This is the third chapter of a forthcoming book from the Kairos Center, on the call for and the work of organizing the new Poor People’s Campaign. Each chapter is accompanied by the edited transcript of a discussion about its key themes by leaders in poor people’s struggles from around the country. Click here to view the other chapters.

The dispossessed of this nation — the poor, both white and Negro — live in a cruelly unjust society. They must organize a revolution against that injustice, not against the lives of the persons who are their fellow citizens, but against the structures through which society is refusing to take means which have been called for, and which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty.

The only real revolutionary, people say, is a man who has nothing to lose. There are millions of poor people in this country who have very little, or even nothing, to lose. If they can be helped to take action together, they will do so with a freedom and a power that will be a new and unsettling force in our complacent national life.

Rev. Dr. King wrote these words for a series of lectures he gave in December of 1967. The passage is one of the clearest statements of how he saw America’s political and economic situation at that time; as well as the vision and strategy behind his call for a Poor People’s Campaign. Looking closely at it can help us understand that vision and strategy, especially the idea that the poor — as a united social force — can and must lead the rest of our society.

That idea is more true today than ever. The current technological revolution is transforming every part of the economy all over the world. Because of our “cruelly unjust” class-based society, this revolution is bringing more poverty and violence instead of shared wealth. The poor are feeling the effects first: they’re becoming totally unnecessary, from the perspective of those who own and control the economy. This puts them in position to lead the “middle class” to political independence and clarity, as they face the trauma and fear of downward mobility.

“The dispossessed of this nation, the poor, both white and Negro, live in a cruelly unjust society…”

Rev. Dr. King didn’t envision the Poor People’s Campaign as a charitable crusade. It wasn’t a campaign for the poor. It was a campaign of the poor to awaken a broad mass movement to abolish poverty and transform the whole of society.

The middle layers of society are the social base of the political power structure. They uphold and protect the cruelly unjust economic system that by its very nature produces poverty. They serve as the “officer corps” of the major institutions of power and influence such as the military, criminal justice and education systems, mass media, and the civic bureaucracy at all levels of government.

The current chronic economic crisis is casting whole sections of these middle layers down into the ranks of the poor and dispossessed. Because of the important role they’ve played for the power structure, this is a threat to the entire global capitalist economic and political system. It’s a time of instability, and this downwardly-mobile middle could be kept on the side of the existing Powers That Be to stabilize the system, or they could move closer to the emerging struggles of the poor and dispossessed to revolutionize the system. The side they take will determine whether or not poverty is abolished and society is transformed.

Politicians in both major parties fight over who’s really representing the interests of the “middle class” and whose policies are going to “rebuild” it. Both parties, along with other religious and ideological leaders, work on behalf of the rich and powerful to keep the critical mass of the middle from going over to the poor and dispossessed.

On the other side, the poor — through their unity and organization — can win large sections of the middle. This is because most of them are as dispossessed as the poor. They too have no ownership or control over the economy or any security over their livelihood and life. Many in families with middle incomes have once in their lifetime experienced poverty and likely will again in the future. Many are just one paycheck or healthcare crisis away from the plight of the poor and homeless. They’re feeling increasingly insecure about their children’s future.

This is the major strategic significance we see in Rev. Dr. King’s idea for the Poor People’s Campaign. He saw that the poor could lead the rest of the nation through a much-needed “revolution of values,” but only if they could unite across color lines and all other lines of division. He took up the task with deep commitment and clarity:

I choose to identify with the underprivileged. I choose to identify with the poor. I choose to give my life for the hungry. I choose to give my life for those who have been left out … This is the way I’m going. If it means suffering a little bit, I’m going that way … If it means dying for them, I’m going that way.

This goes directly against all the anti-poor propaganda that the American people have been subjected to for decades, which maintains that a poor person can only be either a criminal case or a charity case. The poor can be blamed and shamed or they can be pitied. But no one, particularly from middle class, should choose to identify as poor.

In describing the poor, Rev. Dr. King went out of his way to highlight the fact that poverty crosses racial lines. The poor are “both white and Negro.” Poor Latinos, Asians, and American Indians also played leading roles in the Poor People’s Campaign as it came together. There are people today who claim that “white poverty” and “Black poverty” should be thought of as two different conditions. That “poor whites” and “poor people of color” are two fundamentally different groups, who ought to be organized separately. Looking at the reality of America in 1967, Rev. Dr. King opposed that idea.

