty in “Beyond Vietnam” must be remembered in relationship to that violent silencing.

With us now in the midst of Holy Week, it is hard not to notice parallels between the lives, missions, and legacies of Jesus Christ and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. By looking at these holy and prophetic leaders next to each other, we can learn something about both of them. I see five related actions, commitments and experiences that help us understand their ministries and what they are calling us to do today:

- The sanitation workers strike and Poor People’s Campaign Mule Train to Washington with the Palm Sunday entry into Jerusalem;

- The turning over the tables in the Temple and the call for massive civil disobedience – the disruption of the social order and practicing of civil disobedience that both leaders called for;

- The prophetic teaching and preaching Jesus and King did;

- Their commitment to the eradication of poverty, critique of charity, and insistence on the leadership and agency of the poor themselves;

- And their isolation, crucifixion, and resurrection at the end of their lives.

The conclusion I wish to draw from these parallels is that both Jesus and King were revolutionary leaders. They were prophets who committed their lives to building and leading a social, political, economic and spiritual movement to raise up the poor and marginalized and to abolish poverty and inequality and all forms of oppression. In fact, I want to assert that like Rev. Dr. King’s last campaign, the Poor People’s Campaign, Jesus Christ was also leading a Poor People’s Campaign and calls his followers to do the same.

Rev. Dr. King saw that Jesus’ spiritual and political leadership is inseparable:

I know a man—and I just want to talk about him a minute, and maybe you will discover who I’m talking about as I go down the way because he was a great one. And he just went about serving. He was born in an obscure village, the child of a poor peasant woman. And then he grew up in still another obscure village, where he worked as a carpenter until he was thirty years old. Then for three years, he just got on his feet, and he was an itinerant preacher. And he went about doing some things. He didn’t have much. He never wrote a book. He never held an office. He never had a family. He never owned a house. He never went to college. He never visited a big city. He never went two hundred miles from where he was born. He did none of the usual things that the world would associate with greatness. He had no credentials but himself.

He was only thirty-three when the tide of public opinion turned against him. They called him a rabble-rouser. They called him a troublemaker. They said he was an agitator. He practiced civil disobedience; he broke injunctions. And so he was turned over to his enemies and went through the mockery of a trial. And the irony of it all is that his friends turned him over to them. One of his closest friends denied him. Another of his friends turned him over to his enemies. And while he was dying, the people who killed him gambled for his clothing, the only possession that he had in the world. When he was dead he was buried in a borrowed tomb, through the pity of a friend.

In this profile of Jesus, King concisely summarizes the centrality of liberation, equality and prosperity in the gospel and among the followers of Jesus.((“Another presupposition for election as popular king is an organized following, indeed, a fighting force” (Horsley and Hanson, Bandits, Prophets, Messiahs, 95).)) This portrait aligns with the one in the Gospel of Mathew where in the Passion Narrative and other stories from his ministry, Jesus is understood as a threat, an alternative “King of the Jews” by the ruling authorities and elites. Biblical scholars Richard Horsley and John Hanson confirm an overtly political meaning to Jesus as “Christ/messiah.” They have found that in the period when Jesus lived there were other popularly acclaimed kings who challenged the ruling literate elites.((It is questionable how connected to justice-making and popular movements the “anointed of Yahweh” were. Hanson and Horsley write that although they originated from popular traditions of kingship, those in power in ancient Israelite society coopted the concept and connected it to the Davidic king: “In sharp contrast to popular kingship, there emerged an official royal ideology, probably during the regimes of David and Solomon. The understanding of the king as ‘the anointed of Yahweh” in all likelihood originated in popular traditions of kingship. However, in the royal psalms, liturgical expressions of the official royal ideology, ‘the anointed of Yahweh” became identical with the Davidic king” (Horsley and Hanson, Bandits, Prophets, Messiahs, 96-97).))