He was clear about the necessity of the unity of the poor and dispossessed. He taught this message in his last speech:

You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery.

He argued that the poor can unite as the poor no matter their different races and ethnicities. Being poor — having to struggle all the time for what you need to survive — was and is a shared experience for people living in a “cruelly unjust society.” The poor of all races have “little or nothing to lose” with the ending of the poverty-producing social system.

The society Rev. Dr. King described wasn’t just cruel economically. His criticism here excluded no part of society. Society was and is also “cruelly unjust” legally, politically, religiously and racially. It’s cruel in its treatment of women, children, queer people and trans people and disabled people. Its wars are cruel, as are its courts, prisons, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, mines, pipelines, and borders.

It’s the poor, in all their diversity, who deal with the worst of that cruelty and injustice, in all its diversity. Uniting the poor, “both white and Negro,” means uniting against all of this cruelty to strike at its roots.

“They must organize a revolution against that injustice, not against the lives of the persons who are their fellow citizens, but against the structures through which the society has refused to take measures which have been called for, and which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty…”

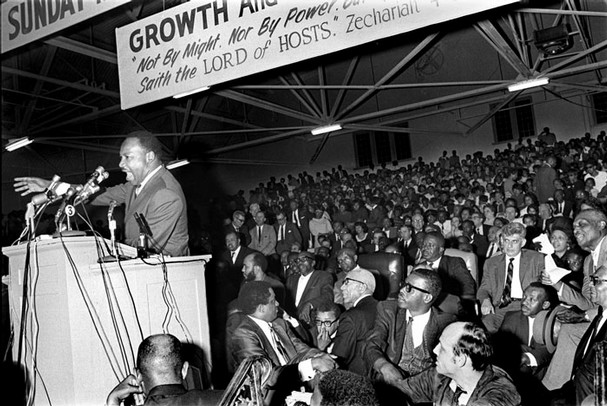

Earlier in 1967, in a speech to the SCLC staff at their annual retreat in Frogmore, South Carolina, Rev. Dr. King said that the time had come to move from a “reform movement” to a “revolutionary movement.” He added: “there must be a radical redistribution of economic and political power.”

Here, he takes that idea a step further by specifying that it’s the poor who must organize that revolution. The idea that the poor can organize or lead anything, let alone a revolution, goes against everything society says about poor people, and everything that poor people are taught about themselves. But it’s the position that Rev. Dr. King took, and an idea he chose to devote his life to.

He makes it clear as well that this revolution can’t focus on getting rid of individuals — not just particular rich people, parties, or politicians — but “structures.” It has to go beyond elections and policies to deeper truths about how decisions are made for our society. It has to get to the question of power, and how to put it in the hands of the poor.

In particular, the revolution that Rev. Dr. King was calling for has to attack the structures that refuse “to take measures … which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty.” In 1967, Rev. Dr. King was arguing that it was possible, given the enormous productivity of the economy, to abolish poverty. It’s even more true today, when the ability of the global economy to produce has grown and continues to grow by leaps and bounds. Poverty is not a problem of scarcity, but of abandonment in the midst of abundance.

This revolution, organized and led by the united poor, is about dealing with that contradiction: on the one hand, the technical possibility of ending poverty; and on the other, the stubborn refusal of the rich and powerful as a ruling class to have that possibility turned into a reality.

“The only real revolutionary, people say, is a man who has nothing to lose. There are millions of poor people in this country who have very little, or even nothing, to lose.”

Rev. Dr. King didn’t make his commitment to the leadership of the poor at random. It wasn’t a purely moralistic decision either. Seeing the cruel injustice of the current structures, seeing the pressing need not just for reform but for a thorough revolution, he had no illusions about the difficulties ahead in carrying it out. The opposition would be fierce and violent. He had already seen this himself in the condemnations and dismissals that came his way after announcing his opposition to the war in Vietnam, when he called the U.S. government the “greatest purveyor of violence” around the world.

History has shown that the Powers That Be will by no means allow for the political unity of those on bottom of the economic ladder. They have used and will continue to use any and every means to discredit, silence, imprison and assassinate anyone who attempts, as Rev. Dr. King did, to help “the poor to take action together.”

Only the poor — those who really have “little or nothing to lose” — could lead that kind of life-or-death fight through to its finish. The Poor People’s Campaign strategy, based on the leadership of the poor, was a necessary departure from the civil rights coalition of poor and middle class Black people and some middle class and wealthy white liberals.

Myths like American Exceptionalism, white supremacy and male superiority have many of us, including many poor people, falsely believing that we have something to lose with the abolition of this inhumane poverty-producing system, when in fact getting rid of this system opens the way for everyone to have everything to gain. At the end of the day, however, the economic and social position of the poor and dispossessed is such that the existing structures don’t promise to let any of us — no matter our color, nationality, or gender — keep what little we have, and certainly don’t have anything better in store for us.

Their class position means that the poor have the least stake, objectively, in the status quo. And their current poverty anticipates the impoverishment that is engulfing and threatening increasing sections of the masses of people, especially those in the so-called middle class who are dispossessed of any ownership and control of the economy. Because of this, the poor can and must lead the middle class and others into a clearer understanding of the causes of and solutions to their problems.

“If they can be helped to take action together, they will do so with a freedom and a power that will be a new and unsettling force in our complacent national life.”

On the other hand, this leadership isn’t automatic or mechanical. Just because the poor are, objectively, positioned as the leading revolutionary force in society, doesn’t mean that they will inevitably step into that role.

For Rev. Dr. King the main requirement for the poor to lead was for them to unite. He pointed out that if the poor could “be helped to take action together” they would do so with “a freedom and a power” capable of unsettling the complacency of the masses of the people including large sections of the middle strata. Through becoming a social and political force united and organized across racial and other lines, the poor can move to the forefront of a broad movement for the emancipation and betterment of all humanity.

Given all the ways that poor and dispossessed in America are shamed and locked up, isolated and divided, united action is as difficult to achieve as it is necessary. Exactly because the “cruelly unjust” nature of our society shows itself in such diverse ways, it takes real ideological effort to expose the connections between injustices: their shared roots in the “structures” of wealth and power that Rev. Dr. King referenced. Achieving this necessary unity and leadership of the poor requires the identification, education and training of many leaders with clarity, competence and commitment like that of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Discussion Questions

- What in your experience has demonstrated the necessity of the leadership of the poor as a social force?

- What forms of organizing have you found most effective in exposing the shared roots of the injustices against which we organize?

- What forms of organizing have you found most effective in building clarity, competence and commitment of leaders?

- What are the barriers and opponents to these forms of organizing?

- What lessons do you take from King’s strategic vision for the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968?

Respondents

Savina Martin, Massachusetts Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival

Kristin Colangelo, University of the Poor

Nicholas Laccetti, Kairos Center for Religions, Rights and Social Justice

Tim Shenk, Committee on US-Latin American Relations

Hy Thurman, Young Patriots Organization

Tim: I had a chance to talk through this article on Friday with several of my students and a couple of CUSLAR alumni, and we gravitated toward the challenge of really needing to define “poor” first before we could figure out what “the leadership of the poor as a social force” means. Willie and Dan’s article offers a roadmap for understanding poor in a much broader way and in a much broader context than we’re usually given. One thing that came out was the reality that we can become poor at any moment, even if we don’t currently consider ourselves poor. The downwardly mobile middle class was a really helpful way for people to understand who we’re talking about.

Nic: I was also struck by the discussion of the middle class. In terms of the question of the necessity of the leadership of the poor, I appreciated how the piece spoke about how the middle class is really up for grabs. It can move in a direction where they continue to reinforce the Powers That Be or move towards the struggles of the poor. Where they go depends on whether the poor as a leading force is able to help that mass of people see their future and interests. I found the line about the middle class being the officer corps of the various structures in our society really striking.

Kristin: One of the things that I think we talked about recently around the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival’s (PPC:NCMR) larger events in cities and small towns is that they bring a lot of people in together around common issues, especially focusing on this question of the leadership of the poor, and breaking myths about the poor. But this then leaves us with the question of what to do after these big events when everyone’s still excited. In our experience we’ve found this to be a very crucial part of organizing that’s really powerful in bringing people together and having these impactful, smaller conversations; whether it’s going to a home or a community center, and really staying in touch with them. This process is what we’ve come to call “panning for gold,” in that we identify leaders from these events for further leadership development efforts. It builds our ground movement and connects existing and potential leaders to the crucial political educational process.