Before and after Jesus of Nazareth…there were several popular Jewish leaders, almost all of them from the peasantry, who, in the words of Josephus ‘laid claim to the kingdom,’ ‘donned the diadem,’ or were ‘proclaimed king’ by their followers. It thus appears that one of the concrete forms which social unrest took in the late second temple period was that of a group of followers gathered around a leader they had acclaimed as king.((Horsley and Hanson, Bandits, Prophets, Messiahs, 88.))

After the defeat in the Jewish Wars of 66-70 CE—which Jews living in the ancient near east considered another failed messianic movement—there was great need for Jesus’ followers and the Matthean community to locate leaders who would intervene on behalf of the majority poor and dispossessed.((Richard Horsley asserts numerous messiahs arose to this challenge: “Although Judean ruling and literate circles had no interest in the messiah, it was clear from the accounts of the Judean historian Josephus and other sources that the Judean and Galilean peasants produced several concrete movements led by a popularly acclaimed king or prophet. These concrete movements that assumed social forms distinctive to Israelite tradition, moreover, proved to be the driving forces of Judean history during the crises of late second-temple times” (Horsley and Hanson, Bandits, Prophets, Messiahs, xiii).)) Jesus is such a leader and so much more: he’s a popularly acclaimed king who comes to address the social-economic crises of the late second-temple; he’s crucified by the ruling elite but still resurrected by the God of Israel, becoming the founder of such a social movement of the poor to right the wrongs of society; he is a Savior, whose redemptive love and prophetic witness still hold great power for millions worldwide.