There are many stories from the Homeless Union, Kensington Welfare Rights Union, and Poverty Initiative of people coming together that were previously deeply ideologically divided. One example from KWRU involves white supremacists being changed by coming together with Puerto Rican mothers in a tent city. At first these two groups wouldn’t even look at each other or share space, much less learn and organize together. But then within a little while and with a shared analysis, they came together and organized around what they had in common and were both struggling against. There are many really powerful stories of using events to bring groups together that are currently divided, panning for gold within those groups, using political education strategies to build a collective analysis, and through this process building our movement to end poverty, the broad movement of the poor across all lines of division.

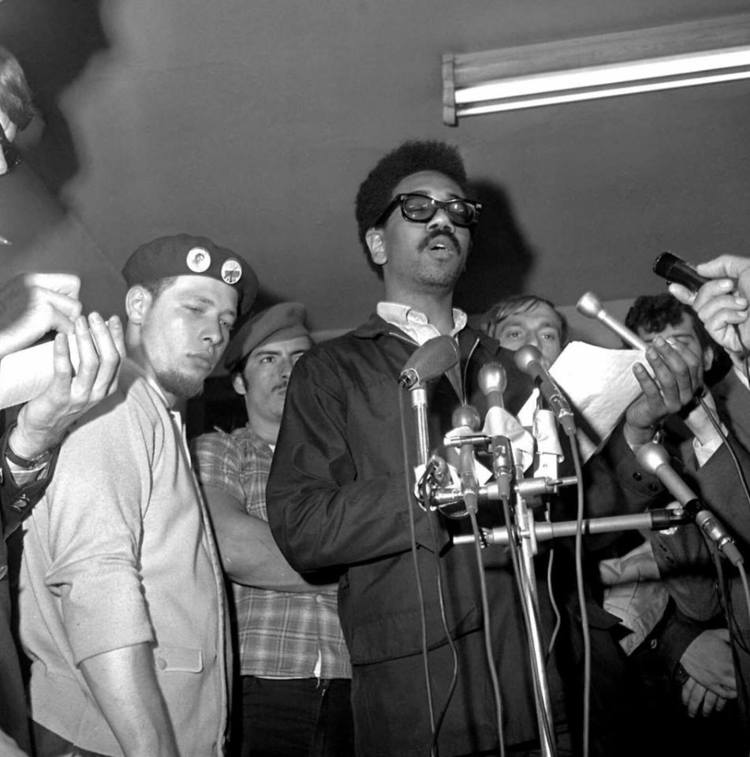

Hy: In Chicago at the end of the 1960s we were each organizing in our communities. I was in the Young Patriots, and we took from Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) the direction that white people needed to go and organize white people. But then the original Rainbow Coalition in Chicago was a way of coming together to organize. It was a coalition that actually belonged to everybody. Most people think that the Black Panther Party or Fred Hampton were the only leaders. But each organization had the same amount of input into it. We would all come together to work around a specific problem. So for example, say the Young Lords identified a problem in the Hispanic community, the Black Panthers and the Young Patriots would come in, actually become one of them and take directions from them as to what they wanted us to do, including assignments like running security.

This was very important. And what it made possible is that we could organize across racial lines and at the same time we could go back to our community and organize our own. I think that was what made the Rainbow Coalition dangerous. Our coming together was a threat to power. But being that threat was probably the downfall of the Rainbow Coalition. We were attacked and we weren’t ready for how strongly and effectively they attacked us. So I think that model is something that’s very much needed today, but we also have to be better prepared for the response.

Savina: In my experience the impact of Dr. King’s assassination in 1968 — followed by riots — left my community blighted and vulnerable. It left an indelible mark on my mind. It also left Spirit to take action rather than sit in silence and suffer. Many years later I joined the National Union of the Homeless which was organized by former and current homeless men, women and families. I clearly recall how we understood the social forces we were up against. We organized ourselves, and we were angry in the right direction to fight for dignity and fairness. We led campaigns and carried them out in over twenty U.S. cities. These forms of organizing turned into taking back what was ours, whether it was abandoned property take-overs, sit-ins or erecting tent cities. We did what we had to do. This effort further confirmed for me the need for deep-rooted organizing among the poor and dispossessed of this nation. In the Union of the Homeless, we always chanted that we were “homeless, NOT helpless!”