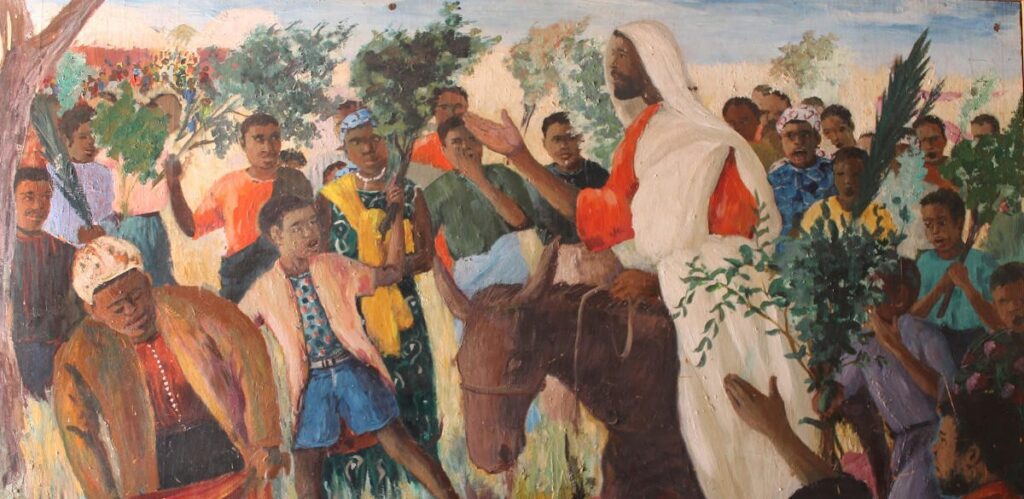

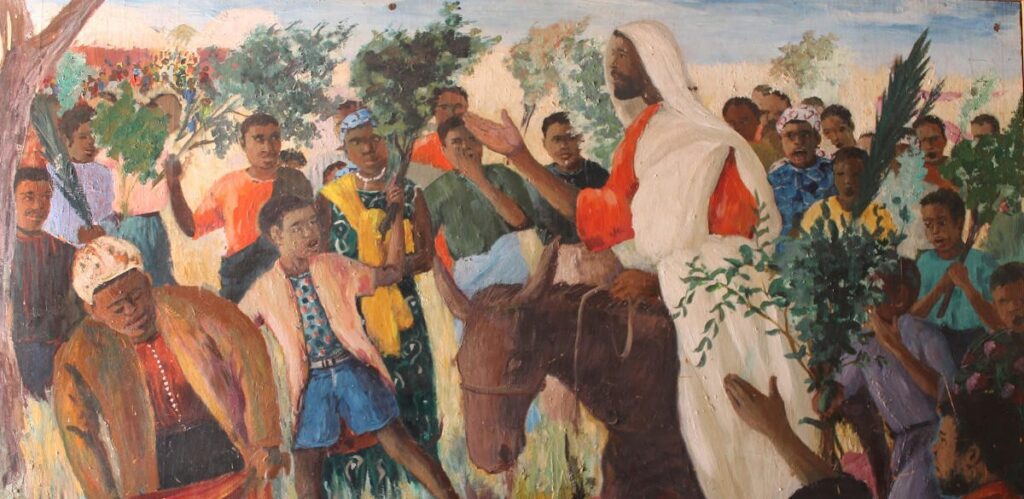

With this context in mind, the events of Jesus’ last week have new meaning. There are actually two processions on Palm Sunday. Caesar’s imperial guard enter occupied Jerusalem on horses and chariots as a military force to control and discipline the Jews during Passover, a period known for protests. Jesus enters Jerusalem on a borrowed donkey—not a chariot, or even a horse. It is a parallel to and mocking critique of the procession of Caesar’s imperial guard.

Once Jesus enters Jerusalem, he goes to the Temple to check things out. He returns to the temple on Monday and causes a scene there, stopping the buying and selling and pronouncing it a den of robbers, a safehouse for people who are stealing and cheating the poor. The Moral Movement likes to call the turning of the tables the first Moral Monday. What Jesus does in the temple is civil disobedience. And when his teachings and healings are combined with these acts of civil disobedience, it is determined that he must be crucified.

This is where I see a parallel with Rev. Dr. King and the Poor People’s Campaign. The last campaign and march that King participated in was the Memphis sanitation workers strike. King was invited to and resolved to help lead this march. There aren’t two parallel marches in Memphis, but the Memphis police and National Guard monitor the march and manage the crowd at this procession.

And the Poor People’s Campaign that King called for began with a mule train procession in Marks, MS. Marks was in the poorest county in the US in 1968, just like Galilee was one of the poorest places in the Roman Empire. The mule train procession from Marks traveled to Washington, DC, the political, economic and — one could argue — religious center of the US, just like Jerusalem was the center of Judea within the Roman Empire.

King was assassinated before the mule train began, but they carried out his vision of setting up a Resurrection City (notice the religious language) on the lawn of the capital. From this tent city, poor people of all races left every day to go protest and do massive civil disobedience in hospitals, at the department of agriculture and other temples of our day.

When King began planning this campaign, he described its strategy in the Massey Lectures in December 1967.

The dispossessed of this nation — the poor, both white and Negro — live in a cruelly unjust society. They must organize a revolution against the injustice, not against the lives of the persons who are their fellow citizens, but against the structures through which the society is refusing to take means which have been called for, and which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty. The only real revolutionary, people say, is a man who has nothing to lose. There are millions of poor people in this country who have very little, or even nothing, to lose. If they can be helped to take action together, they will do so with a freedom and a power that will be a new and unsettling force in our complacent national life. Beginning in the New Year, we will be recruiting three thousand of the poorest citizens from ten different urban and rural areas to initiate and lead a sustained, massive, direct action movement in Washington. Those who choose to join this initial three thousand, this non-violent army, this ‘freedom church’ of the poor, will work with us for three months to develop non-violent action skills.

The moral action that Dr. King called for and planned for the Poor People’s Campaign was deeply rooted in a moral analysis and articulation of the three evils of racism, militarism and poverty in his time. Indeed, both King and Christ disrupt the social, political and economic order. Both Jesus and King preach and teach their followers to do the same. Both call for a moral revolution of values.