Tim: I think the study of history is important for understanding how revolutionary movements across history have actually had the poor and dispossessed as the driving force of transformation. I’ve taken a lot of strength from studying the Haitian Revolution. Frederick Douglass said that the abolition movement “owed incomparably more to Haiti” than to any of the great abolitionists in the U.S., because the Haitians showed the world it was possible for Black enslaved people to defeat the ruling class, but not only that, for a formerly dispossessed class of people to govern themselves. When I hear King’s reference to Pharaoh’s court and what happens when the slaves get together, I think of how in the case of the Haitian Revolution, enslaved people were able to get organized and lead the first and only successful slave rebellion in the Americas.

The first thing they did was abolish slavery, which was an economic system that required working people literally to death for the profit of a few. So abolishing slavery was a huge threat to the colonial powers. The elites of the day couldn’t allow for that narrative to be what won the day. And so after the revolution was successful, and even supported in some moments by the English and the Americans, Haiti was basically strangled by all of the colonial powers that had to make sure that revolution didn’t spread, and Haiti’s impoverishment has been imposed on them these last 200 years.

But there are many lessons from that history that are instructive for today. Saint-Domingue was the crown jewel of the French colonies for two centuries, with a huge amount of money, power and control at stake. What the slaves and mulattoes were able to do was to take the moral narrative of equality and fraternity that was so inspiring to French society, and adapt it for their own situation. They were able to challenge the false unity of poor whites with wealthy whites. They were also able to play the colonial powers against each other. France was at war with England, and the Black revolutionaries used that moment to strike for their independence.

It’s also instructive that on the other side, the colonial elites were willing to try everything to divide the classes of dispossessed and enslaved people, including bribing both poor whites and black generals onto their side and giving mixed-race people more rights for a time in the hope that they wouldn’t join the rebellion. They also told the French soldiers — most of them poor people who were just getting their own independence from the French monarchy — that they were going to be fighting for freedom in this war in the colonies. But when the French soldiers got to Haiti many of them started to realize how they had been lied to. Some of them mutinied or refused to fight.

Eventually, all of the French ruling class measures failed, and their general, Leclerc, called for a war of extermination. He thought it would be easier to kill all of the Black people on the island and bring new slaves from Africa who knew nothing about equality. These are the lengths of brutality the ruling classes have historically been willing to go to, to protect their profits and power. So the success of the Haitian Revolution is an example of the poor and dispossessed being out front and driving the question of how the collective wealth of a society is going to be distributed. Will there be an abolition of slavery? Will there be equality in terms of how socially produced wealth is distributed, or will a few people still be allowed to keep everything and impoverish and enslave the rest of the people?

Nic: PPC:NCMR Theomusicologist Yara Allen has a really great line she uses when she’s asking people to stand to sing together: “We stand together because we stand together.” It took me a minute to really understand the depth of that, but it points to some of the vision behind using mass meetings and moral fusion direct actions as tools to build a broader movement that doesn’t stop after those moments are over. Working together or standing together in those moments allows us to build a foundation for our future long-haul work. We can’t start only with abstract ideas and expect leaders and organization to emerge. We have to start by doing things together. It’s been a powerful experience to be part of that attempt to actually bring people together by taking action together. And that starts to build that commitment and connectedness we need for a broader movement, and also some of that clarity and competence. You can’t really say different injustices are connected without first showing people everybody that’s in struggle around them. And that happens by standing up together first. Yara says this in the context of arts and culture, which plays an important part in encouraging the participation that starts to establish the connectedness a movement needs.

Tim: In addition to concrete things we’re doing together, it’s really powerful to have a big vision from early on about what needs to change. I spent five years in the Dominican Republic learning from and working with organizers and mentors, particularly Angel Pichardo and Lucero Quiroga, as part of an organization called Justicia Global (Global Justice). We had a lot of different fronts open at the same time. We were working with women’s groups, student groups, peasant groups out in the country, and young people in the cities. The leadership there always tried to make it clear that our interests and the issues we were working on were interconnected.

Part of the organizing model allowed for including people like me who weren’t from the DR originally but agreed with the organizational principles, which showed implicitly that the organization understood the need to build an internationalist movement. The issues themselves were almost secondary for what we were trying to build. We had a “socioeconomic and cultural development school” that was a space for political formation. We wouldn’t go too long in our issue-based work before coming together and studying the bigger structures that we were taking on, moving back and forth from the on-the-ground work to theoretical work. We needed to figure out why it was important for rural and urban to get together, young people and adults to get together, students and people fighting exploitative mines — for all of these groups to get to know each other and show up for each other. There was a real conscious effort on the part of our leaders to continually make those connections and to have the big victories be about our development as leaders. Issue-based victories come and go, but the knowledge and experience of our people are key for us in building toward the next struggles. We wouldn’t always be successful on a certain campaign or another, but the actual building of relationships across sectors and identities developed a core of people that became committed to each other and our shared vision.

Savina: In retrospect one of the most important lessons for today that stems from the experience of the National Union of the Homeless is that we did not continue ongoing collectives of study. Today, we realize the importance of not only identifying cadre from the rank-and-file of the poor, but also having a classroom in place for critical thinking, new ideas, and building power. Theory and analysis must go hand in hand with the practical work. Building clarity, competence and having committed core groups is a great first step. But we should avoid the barrier of being too busy to study. Reflecting on how we carry out an action is key to the power of study and analysis.

Another key lesson for today is the importance of replicating leaders. If we are to build an army, we need many generals for the various components of fronts connected to the struggles of workers. We must study the sophisticated forces we are up against. Working in the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is critical for our continued effort to identify leaders, teach, study and build. Utilizing King’s vision of the past to unite the poor and linking systems of oppression to the evils he spoke of during his 1967 speech is a powerful tool to use.

Nic: Willie and Dan point out the significance of King deciding to identify with the poor when so much in our culture goes against that. In particular the middle class is told not to choose to identify as poor. And now there is this narrative that the reactionaries in our current political climate are all poor whites. And that’s not really true even in terms of Trump’s base. But the notion that King actually identified in a really radical way with the poor of all races and all genders was a radical act for his time and for ours. Today there’s a really strong drive to divide the poor from the rest of society and to place blame on them for our current conditions, blaming poor whites for some things and poor people of color for others. So even though it was 50 years ago, it’s still radical, especially in terms of moving those middle segments of society toward the struggles of the poor rather than keeping them aligned with the powers that be.

Tim: When I was talking about this chapter with my students, we were so struck by the passages from Dr. King. It seemed to us like a significant pivot to go from speaking about civil rights, then to include a critique of war and the war economy through the “Beyond Vietnam” speech, and then the leap toward the focus on the poor and dispossessed of every color. King didn’t just do this in theory, but he was at the forefront of getting a wide range of leaders together leading up to the actions in Washington, D.C. in 1968. We can’t underestimate the significance of that, and it seems to be really useful today. So many of us are surprised in a good way about how through the PPC:NCMR, Dr. King’s strategy is resonating across this country right now. People are finding it so relevant, maybe more than ever.

Hy: I was part of the Poor People’s Campaign and lived in Resurrection City in 1968. The vision of Dr. King at that time is something that’s still universal today. We still have a lot of the same problems that we had then. But it was because of King’s vision and because of his plans that I became an organizer. I learned lessons from the techniques of organizing from that experience, along with the resiliency of just never giving up.

Willie: I mean this to me is a pivotal piece, because like Hy, for me, what King died for in the last years of his life is why I’m in this movement. King was assassinated to preempt his attempt to unite the poor. The political police understood that, and the Powers That Be in U.S. history have always done everything they can to prevent the uniting of the bottom. You can have blacks united with blacks, whites united with whites, and women united with women, but only if they remain apart from each other. You do not unite the bottom. And so when Resurrection City came down, it was the end of that effort to unite the poor. The leaders of the SCLC went back to how they had been organizing before and went on to elected and appointed positions of power. But there have been those of us like Hy who have stayed committed. The purpose of the assassination was to preempt the new and unsettling force from impacting other sections of society. And to a large extent we have been cut off from those words and that vision, but there have been those who have carried forward over the fifty years that possibility. Where that happens the use of King’s words and vision continue to be powerful, and the PPC:NCMR is trying to make this dream come true: the unity of the poor across color lines and other lines of division.

Tim: Listening to this conversation about history is really different than what you hear in a lot of classrooms. It’s not about names and dates and times, it’s about trying to develop a strategy based on lessons that we can draw from, both victories and defeats. I want to hold up this question about history and the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968 being rife with potential lessons that can inform our strategy, about how to move forward today.

Willie: The leadership of the poor is not just about those poor people we feel sorry for. Since the assassination of King they’ve tried to say that his attitude toward poverty was as a charity case, that helping the poor is about fixing the poor and not fixing the system. But King was talking about changing the system, because the system is the problem.