In the Bible, after Matthew 21 tells the story of the triumphal entry into Jerusalem and the civil disobedience in the Temple, Matthew 22-25 includes passages about paying taxes, rejecting idolatry, loving God and your neighbor, and treating the poor as one should treat God. In particular, Matthew 23 has a biting critique of the hypocrisy of religious leaders and a condemnation of oppressing the poor and marginalized.

Matthew 23 includes:

Then Jesus said to the crowds and to his disciples: ‘The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat. So, you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach. They tie up heavy, cumbersome loads and put them on other people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to lift a finger to move them.

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You shut the door of the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces. You yourselves do not enter, nor will you let those enter who are trying to.

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You travel over land and sea to win a single convert, and when you have succeeded, you make them twice as much a child of hell as you are. Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You give a tenth of your spices—mint, dill and cumin. But you have neglected the more important matters of the law—justice, mercy and faithfulness.…You strain out a gnat but swallow a camel.

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead and everything unclean. You build tombs for the prophets and decorate the graves of the righteous. And you say, ‘If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.’

Rev. Dr. King also takes on the hypocrisy of our politicians and religious leaders, suggesting that we are called to live another way. He particularly does this in his “Drum Major Instinct,” “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” “Trumpet of Conscience” and “Staying Awake” sermons. In “Beyond Vietnam” he preached:

We must rapidly begin the shift from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-oriented” society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered. A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. On the one hand we are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside; but that will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life’s highway.

I see further connections between Jesus and the Jesus movement and Rev. Dr. King and the Poor People’s Campaign in Judas’ betrayal of Jesus for material gain, Jesus’s crucifixion at the hands of the Roman Empire as a rebel and revolutionary, the resurrection of Jesus and the breaking open of the tombs and resurrection of the saints — the fallen fighters from freedom struggles of the past who are resurrected alongside Jesus to continue the fight. I hear echoes of this story in King’s assassination, the abandonment of King’s friends who were unable to carry the Poor People’s Campaign to a successful conclusion, and a rebirth of that campaign by poor people 50 years later, including people who have been fighting to end poverty from Marks and Memphis and Nashville and Montgomery and Raleigh for the past 50 years. There is a resurrection of the saints happening today, as poor people are joining together to re-ignite the Poor People’s Campaign.

Indeed, grassroots communities are building this new Poor People’s Campaign. It includes families still living with poisoned water in Flint, Michigan, homeless encampments in California and Oregon and Washington State, journalists and impacted residents in the Gulf Coast more than 10 years after Hurricane Katrina and 5 years after the BP Oil Spill, families calling for “hugs not walls” on the US/Mexico Border, families living without sanitation services in Lowndes County, AL, people without healthcare fighting for universal healthcare in Vermont, Pennsylvania, and Maine, low wage workers who are struggling to pay their bills while the minimum wage is far from a living wage, vets who come back from fighting unjust wars and continue to struggle to provide for their families, and indeed millions of people who face poverty in its many cruel forms across this country every day. Many of these leaders are inspired by their faith traditions and their understanding of the thinking and theology of Rev. Dr. King to make these fights in the first place.

At the center of both Christ and King’s ministries and missions is a radical critique of social, political and economic systems. For both, they assert that the poor and dispossessed are called to stand against violence, discrimination and poverty, work to build love and community, and to do justice rather than charity. They both assert we can end poverty and that it is God’s will that we do so.

As we mark the 50th anniversary of Rev. Dr. King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech, we must read Matthew 26:11, “the poor will always be with you.” Jim Wallis calls this the most famous Bible verse on poverty. The verse echoes Deuteronomy 15 and calls for radical economic distribution as central for community prosperity. I hear echoes of this verse when I read Dr. King’s statement on true compassion. Indeed, this may well be Rev. Dr. King’s own interpretation of Matthew 26:11:

A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. On the one hand, we are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside, but that will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho Road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life’s highway. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.

The Last Week of Jesus Christ and the Last Year of Martin Luther King

Kairos Center Bible Study Series